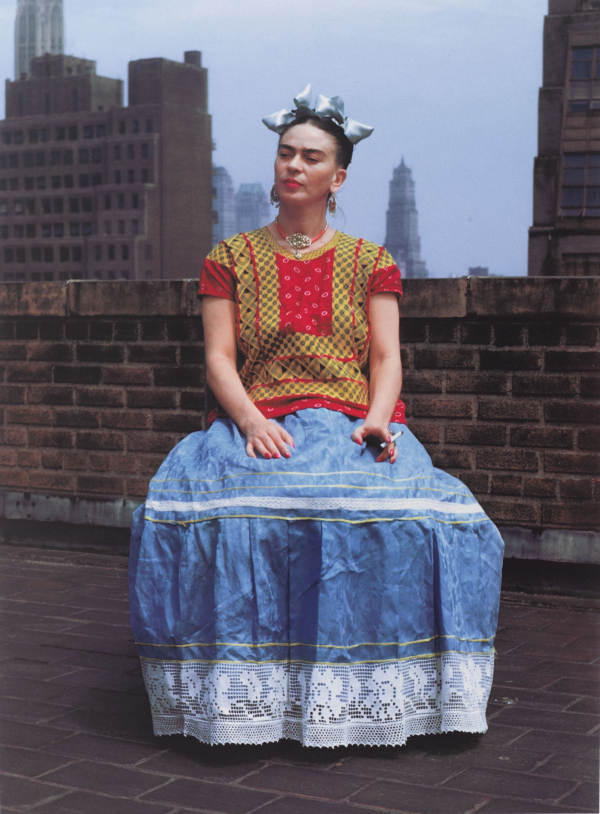

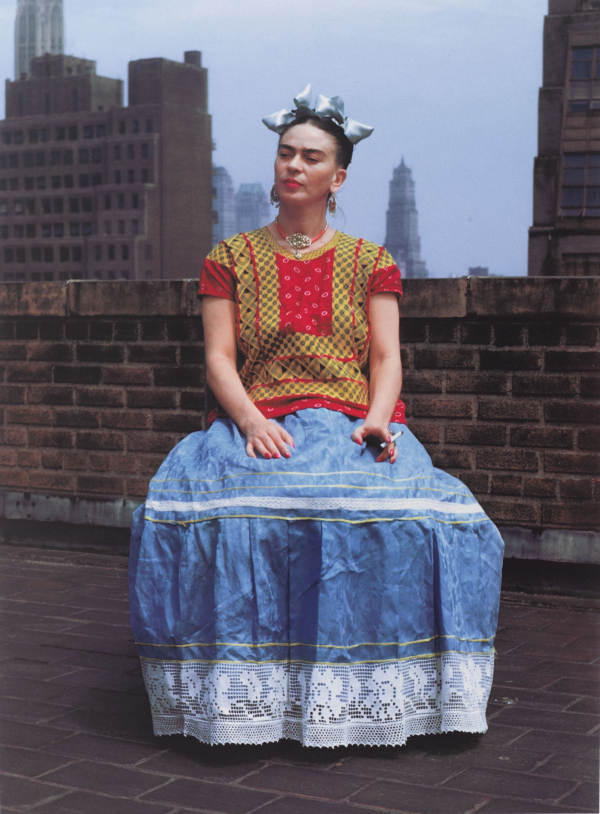

Nickolas Muray (American, born Hungary, 1892–1965). Frida in New York, 1946; printed 2006. Carbon pigment print, image: 14 x 11 in. (35.6 x 27.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum; Emily Winthrop Miles Fund, 2010.80. © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

Nickolas Muray (American, born Hungary, 1892–1965). Frida in New York, 1946; printed 2006. Carbon pigment print, image: 14 x 11 in. (35.6 x 27.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum; Emily Winthrop Miles Fund, 2010.80. © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954). Appearances Can Be Deceiving, n.d. Charcoal and colored pencil on paper, 111/4 x 8 in. (29 x 20.8 cm). Collection of Museo Frida Kahlo. © 2019 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Kahlo used her Tehuana costume to express her radical politics and artistic sensibilities. Her specific sartorial choices were also designed to hide her limp and the medical corsets used to support her deteriorating spine. She underscores her visual message in her own words: “Appearances can be deceiving.” The corset she drew is on display.

Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954). Self-Portrait with Braid, 1941. Oil on hardboard, 20 x 151/4 in. (51 x 38.5 cm). The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and the Vergel Foundation. © 2019 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Kahlo painted this work shortly after she cut her hair, as seen in Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (1940). Her pretzel-shaped, beribboned braid cannot restrain the strands of unruly hair. Seemingly nude, Kahlo is both protected and threatened by serrated leaves called “lion’s teeth.” Her necklace is similar to the choker seen in several photographs, but Kahlo added two distinctive beads: a fertility conch, symbolizing life, and a death mask.

Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954). Self-Portrait as a Tehuana, 1943. Oil on hardboard, 30 x 24 in. (76 x 61 cm). The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and the Vergel Foundation. © 2019 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Kahlo wears a starched resplandor headdress in this self-portrait. The sumptuous flowers in her hair, gold background, and portrait of Diego Rivera on her brow recall the Mexican genre of “Crowned Nun” portraits, which depict nuns taking the veil and becoming betrothed to Jesus.

Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954). Self-Portrait with a Necklace, 1933. Oil on metal, 133/4 x 11 in. (35 x 29 cm). The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and the Vergel Foundation. © 2019 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Kahlo began this self-portrait in Detroit but repainted the necklace, erasing the central stone after her return to New York. The necklace, the lace frill of her blouse, and her beribboned hair contrast with her dark eyebrows and pronounced facial hair, challenging conventional norms of femininity and beauty.

In a photograph accompanying an article in the Detroit News she can be seen painting this self-portrait beneath an extremely condescending headline. When the reporter asked her about Rivera, Kahlo replied: “Of course he does pretty well for a little boy, but it is I who am the big artist.”

Lucienne Bloch (1909–1999), Frida Kahlo at the Barbizon Plaza Hotel, New York, 1933. Black and white photograph, 21 x 17 in. (53.5 x 43.2 cm). The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of the 20th Century Mexican Art and the Vergel Foundation. © Lucienne Allen dba Old Stage Studios. (Image courtesy of Old Stage Studios)

In 1933 Rivera was commissioned to paint a mural for New York’s Rockefeller Center. He was fired for incorporating—and refusing to remove—a prominent portrait of the late communist leader Vladimir Lenin. Lucienne Bloch, Rivera’s assistant and an artist in her own right, documented the unfinished mural before it was destroyed. Bloch became a close friend of Kahlo’s, taking candid photographs of the couple. Self-Portrait with Necklace (1933), included in this exhibition, can be seen on the wall.

Guillermo Kahlo, Frida Kahlo, circa 1926. Silver gelatin print, 63/4 x 43/4 in. (17.2 x 12.2 cm). Collection of Museo Frida Kahlo. © Frida Kahlo & Diego Rivera Archives. Bank of Mexico, Fiduciary in the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museum Trust

Frida Kahlo must have liked this image, a copy of which she gave to Diego Rivera just before their marriage in 1929. In numerous later self-portraits, she would emulate this three-quarter pose, as well as the directness and stillness of gaze that her father so often captured.

Nickolas Muray (American, born Hungary, 1892–1965). Frida on Bench, 1939. Carbon print, 18 x 14 in. (45.5 x 36 cm). Courtesy of Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives

This celebrated image, taken in Nickolas Muray’s New York studio, has a floral backdrop made from a fabric similar to one of Kahlo’s skirts. Kahlo usually preferred to pose in three-quarter view, but here she gazes straight at the camera.

Cotton huipil with machine-embroidered chain stitch; printed cotton skirt with embroidery and holán (ruffle). © Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. (Photo: Javier Hinojosa, courtesy of V&A Publishing)

Many of Kahlo’s clothes were made in the Tehuantepec style by local dressmakers. However, the quality of the floral hand-embroidery on this huipil indicate that it is an authentic piece from Oaxaca.

Kahlo attracted attention when she wore outfits of this type. When Julien Levy took her to the Central Hanover Bank on Fifth Avenue, she was followed by a “flock of children: who asked, ‘Where’s the circus?’”

Cotton Mazatec huipil hand-embroidered and appliquéd; plain floor-length skirt. © Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. (Photo: Javier Hinojosa, courtesy of V&A Publishing)

This long Mazatec huipil is a composite of commercially available elements. It includes bold floral designs worked in cross-stitch, horizontal bands of satin ribbon, and false sleeves edged with pleated frills. It is finished with machine-made lace and rickrack braid.

Kahlo can be seen wearing a similar huipil in a photograph by Leo Matiz.

Revlon nail polishes, before 1954. © Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. (Photo: Javier Hinojosa, courtesy of V&A Publishing)

Kahlo favored the Revlon brand for its matching shades for nails and lips. She preferred reds and dark pinks, often coordinating them with the flowers in her hair.

Plaster corset, painted and decorated by Frida Kahlo, Museo Frida Kahlo. © Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Archives, Banco de México, Fiduciary of the Trust of the Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums. (Photo: Javier Hinojosa, courtesy of V&A Publishing)

The hardened plaster of Kahlo’s corsets had to be cut with surgical pliers to be removed; only the front half of this painted example survives. The circular hole over the abdomen was probably intended to provide ventilation, but it also suggests the absence of a fetus.

Lola Alvarez-Bravo (Mexican, 1907–1993). Frida Kahlo (with dog), circa 1944. Gelatin silver print, 10 x 8 in. (25.2 x 20.3 cm). Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: Lola Alvarez Bravo Archive. © 2019 Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Colima. Dog Figure, 200 B.C.E.–500 C.E. Ceramic, 103/4 x 81/2 x 161/2 in. (27.3 x 21.6 x 41.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum; A. Augustus Healy Fund, 37.390. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

Kahlo loved the Mexican hairless dog breed xoloitzcuintli, named after Xólotl, the Aztec canine god associated with the underworld, such as the one she depicted in the painting The Love Embrace of the Universe, the Earth (Mexico), Diego, Me, and Señor Xólotl (1949). Her passion for the animals extended to a collection of Colima dog sculptures, like the one displayed here.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving

February 8–May 12, 2019

Mexican artist Frida Kahlo’s unique and immediately recognizable style was an integral part of her identity. Kahlo came to define herself through her ethnicity, disability, and politics, all of which were at the heart of her work. Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is the largest U.S. exhibition in ten years devoted to the iconic painter and the first in the United States to display a collection of her clothing and other personal possessions, which were rediscovered and inventoried in 2004 after being locked away since Kahlo’s death, in 1954. They are displayed alongside important paintings, drawings, and photographs from the celebrated Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art, as well as related historical film and ephemera. To highlight the collecting interests of Kahlo and her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, works from our extensive holdings of Mesoamerican art are also included.

Kahlo’s personal artifacts—which range from noteworthy examples of Kahlo’s Tehuana clothing, contemporary and pre-Colonial jewelry, and some of the many hand-painted corsets and prosthetics used by the artist during her lifetime—had been stored in the Casa Azul (Blue House), the longtime Mexico City home of Kahlo and Rivera, who had stipulated that their possessions not be disclosed until 15 years after Rivera’s death. The objects shed new light on how Kahlo crafted her appearance and shaped her personal and public identity to reflect her cultural heritage and political beliefs, while also addressing and incorporating her physical disabilities.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is based on exhibitions at the Frida Kahlo Museum (2012), curated by Circe Henestrosa; and the V&A London (2018), curated by Claire Wilcox and Circe Henestrosa, with Gannit Ankori as curatorial advisor. Their continued participation has been essential to presenting the Brooklyn exhibition, which is organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator for the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, and Lisa Small, Senior Curator, European Art, Brooklyn Museum, in collaboration with the Banco de México Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, and The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is presented by

Leadership support for this exhibition is provided by Bank of America. Major support provided by Delta and Aeromexico. Generous support provided by Peggy Jacobs Bader, Franci Blassberg and Joe Rice, Leach, a Chargeurs company, the Dobkin Family Foundation, Christina and Emmanuel Di Donna, and The Kaleta A. Doolin Foundation.

With special thanks to the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, the Instituto Nacional de Antropologíca e Historia, and the Mexican Cultural Institute of New York.

Preferred Hotel Partner