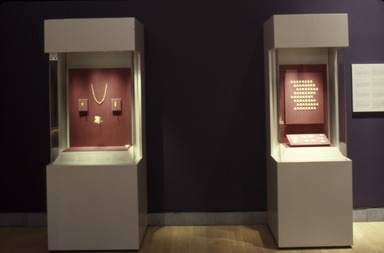

Gold of the Nomads: Scythian Treasures from Ancient Ukraine, October 13, 2000 through January 21, 2001 (Image: ECA_E_2000_Gold_Nomads_001_SL5.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2000)

Gold of the Nomads: Scythian Treasures from Ancient Ukraine, October 13, 2000 through January 21, 2001 (Image: ECA_E_2000_Gold_Nomads_002_SL5.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2000)

Gold of the Nomads: Scythian Treasures from Ancient Ukraine, October 13, 2000 through January 21, 2001 (Image: ECA_E_2000_Gold_Nomads_003_SL5.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2000)

Gold of the Nomads: Scythian Treasures from Ancient Ukraine, October 13, 2000 through January 21, 2001 (Image: ECA_E_2000_Gold_Nomads_004_SL5.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2000)

Gold of the Nomads: Scythian Treasures from Ancient Ukraine, October 13, 2000 through January 21, 2001 (Image: ECA_E_2000_Gold_Nomads_005_SL5.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2000)

Gold of the Nomads: Scythian Treasures from Ancient Ukraine

-

April 1, 2000

The Scythians, a fierce nomadic tribe that flourished more than 2500 years ago in what is present-day Ukraine, are among the most fascinating, but least familiar, of the great warrior cultures that dominated the European steppes for centuries. Although the Huns and Mongols were also known for their ferocity and ruthlessness, the Scythians left a more tangible and artistic legacy through their lavishly provisioned tombs, which preserved one of the most complete material records of any nomadic people.

The Scythians left no written record of their culture, but two rich sources of information about them have survived to this day: the historical writings of Greeks such as Herodotus, and archaeological evidence excavated from Scythian burial sites. Scythian gold artifacts, first unearthed in the 1770s from massive burial mounds known as kurhans, were so extraordinary that the Russian empress Catherine the Great ordered their systematic study, launching what became the field of Scythian archaeology. In the ensuing years exquisite gold pieces, including jewelry, weapons, and ceremonial objects[,] were excavated by Russian and Ukra[i]nian archaelogists from the Scythian burial mounds in the steppes of Ukraine and Russia.

Some of the most extraordinary finds have been made within the last two decades. The most important of these works are featured in Gold of the Nomads: Scythian Treasures from Ancient Ukraine, the largest exhibition organized by Ukraine since its independence in 1991 and the first to be sent to the United States. This presentation has drawn over 170 objects from the Museum of Historical Treasures of Ukraine, The Institute of Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, and the State Historical Archaeological Preserve of Ukraine. In surprising contrast to the belief that the Scythians were savage warriors, modern archaeological work has disclosed that they were among the greatest art patrons of their day. Some of the objects in Scythian burial mounds were clearly made by the Scythians themselves, displaying a sophisticated version of the “animal style” that is associated with the central Asian steppes. Other objects reveal considerable influence from the artistic traditions of ancient Near Eastern cultures. But much of the lavish gold jewelry, vessel work, and weaponry found in the tombs was commissioned by the Scythians from workshops in the Greek settlements along the northern coast of the Black Sea. Many of these gold objects reveal a collaboration between trained, and most likely Greek, metalworkers and less-skilled apprentices who may well have been Scythian.

Although less is known of Scythian women than of men, examination of intact tombs reveals that females wore long, loose robes, in some cases virtually covered with gold plaques. They adorned themselves with gold headdresses, bracelets, rings, earrings, and necklaces. Males wore long tunics, slim trousers, and metal armor sometimes crafted from gold. Their burials, and sometimes those of women, have revealed arsenals of weapons including knives, short swords, richly decorated scabbards, bow-and-quiver cases, shields, helmets, and whips. Royalty and other high-born Scythians were interred along with servants, as well as with containers for cooking and storage.

Greek artists began to adapt their works to Scythian taste and in turn were influenced by Scythian artistic traditions. The Greeks’ intricate metalworking techniques, love of figural narratives, naturalistic detail, and fondness for vegetal ornament became invigorated by the Scythian predilection for depictions of animals, often in fierce combat, and designs that convey swirling, restless movement. The result is a unique style that successfully fuses disparate artistic sensibilities.

Many works in the exhibition illustrate this successful synthesis, among them a remarkable gold bowl bearing in high relief the heads of horses clearly descended from those on the Parthenon frieze. The horse heads form a circle, rotating in a whirling, insistent rhythm that is typical of Scythian artistry.

The Scythians amassed the wealth necessary to finance the creation of their gold works by dominating the trade in grain, furs, and amber to the Black Sea coast and the Greek mainland. By the fourth century B.C., at the height of their power, the Scythians held sway over an area embracing most of modern-day Ukraine and the plains of southern Russia, completely commanding the agricultural communities within their domain. Despite their mastery of this crucial trade crossroads, by the third century B.C. the Scythians had all but disappeared, ousted by invading peoples known as Sarmatians. Scholars believe that several factors may have contributed to the downfall of the Scythians, among them worsening climatic conditions, over-grazing by cattle, and a complacency, resulting from prosperity, that left them unprepared to resist the Sarmatians. These fellow invaders also created superb gold objects, some examples of which are included in the exhibition. The Scythians left behind only the memory of their military prowess and the treasure trove of their extravagant gold artworks.

There are some 40,000 of the massive Scythian burial mounds in Ukraine that remain to be excavated. This is a painstaking process made more difficult by the fact that the Scythians placed their graves from six to forty-five feet below ground level and covered them with up to seventy additional feet of earth. The largest kurhans span more than 300 feet in diameter at their bases.

Brooklyn Museum Archives. Records of the Department of Public Information. Press releases, 1995 - 2003. 2000, 045-47.

View Original