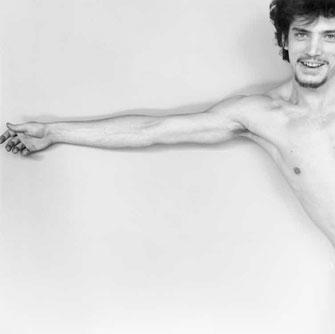

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946–1989). Self Portrait, 1975. Polaroid print. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission

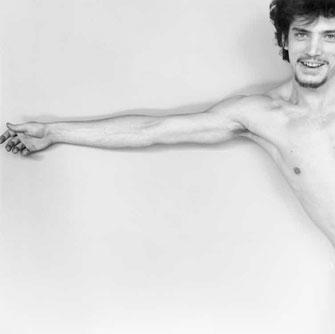

Robert Mapplethorpe (American, 1946–1989). Self Portrait, 1975. Polaroid print. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Frank O’Hara, 1960. Oil on canvas, 333⁄4 x 16 × 1 in. (85.7 × 40.6 × 2.5 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, NPG.96.128; gift of Hartley S. Neel. © Estate of Alice Neel

The American realist Alice Neel captured O’Hara’s distinctive profile, which she described as “a romantic falconlike profile with a bunch of lilacs.” One of the most important poets of postwar America, O’Hara was a leader in making American verse more intimate and personal. His style was direct and immediate, and his topics were generated from his day-to-day encounters with people and places. O’Hara was a curator at the Museum of Modern Art and wrote poetry during his lunch hour; his relaxed, humorous, and offhand style hid the deep seriousness with which he took his art and his subjects. His irony was instead a defensive mechanism, a tendency toward obliqueness that provided cover in a society that was threatening to gay men. O’Hara also kept much of his life hidden from his closest friends, while at the same time he allowed himself to become the subject of many of America’s leading artists.

Félix González-Torres (American, 1957–1996). “Untitled” (Portrait of Ross in L.A.), 1991. Candies individually wrapped in multicolored cellophane, endless supply. Overall dimensions vary with installation, ideal weight: 175 lb. The Art Institute of Chicago; promised gift of Donna and Howard Stone. Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York © The Félix González-Torres Foundation

Even as a minimalist, Félix González-Torres also had a whimsical, humanistic side that showed the influence of pop art on his installations. In this “portrait” of his deceased partner, Ross Laycock, González-Torres created a spill of candies that approximated Ross’s weight (175 lbs.) when he was healthy. Viewers are invited to take away a candy until the mound gradually disappears; it is then replenished, and the cycle of life and death continues. While González-Torres wanted the viewer/participant to partake of the sweetness of his own relationship with Ross, the candy spill also works as an act of communion. More darkly, the steadily diminishing pile of cheerfully wrapped candies shows the dissolution of the gay community, as society ignored the AIDS epidemic. In the moment that the candy dissolves in the viewer’s mouth, the participant also receives a shock of recognition at his or her complicity in Ross’s demise.

Charles Demuth (American, 1883–1935). Dancing Sailors, 1917. Watercolor over graphite on paper, 8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4 cm). Courtesy Demuth Museum, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

While painters such as Marsden Hartley turned to abstraction as a way of sublimating their same-sex desires, Charles Demuth divided his artistic work into two distinct strands. As an artist associated with Alfred Stieglitz’s pathbreaking 291 gallery, Demuth produced works of high modernist abstraction, such as his industrial landscapes of Pennsylvania. Paralleling this work, as a gay man he also produced a series of realistic genre scenes of gay life, albeit not intended for wide circulation. In this picture, Demuth observes sailors who are in New York City on shore leave, a favorite subject of the artist. His scene evokes the world of male relationships and gender-bending that arose in the isolated environment of the navy’s ships.

Berenice Abbott (American, 1898–1991). Janet Flanner, 1927. Gelatin silver print, 91⁄2 x 73⁄8 in. (24.1 × 18.7 cm). Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. © Berenice Abbott/Commerce Graphics, New York

In 1922, Janet Flanner settled in Paris with her lover, Solita Solano. She would spend the next fifty years writing her “Letter from Paris,” a column that appeared regularly in the New Yorker. Flanner and Solano became fixtures in the salon life of the city, their homosexuality providing a crucial entrée into the most fashionable literary groups, which were then dominated by wealthy expatriate lesbians. Flanner signed her column with the decorously French and sexually ambiguous pseudonym “Genêt.” She used “Genêt” to hide her identity, but like most masks, the name revealed as much as it hid. With her campy prose and focus on known gay and lesbian personalities, Flanner provided a knowing glimpse of the Paris “in” crowd. In this portrait by Berenice Abbott, Flanner wears two masks, which—like her pseudonym—suggest her multiple layers.

AA Bronson (Canadian, b. 1946). Felix, June 5, 1994, 1994 (printed 1999). Lacquer on vinyl, 84 × 168 in. (213.4 × 426.7 cm). National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa; Purchased 2001. © AA Bronson, courtesy Esther Schipper Gallery, Berlin

I made this photograph of Felix a few hours after his death. He is arranged to receive visitors, and his favorite objects are gathered about him: his television remote control, his tape-recorder, and his cigarettes. Felix suffered from extreme wasting, and at the time of his death his eyes could not be closed: there was not enough flesh left on the bone. Felix and Jorge and I lived and worked together from 1969 until 1994. During that time we became one organism, one group mind, one nervous system; one set of habits, mannerisms, and preferences. We presented ourselves as a “group” called General Idea, and we pictured ourselves in doctored photographs as the ultimate artwork of our own design: we transformed our borrowed bodies into props, significations manipulated to create an image, a reality.

—AA Bronson

Keith Haring (American, 1958–1990). Unfinished Painting, 1989. Acrylic on canvas, 393⁄8 x 393⁄8 in. (100.0 × 100.0 cm). Courtesy of Katia Perlstein, Brussels, Belgium ©Keith Haring Foundation

In the midst of the AIDS crisis, the poet Thom Gunn said he never thought there was a “‘gay community’ until the thing was vanishing.” In 1990, 18,447 Americans died of AIDS. The artist Keith Haring would be one of them, passing away on February 16, 1990, at the age of thirty-one. Haring had vaulted to public prominence as a graffiti artist whose comical and mysterious cartoons started appearing randomly in New York City’s subway system and led him to mainstream fame in the art world. The sketchy, skittering nature of his drawing is worked into this painting, but the structure of the unfinished work gives it a formal weight. The hanging strings of the unfinished painting suggest not just incompletion but unraveling.

Florine Stettheimer (American, 1871–1944). Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, circa 1925. Oil on canvas, 241⁄4 x 241⁄2 in. (61.6 × 62.2 cm). Gift from the Estate of Ettie and Florine Stettheimer, Michele and Donald D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, Massachusetts. Photography by David Stansbury

In this portrait, Florine Stettheimer presents Marcel Duchamp as an androgynous, disembodied, light-emanating head. From 1915 until 1935, Stettheimer and her sisters hosted a salon for New York’s cultural elite in their flamboyantly decorated Upper East Side apartment—replete with cellophane drapery, rococo furniture, and Florine’s paintings of their guests. The Stettheimers’ salon was a space where sexuality remained fluid, ambiguous, and largely unspoken, yet at the center of social roles. Marcel Duchamp joined the Stettheimers’ milieu in 1917 and remained one of Florine’s most important guests and ardent supporters. “Marcel in real life is pure fantasy,” wrote Henry McBride, art critic and fellow member of the Stettheimers’ circle. “He is his own best creation.”

Thomas Cowperthwaite Eakins (American, 1844–1916). Walt Whitman, 1891 (printed 1979). Platinum print, 41⁄16 x 413⁄16 in. (10.3 × 12.2 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, NPG.79.65

When Walt Whitman first published Leaves of Grass in 1855, he found the source for American vitality in a democracy rooted in the connection between its people and nature. Whitman’s refusal to accept the existence of boundaries and limits on the body, as well as the mind, is the most radical statement ever of American individualism. Expansively omnisexual in his writings, Whitman spent the Civil War years and after with his lover, Peter Doyle, a Confederate deserter. Inspired by the comradeship engendered between men under fire, Whitman celebrated love and affection between men in poems he collected under the titles “Drum Taps” and “Calamus.” Just as society’s attitudes were consolidating into a rigid division that outlawed the homosexual, Whitman’s poetry and his life proclaimed that the possibilities of desire were not so easily characterized and contained.

George Wesley Bellows (American, 1882–1925). Riverfront No.1, 1915. Oil on canvas, 453⁄8 x 631⁄8 in. (115.3 × 160.3 cm). Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio: Howald Fund Purchase 1951.011

Young working-class males, from both the hinterland and abroad, flocked to American cities, seeking jobs, social mobility, and independence from the societies they had left behind. For the urban poor and working classes, the city had few amenities; during the sweltering summer heat, boys and men would throng the docklands to swim in the river and socialize. George Bellows captured these and other scenes of city life in paintings that were both celebrations of urban vitality and indictments of the conditions under which the poor lived. The excess population of young men (and the relative absence of eligible women) encouraged a fluidity in sexual behavior that would not have occurred otherwise. Note the well-dressed dandy watching the bathing youths—very much the odd man out. In this display of male flesh, Bellows was a scrupulous observer of the homosociality of city life as well as its class separations.

HIDE/SEEK: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture

November 18, 2011–February 12, 2012

The first major museum exhibition to focus on themes of gender and sexuality in modern American portraiture, HIDE/SEEK: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture brings together more than one hundred works in a wide range of media, including paintings, photographs, works on paper, film, and installation art. The exhibition charts the underdocumented role that sexual identity has played in the making of modern art, and highlights the contributions of gay and lesbian artists to American art. Beginning in the late nineteenth century with Thomas Eakins’ Realist paintings, HIDE/SEEK traces the often coded narrative of sexual desire in art produced throughout the early modern period and up to the present. The exhibition features pieces by canonical figures in American art—including George Bellows, Marsden Hartley, Alice Neel, and Berenice Abbott—along with works that openly assert gay and lesbian subjects in modern and contemporary art, by artists such as Jess Collins and Tee Corinne.

In addition to revealing connections between sexual identity and formal developments in modern art, HIDE/SEEK presents artists’ responses to the Stonewall Riots of 1969, the AIDS epidemic, and postmodern themes of identity, highlighted with major pieces by artists such as AA Bronson, Félix González-Torres, and Annie Leibovitz. More than simply documenting a prominent subculture often relegated to the margins of American art, HIDE/SEEK offers a unique survey of more than a century of American portraiture and leads the way towards a more nuanced and inclusive understanding of modern art in America.

Some pieces in this exhibition are directed toward adult audiences. Parents and teachers are advised to preview the exhibition.

HIDE/SEEK: Difference and Desire in American Portraiture was originally organized by the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, and has been reorganized by the Brooklyn Museum and the Tacoma Art Museum. The original presentation was co-curated by David C. Ward, National Portrait Gallery, and Jonathan D. Katz, director of the doctoral program in visual studies at the State University of New York at Buffalo. The Brooklyn Museum presentation is coordinated by Tricia Laughlin Bloom, Project Curator.

The Brooklyn presentation is sponsored by

Other generous support has been provided by The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Barbara and Richard Moore, The Calamus Foundation, the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, the May and Samuel Rudin Family Foundation, Inc., Donald A. Capoccia and Tommie Pegues, the Steven A. and Alexandra M. Cohen Foundation, Inc., Leslie and David Puth, Allison Grover and Susie Scher, the David Schwartz Foundation, Mario J. Palumbo, Jr., Tom Healy and Fred Hochberg, Hermes Mallea and Carey Maloney, and other generous donors.

Educational programs are supported by the Keith Haring Foundation.

Print media sponsor