Marcella

(b. circa 325, Rome, Italy; d. 410, Rome, Italy)

Marcella was a Roman noble woman who was canonized, or declared a saint, by the Vatican for her role in founding the Christian monastic system. Monasticism dates back to Marcella’s time and is practiced today as a system in which religious devotees renounce their worldly possessions and declare their lives to God. They live together in monasteries under strict religious rules that vary according to the sect.

Marcella was married at a young age, following the death of her father. She was subsequently widowed in the seventh month of her marriage. Rather than remarry, as was custom in Roman society, she declared celibacy, devoting her life to God and the study of the Bible. She owned a palace on Aventine Hill, one of the seven hills that would make up the site where Rome was built, which she turned into a refuge for other noble women wishing to devote their lives to Christianity. The women followed the model of the ascetic monks by renouncing worldly pleasures such as lavish meals, material possessions, and sexual pleasure, to attain spiritual goals.

Marcella’s piety and the reputation of her Christian refuge prompted the formation of several other similar groups in Rome, which began the Roman monastic movement. Marcella ran her informal convent until the year 410, when the Goths invaded Rome. Soldiers ransacked her palace searching for the treasure Marcella was rumored to have. Though she had given away all of her fortunes to the poor, the soldiers beat her to learn the hiding place of her wealth. She managed to escape, but she died from the injuries soon after, in the arms of her favorite pupil, Principia.

During her lifetime, Marcella had a close relationship with Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus, more commonly known as Saint Jerome, who is known for his translation of the Bible from Greek and Hebrew into Latin. Marcella often engaged him in theological debates, documented in their correspondence from the late fourth and early fifth centuries. Most of what we know about Marcella is from the letters of Saint Jerome, most famously his letter 127 to Principia. It was written on the occasion of Marcella’s death, paying tribute to her life and consoling her beloved student. In it, he says the following about his relationship with Marcella:

As in those days my name was held in some renown as that of a student of the Scriptures, she never came to see me without asking me some questions about them, nor would she rest content at once, but on the contrary would dispute them; this, however, was not for the sake of argument, but to learn by questioning the answers to such objections might, as she saw, be raised. How much virtue and intellect, how much holiness and purity I found in her I am afraid to say, both lest I may exceed the bounds of men’s belief and lest I may increase your sorrow by reminding you of the blessings you have lost. This only will I say, that whatever I had gathered together by long study, and by constant meditation made part of my nature, she tasted, she learned and made her own. (Rebenich, Jerome, 125)

When most sources acknowledge the relationship between Marcella and St. Jerome, they inaccurately name her as his pupil rather than his colleague. We know from the letters between them that she often questioned his arguments and was never afraid to criticize him, treating him as an equal student under God.

Despite her contributions to the founding of the monastic system, Marcella remains one of the lesser-known saints of the Roman Catholic Church. She is remembered each year on her saint’s day, January thirty-first.

Marcella at The Dinner Party

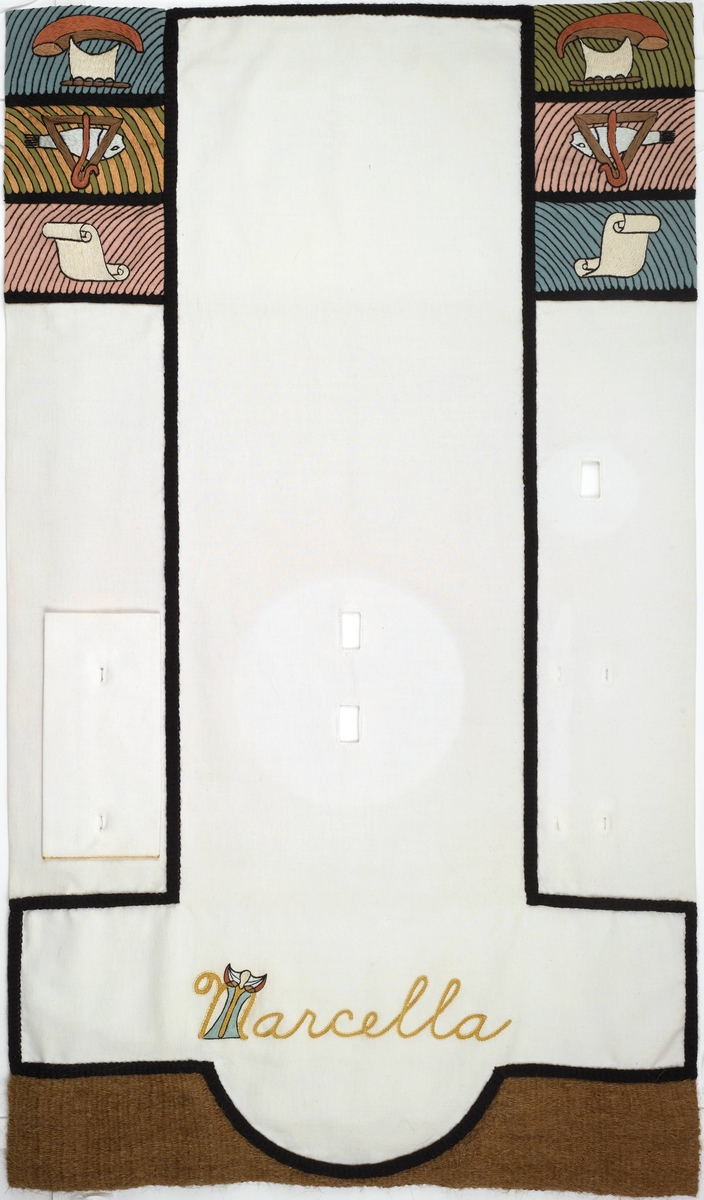

Marcella’s place setting is decorated with the symbols of her sainthood and those of the Christian church. On the runner is an outline of the architectural plan for early Christian basilicas. Marcella’s plate rests on this plan, locating her as an important figure in the early organization of Christianity, central to its development. The front edge of the runner is made of woven camel hairs, also used to make shirts worn by early Christians like Marcella and members of the ascetic women’s convent she founded. These shirts, whose rough fibers irritated the skin, were worn under clothes in an act of penance.

Another important symbol on the front of the runner, located in the first initial of Marcella’s name, is the figure of a woman praying in orans posture—her arms spread out and reaching upward. According to Chicago, the gesture was first associated with goddess figures, and was later used to depict Christian women and then Christ himself. It is used in the place setting to show how early pre-Christian symbols were often co-opted by the church for their own iconography (Chicago, Embroidering Our Heritage, 107).

The back of the runner contains other symbols important to the early church and to Marcella’s life. The scroll symbolizes learning, an important part of convents, as they were often the only sites of education for women in early society. Below the scroll is a composite image of a fish, staff, and triangle. The triangle was an early symbol of female genitalia, which became a symbol of the goddess and the sacred feminine, but in Christianity it also represents the Holy Trinity of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

The triangle encompasses the staff, a symbol of Christ as the “Good Shepherd”; it also symbolizes the leadership and authority conferred on bishops. The fish, another early symbol of the church, was used by Christians as a secret means of denoting their faith under fear of persecution; the Greek letters that spell out the word “fish,” also start each of the words “Jesus Christ, God’s Son, Savior.”

These symbols identify Marcella as a “savior of women” during the early Christian period, comparable to Christ (Chicago, Embroidering Our Heritage, 109). The ship, also appears on the back of the runner, is another important symbol of early Christianity, representing the Christian church sailing through the “perilous waters” of all that is not Christian; its presence links Marcella’s life, including all of the peril she faced, with the development of the church and Christian monasteries.

Primary Sources

Correspondence of Saint Jerome, d. 419 or 420. Fifth century.

Translations, Editions, and Secondary Sources

Butler, Alban. Butler’s Lives of the Saints. 12 vols. Ed. David Hugh Farmer and Paul Burns. New full ed., Tunbridge Wells, UK: Burns & Oates and Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1995–2000.

Kraemer, Ross S., ed. Maenads, Martyrs, Matrons, Monastics: A Sourcebook on Women’s Religions in the Greco-Roman World. 1988; rev. ed., Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Mierow, Charles Christopher, trans. The Letters of St. Jerome. Introduction and notes by Thomas Comerford Lawler. Westminster, Md.: Newman Press, 1963.

Rebenich, Stefan. Jerome. London: Routledge, 2002.

Wright, F. A., trans. Jerome: Select Letters. 1933; reprint ed., Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Marcella place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

Place Setting Images

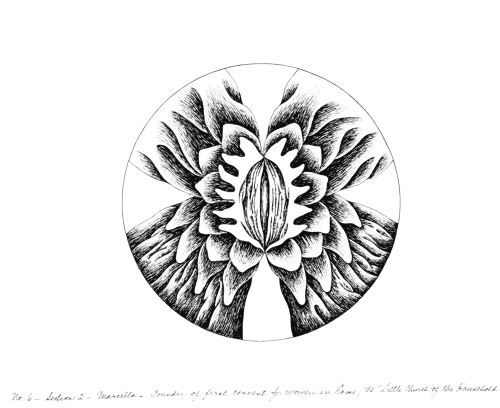

Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Marcella plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint) and rainbow luster overglaze, 14 × 14 × 1 in. (35.6 × 35.6 × 2.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Marcella runner), 1974–79. Cotton/linen base fabric, woven interface support material (horsehair, wool, and linen), cotton twill tape, silk, synthetic gold cord, wool, camel hair, wool fabric, silk thread, 51 1/2 × 29 7/8 in. (130.8 × 75.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago

Biographical Images

Related Heritage Floor Entries

Web Resources

Christian Classics Ethereal Library—the Church Fathers: St. Jerome’s correspondence

Catholic Online : Saint Marcella

The Holy Shrine of Saint Marcella