Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_01_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_02_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_03_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_04_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_05_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_06_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_07_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_08_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_09_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_10_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_11_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_12_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_13_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_14_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_15_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_16_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_17_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_18_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_19_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_20_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_21_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_22_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_23_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_24_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_25_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_26_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_27_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_28_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_29_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_30_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_31_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_32_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_33_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_34_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_35_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_36_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_37_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_38_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_39_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_40_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_41_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_42_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_43_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_44_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_45_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_46_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_47_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_48_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_49_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_50_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_51_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_52_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_53_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_54_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_55_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_56_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_57_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_58_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_59_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_60_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_61_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_62_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_63_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art, August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008 (Image: DIG_E2007_Infinite_Island_64_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2007)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art

-

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art presents a diverse, exciting selection of recent work in painting, installation, photography, prints, drawings, video, and sculpture by forty-five established and emerging Caribbean artists. Some of the participating artists live and work in the region, while others have resettled abroad, reflecting the modern Caribbean diaspora to metropolitan centers around the world—including Brooklyn, home to one of the largest Caribbean communities in the United States.

The title Infinite Island, alluding to Columbus’s voyages and the beginnings of colonialism, evokes the contradictions, complexities, and multiple perspectives that characterize the contemporary Caribbean and its presentation in art. According to one account quoted by the curator and critic Gerardo Mosquera, Columbus—hoping he had found the “Indies”—asked the indigenous Indians of Cuba if the land was an island or a continent. The Indians, who envisioned the open seas as corridors and bridges to myriad other islands, replied that it was an infinite land of which no one had seen the end. The phrase “Infinite Island” suggests the tension between containment and expansion, insularity and global interconnections, that continues to define the Caribbean and its geopolitical relations with the rest of the world—a tension that is an animating force in its culture and its art. Eurocentric definitions of the Caribbean are part of the legacy of slavery and colonialism; at the same time, however, the postcolonial mix of cultures, along with the modern diaspora of migration abroad, has created a dynamic, flexible culture that is constantly transforming itself and generating new perspectives.

The exhibition presents four overlapping themes, which run throughout the art on view, as entry points into the complexity of the works: identity and politics; history and memory; myth, religion, and belief; and popular culture. Engaging these themes, the artists confront issues of isolation, migration, and displacement from the Caribbean and explore recent sociopolitical and cultural changes. They challenge existing stereotypes about the region, offering varied perspectives on a continually reimagined Caribbean identity.

Tumelo Mosaka

Associate Curator of Exhibitions -

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art (L’Île infinie: art contemporain des Caraïbes)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art (L’Île infinie: art contemporain des Caraïbes) présente une sélection diverse et captivante d’oeuvres récentes, y compris des oeuvres peintes, des installations, des photos, des gravures, des dessins, des vidéos et des sculptures, exécutées par quarante-cinq artistes nouveaux et établis des Caraïbes. Certains participants vivent et travaillent dans la région, tandis que d’autres sont partis à l’étranger, reflétant la présence de la diaspora caribéenne moderne dans les métropoles du monde entier — notamment à Brooklyn, qui abrite l’une des plus importantes communautés caribéennes des États-Unis.

Le titre « L’Île infinie », qui fait référence aux voyages de Christophe Colomb et aux débuts du colonialisme, évoque les contradictions, les complexités et les multiples perspectives qui caractérisent les Caraïbes contemporaines et leur représentation dans l’art. Selon un témoignage cité par le conservateur et critique d’art Gerardo Mosquera, Christophe Colomb — qui espérait avoir trouvé les « Indes » — demanda aux Indiens autochtones de Cuba si cette terre était une île ou un continent. Les Indiens, pour qui la mer était un ensemble de couloirs et de passerelles menant à une myriade d’autres îles, répondirent que c’était une terre infinie dont personne n’avait vu la fin. La formule « île infinie » suggère la tension entre confinement et expansion, insularité et interconnections mondiales, qui définit aujourd’hui les Caraïbes et leurs liens géopolitiques avec le reste du monde — une tension qui est une force vivante dans leur culture et leur art. Les définitions eurocentriques des Caraïbes sont issues de l’héritage de l’esclavage et du colonialisme mais, dans le même temps, le mélange des cultures de l’ère postcoloniale, allié à la migration de la diaspora moderne à l’étranger, a donné naissance à une culture dynamique, souple, en constante mutation, qui génère de nouvelles perspectives.

L’exposition est organisée autour de quatre thèmes imbriqués, omniprésents dans les oeuvres, qui sont autant de points d’entrée pour saisir la complexité du travail des artistes : identité et politique ; histoire et mémoire ; mythes, religion et croyances ; et culture populaire. En abordant ces thèmes, les artistes soulèvent les questions de l’isolement, de l’émigration et du déplacement, et explorent les transformations sociopolitiques et culturelles récentes des Caraïbes. Ils remettent en question les stéréotypes qui circulent sur la région et offrent diverses interprétations d’une identité caribéenne constamment réimaginée.

Tumelo Mosaka

Conservateur adjoint, Expositions -

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art (Isla infinita: arte contemporáneo del Caribe)

Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art (Isla infinita: arte contemporáneo del Caribe) es una selección diversa y estimulante de los trabajos recientes de 45 artistas caribeños establecidos y prometedores en pintura, instalación, fotografía, grabado, dibujo, video y escultura. Algunos de los artistas participantes viven y trabajan en la región mientras otros se han establecido en el exterior, reflejando la diáspora caribeña moderna en centros metropolitanos de todo el mundo, inclusive Brooklyn, donde radica una de las comunidades caribeñas más numerosas de los Estados Unidos.

El título Infinite Island (Isla infinita), que alude a los viajes de Colón y los comienzos de la colonia, evoca las contradicciones, complejidades y perspectivas múltiples que caracterizan el Caribe contemporáneo y su proyección en el arte. De acuerdo con una versión que cita el curador y crítico de arte Gerardo Mosquera, Colón, esperando haber encontrado “las Indias”, les preguntó a los indígenas de Cuba si esa tierra era una isla o un continente. Los indios, que vislumbraban los mares abiertos como corredores y puentes a numerosas otras islas, replicaron que era una tierra infinita cuyo fin nadie había visto. La frase “isla infinita” sugiere la tensión entre contención y expansión, insularidad e interconexiones globales que continúa definiendo al Caribe y sus relaciones geopolíticas con el resto del mundo, una tensión que es fuerza viva en su cultura y su arte. Las definiciones eurocéntricas del Caribe forman parte del legado de esclavitud y colonialismo; al mismo tiempo, sin embargo, la mezcla post colonial de culturas junto con la diáspora moderna de emigración ha creado una cultura dinámica, flexible que se transforma constantemente y que genera nuevas perspectivas.

La exposición presenta cuatro temas que se superponen a lo largo del arte a la vista, como puertas de entrada a la complejidad de las obras: identidad y política; historia y memoria; mito, religión y creencia, y cultura popular. Comprometidos con estos temas, los artistas enfrentan cuestiones de aislamiento, migración y desplazamiento del Caribe y exploran cambios sociopolíticos y culturales recientes. Cuestionan los estereotipos actuales sobre la región y ofrecen una variedad de perspectivas sobre una identidad caribeña que se reinventa continuamente.

Tumelo Mosaka

Curador Asociado de Exposiciones -

Identidad e Política • Identity and Politics • Identité et Politique

La política de identidad tiene que ver con el poder y el control. ¿Quién habla por quién? ¿Qué define a la comunidad? Si bien los gobiernos pueden adoptar identidades nacionales que articulan un ideal oficial unificado tal como la noción de una cultura híbrida cohesiva y particular de la región, la realidad de la experiencia individual es mucho más compleja. La importancia de una identidad nacional en contraposición a una identidad regional, por ejemplo, puede variar de acuerdo con la ubicación geográfica o el origen étnico de la persona. Algunos de estos artistas presentan perspectivas minoritarias, incluso las de afrocubanos, miembros de una comunidad tradicional Maroon en Surinam e indocumentados que han migrado dentro de la región.

Para otros artistas, el tema de la identidad aflora como una estrategia para rechazar definiciones preestablecidas y asumir otra imagen de sí, fluida y variable. Los artistas pueden valerse de la ficción o la fragmentación para rehacer las narrativas históricas y las identidades sociales. Las obras en técnicas mixtas de Ewan Atkinson escenifican ambientes imaginarios que recalcan la inculcación de valores y moral relacionados con el régimen colonial en la sociedad caribeña. Las actuaciones e instalaciones de Jean-Ulrick Désert examinan cómo distintos signos como el color de la piel, la vestimenta y el lenguaje determinan la jerarquía social y se utilizan para categorizar al individuo en un contexto global. Christopher Cozier visualiza el Caribe como un producto de la colonia que ahora busca sus raíces modernas. Su obra, que utiliza el formato de diario personal en un cuaderno de artista, se basa en la dinámica histórica que conforma una nueva visión post colonial. Para otros, como Ebony Grace Patterson, el tema central es la diferencia entre los géneros. La obra de Patterson revisualiza la explotación y fetichización del cuerpo femenino negro como abstracción literal y conceptual. Para ella y para muchos otros artistas en esta exposición, la obra de arte es el ámbito que posibilita la transformación.

•

The politics of identity concern power and control. Who speaks for whom? What defines community? Who speaks for that community? While governments may embrace national identities that articulate a unified official ideal such as the notion of a new hybrid culture that is cohesive and unique to the region, the reality of individual experience is much more complex. The importance of national versus regional identity, for example, may shift according to one’s geographical location or ethnicity. Some of the artists here present minority perspectives, including those of Afro-Cubans, members of a traditional Maroon community in Suriname, and undocumented immigrants who have migrated within the region.

For other artists, the theme of identity surfaces as a strategy of rejecting prescribed definitions and reimagining the self as unfixed and mutable. Artists may use fiction or fragmentation to reshape historical narratives and social identities. Ewan Atkinson’s mixed-media works depict staged actions in imaginary environments that draw attention to the inculcation of values and morals associated with colonialism in Caribbean society. Jean-Ulrick Désert’s performances and installation works examine how various signifiers such as skin color, clothing, and language determine social hierarchy and are used to categorize individuals in a global context. Christopher Cozier envisions the Caribbean as a product of colonialism now in search of its modern roots. His work, using the personal-diary format of the artist notebook, is grounded in the historical dynamics that shape a new postcolonial vision. Others such as Ebony Grace Patterson focus on gender as the central issue. The exploitation and fetishization of the black female body is revisited in Patterson’s work as a literal and conceptual abstraction. For her, and many other artists in this exhibition, the work of art is a site where transformation is made possible.

•

La politique de l’identité est liée au pouvoir et au contrôle. Qui parle au nom de qui ? Qu’est-ce qui définit une communauté ? Qui défend les intérêts de cette communauté ? Si les gouvernements peuvent embrasser des identités nationales articulant un idéal officiel unifié, tel que la notion d’une nouvelle culture hybride cohérente et unique à la région, la réalité de l’expérience individuelle est bien plus complexe. L’importance accordée à l’identité nationale, par rapport à l’identité régionale, par exemple, peut varier selon le lieu géographique ou le groupe ethnique. Certains artistes présentent ici le point de vue de minorités, y compris celui d’Afro-Cubains membres d’une communauté traditionnelle de Marrons au Suriname, et de sans papiers qui ont émigré dans la région.

Pour d’autres artistes, le thème de l’identité devient une stratégie qui permet de rejeter les définitions établies et d’imaginer une nouvelle vision de soi, malléable et souple. Les artistes ont parfois recours à la fiction ou à la fragmentation pour refondre les récits historiques et les identités sociales. Les oeuvres en média mixte d’Ewan Atkinson décrivent des environnements imaginaires dans lesquels des actions mises en scène appellent l’attention sur l’inculcation de valeurs et d’une moralité associées au colonialisme dans la société caribéenne. Les performances et les installations de Jean-Ulrick Désert examinent la manière dont divers signifiants, comme la couleur de la peau, l’habillement et le langage, déterminent la hiérarchie sociale et servent à catégoriser les individus dans un contexte mondial. Christopher Cozier voit dans les Caraïbes un produit du colonialisme aujourd’hui en quête de ses racines modernes. Son travail, qui adopte le format du journal personnel d’un cahier d’artiste, se fonde sur la dynamique historique qui définit une nouvelle vision postcoloniale. D’autres artistes, comme Ebony Grace Patterson, placent la question de la spécificité des sexes au coeur de leur travail. L’exploitation et la fétichisation du corps féminin noir sont réexaminées par Patterson, en tant qu’abstraction littérale et conceptuelle. Pour elle, et pour beaucoup d’autres artistes dans cette exposition, l’oeuvre d’art est un site où la transformation devient possible.

-

Cultura Popular • Popular Culture • Culture Populaire

Aunque la cultura global de masas ha influido sobre el Caribe, la región también es productora y exportadora clave de cultura popular a todo el mundo. De hecho, el proceso continuo de intercambio y reinterpretación dentro de la región y su diáspora le da un dinamismo particular a la cultura popular del Caribe.

La música popular es un vehículo importante de interacción, apropiación y autodefinición cultural en el Caribe. En toda la historia de la región, la reinterpretación de influencias externas por músicos del Caribe ha dado lugar a formas musicales innovadoras como el calipso y el “reggae”. El calipso, que se originó en Trinidad y Tobago, tiene una larga relación con el carnaval, donde ha servido de amplio lente por el que se examinan, valiéndose de la parodia y la exageración, los males de la sociedad. El “reggae”, género musical que nació en Jamaica y que popularizó Bob Marley, trata de concientizar la injusticia social a nivel político. Aunque estos formatos musicales se asocian con la identidad nacional, ambos critican mayormente el statu quo. A su vez, nuevas formas culturales también han apropiado, subvertido y transformado estos géneros musicales. El “reggae”, por ejemplo, dio lugar a géneros populistas como el “dancehall” y el regatón. Estos nuevos géneros atraen a públicos más jóvenes y más rebeldes, mientras que su letra de consumismo y sexualidad cruda y estentórea contradicen con frecuencia las nociones de independencia nacional y liberación que se asociaron inicialmente con el “reggae”.

Los ritmos musicales y estilos de baile caribeños inspiraron a varios artistas de esta exposición. Storm Saulter, por ejemplo, documenta y manipula metraje de fiestas de “dancehall” para destacar cómo el exhibicionismo y la ostentación sexualizada de estos eventos sirven para diversos modos de darse a conocer y conocerse a sí mismo, mientras que Melvin Moti explora cómo la música es un indicador de la historia a través de su representación de Miss Daisy, reina de antaño del “ska”. Dub Ramp (Brinco Dub) de Satch Hoyt comenta sobre la intersección de música “dub” de Jamaica, género que mezcla elementos de grabaciones existentes, y la apropiación por los antillanos del cricket, un deporte colonial.

•

Although the Caribbean has been influenced by global mass culture, the region is also a key producer and exporter of popular culture to the world. In fact, it is the continual process of exchange and reinterpretation within the region and its diaspora that gives particular dynamism to Caribbean popular culture.

Popular music is a key vehicle of cultural interaction, appropriation, and self-definition in the Caribbean. Throughout the history of the region,the reinterpretation of external influences by Caribbean musicians has given rise to innovative musical forms such as calypso and reggae. Calypso, originating in Trinidad and Tobago, has a long association with the carnival, where it has served as a wide lens through which social ills are examined by means of parody and exaggeration. Reggae, the musical form born in Jamaica and made popular by Bob Marley, attempts to raise political consciousness of social injustice. Both musical forms, though associated with national identity, have been largely critical of the status quo. These musical genres have also been appropriated in turn, subverted and transformed into new cultural forms. Reggae, for example, gave rise to populist genres such as dancehall and reggaeton. These new forms appeal to younger, more rebellious audiences, while their raw, loud lyrics of consumerism and sexuality are often antithetical to the ideas of nationhood and liberation initially associated with reggae.

Caribbean musical rhythms and dance styles serve as inspiration for several artists in the exhibition. Storm Saulter, for example, documents and manipulates footage of dancehall parties in order to highlight the way in which the exhibitionism and sexualized display that occur at these events are opportunities for various enactments and definitions of self, while Melvin Moti explores how music is a marker of history through his portrayal of Miss Daisy, old-time queen of ska. Satch Hoyt’s Dub Ramp comments on the intersection of Jamaican dub music, a genre that remixes elements from existing recordings, and the West Indian appropriation of the colonial sport of cricket.

•

Bien que les Caraïbes aient subi l’influence de la culture de masse mondiale, la région est aussi une source importante de culture populaire qui s’exporte dans le monde entier. En fait, c’est le processus continu d’échange et de réinterprétation au sein de la région et de sa diaspora qui donne un dynamisme particulier à la culture populaire caribéenne.

Dans les Caraïbes, la musique populaire est un véhicule essentiel d’interaction culturelle, d’appropriation et d’autodéfinition. Pendant toute l’histoire de la région, la réinterprétation d’influences venues de l’étranger par les musiciens caribéens a donné naissance à des formes d’expression musicale innovantes, telles que le calypso et le reggae. Le calypso, originaire de Trinité-et-Tobago, est depuis longtemps associé au carnaval, où il a servi de miroir révélateur des maux de la société à l’aide de la parodie et de l’exagération. Le reggae, forme d’expression musicale née en Jamaïque et rendue populaire par Bob Marley, tente de faire naître une conscience politique face à l’injustice sociale. Ces deux formes d’expression musicale, bien qu’associées à une identité nationale, ont souvent critiqué le statut quo. À leur tour, ces genres musicaux ont aussi été appropriés, subvertis et transformés en de nouvelles formes d’expression culturelle. C’est du reggae, par exemple, que découlent des genres populistes comme le dancehall et le reggaeton. Ces nouvelles formes séduisent un public plus jeune, plus rebelle, alors que le consumérisme et la sexualité qu’expriment leurs paroles crues et violentes sont souvent l’antithèse des concepts de nation et de libération initialement associés au reggae.

Les rythmes musicaux et les danses des Caraïbes ont inspiré plusieurs artistes figurant dans l’exposition. Storm Saulter, par exemple, documente et manipule des images tournées dans des soirées de dancehall pour montrer comment l’exhibitionnisme et la sexualité affichée qui caractérisent ces manifestations sont autant d’opportunités de se mettre en scène et de se définir. Melvin Moti, de son côté, explore la façon dont la musique marque les étapes de l’histoire à travers son portrait de Miss Daisy, ancienne reine de ska. Dub Ramp (Rampe Dub) de Satch Hoyt est un commentaire sur le croisement du dub jamaïcain, un genre qui remixe des éléments d’enregistrements existants, et l’appropriation du criquet, le sport des colons, par les Antillais.

-

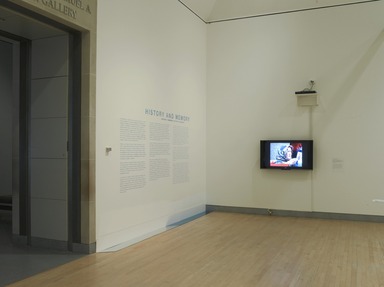

Historia y Memoria • History and Memory • Histoire et Mémoire

Históricamente, el Caribe ha sido un crisol de migraciones y cambios sin fin de residencia. Aun antes de la llegada de los europeos, los indígenas se mudaban de isla en isla de acuerdo con sus necesidades y deseos. Con la llegada y el establecimiento de los europeos, el sistema de plantaciones y la colonia dieron lugar al exterminio de poblaciones indígenas, masacradas por los colonizadores o muertas por hambrunas o enfermedades traídas del extranjero. La mano de obra que los colonos europeos importaron para las plantaciones fue el africano esclavizado y, más tarde, el trabajador indígena ligado por contrato. Hoy, los descendientes de estos trabajadores y colonos moldean y definen una cultura caribeña híbrida.

Debido a esta historia, el teórico Stuart Hall describió el Caribe como “un lugar donde todos vienen de otro lugar”. Recientemente las presiones económicas, los disturbios políticos y otros factores dieron lugar a una migración en gran escala de la región a centros metropolitanos de todo el mundo que redefinió la diáspora caribeña. Este fenómeno ha añadido mayor complejidad a la mezcla de culturas que afecta la identidad caribeña, manteniéndola en flujo constante, incorporando el pasado y el presente.

Muchos artistas de la exposición exploran el impacto y legado de la colonia que siguen definiendo las relaciones sociales de la región y de su diáspora. Se compara a menudo el arrebato del poder y la explotación de poblaciones locales por parte de la industria extranjera y del turismo con la experiencia histórica de esclavización de los antepasados africanos.

Los artistas Terry Boddie y Charles Campbell, por ejemplo, usan imágenes icónicas del cargamento humano esclavo como un recordatorio de la horrible y traumática experiencia de la Travesía del Atlántico, el viaje que transportó a los africanos a través del océano hasta las plantaciones del Caribe y de las Américas. Hew Locke apela a un enfoque distinto al explorar el legado de la colonia por medio de símbolos del poder continuativo de la monarquía británica en el Caribe y África.

•

Historically, the Caribbean has been a crucible of unending migration and relocation. Even before the arrival of Europeans, the indigenous Indians moved between the islands according to their needs and desires. With the arrival and settlement of Europeans, the plantation system and colonialism led to the extermination of indigenous populations, who were massacred by the colonizers or died of famine or foreign disease. The European settlers imported a workforce of enslaved African people and, later, indentured Indian laborers for the plantations. Today, the descendants of these workers and colonizers shape and define a hybrid Caribbean culture.

Because of this history, the cultural theorist Stuart Hall has described the Caribbean as “a place where everybody comes from somewhere else.” Recently, economic pressures, political turmoil, and other factors have caused migration in large numbers from the region to metropolitan centers around the world, redefining the Caribbean diaspora. This phenomenon has added further complexity to the mix of cultures affecting Caribbean identity, keeping it constantly in flux, incorporating past and present.

Many artists in the exhibition explore the impact and legacy of colonialism, which has continued to define social relations in the region and its diaspora. The disempowerment and exploitation of local populations by foreign industry and tourism are often likened to the historical experience of enslaved African ancestors. The artists Terry Boddie and Charles Campbell, for example, use iconic images of human slave cargo as a reminder of the horrific and traumatic experience of the Middle Passage, the voyage that transported Africans across the Atlantic to the plantations of the Caribbean and the Americas. Hew Locke takes a different approach, exploring the legacy of colonialism through symbols of the continuing power of the British monarchy within the Caribbean and Africa.

•

De tout temps, les Caraïbes ont été un creuset de migrations et de déplacements incessants. Avant même l’arrivée des Européens, les Indiens autochtones voyageaient d’une île à l’autre au gré de leurs besoins et de leurs désirs. Après que les Européens s’y soient installés, le système des plantations et le colonialisme conduirent à l’extermination des populations autochtones, qui furent massacrées par les colonisateurs ou succombèrent à la famine ou à des maladies venues de l’étranger. Les colons européens importèrent une main-d’oeuvre composée d’Africains réduits en esclavage et, plus tard, d’Indiens asservis pour cultiver les plantations. Aujourd’hui, les descendants de ces travailleurs et des colonisateurs forment et définissent une culture caribéenne hybride.

En se fondant sur cette histoire, le théoricien culturel Stuart Hall a décrit les Caraïbes comme « un endroit où tout le monde vient d’ailleurs ». Récemment, les pressions économiques et les bouleversements politiques, entre autres facteurs, ont poussé un grand nombre d’habitants de la région à émigrer dans les métropoles du monde entier et à redéfinir la diaspora caribéenne. Ce phénomène a ajouté un degré supplémentaire de complexité au mélange culturel dont découle l’identité caribéenne, assurant sa mutation continue et intégrant passé et présent.

Beaucoup d’artistes participant à l’exposition explorent l’impact et l’héritage du colonialisme, qui définit toujours les relations sociales dans la région comme au sein de la diaspora. La perte d’autonomie et l’exploitation des populations locales par l’industrie et le tourisme étrangers sont souvent comparées à l’expérience de leurs ancêtres africains réduits en esclavage dans le passé. Terry Boddie et Charles Campbell, par exemple, utilisent dans leurs oeuvres les images iconiques d’un chargement d’esclaves humains pour rappeler l’expérience horrifiante et traumatisante du Passage du Milieu, la traversée de l’Atlantique par des Africains transportés dans les plantations des Caraïbes et des Amériques. Hew Locke adopte une approche différente et explore l’héritage du colonialisme à travers les symboles du pouvoir ininterrompu de la monarchie britannique dans les Caraïbes et en Afrique. -

Mito, Religión y Creencia • Myth, Religion, and Belief • Mythes, Religion et Croyances

Aunque las religiones principales de las islas del Caribe son variantes del cristianismo, varias de ellas son el producto directo de influencias africanas. La confluencia de antiguas prácticas culturales africanas con el cristianismo europeo impuesto a la fuerza a los esclavos dio lugar a nuevas religiones sincréticas (las que combinaban las tradiciones y creencias africanas y europeas) como vudú, santería, candomblé, ifa, palo monte y otras. Los creyentes de muchas de estas religiones rinden culto a los orishas (dioses de la cultura Yoruba del África occidental) que poseen poderes divinos y son mediadores entre el reino humano y el espiritual. Dichas tradiciones sobrevivieron porque los primeros esclavos que practicaban estas religiones ocultaron las raíces africanas de los orishas apropiándose de la iconografía cristiana. En la santería cubana, por ejemplo, San Antonio el custodio se convirtió en Elegbá, guardián de las encrucijadas.

El aspecto político de la religión caribeña se manifiesta en las apropiaciones de las religiones sincréticas que permitían al esclavizado y a sus descendientes transmitir sus tradiciones de generación en generación a modo de resistencia y preservación cultural. En Haití, el vudú se convirtió en un vehículo de movilización política que fue proscrito primero por la colonia y después por la clase gobernante hasta 1946. El rastafarianismo jamaiquino, un movimiento político y religioso, considera que las naciones independientes de África, especialmente Etiopía, son símbolos de liberación y libertad.

La práctica y política de la religión caribeña han sido terreno fértil para los artistas contemporáneos. Marta María Pérez Bravo, por ejemplo, documenta su propia representación de rituales que encarnan misterios sagrados relacionados con las religiones afrocubanas de santería y palo monte. Luego manipula estas fotografías en el cuarto oscuro para sugerir la transformación de sí misma dentro del ritual religioso. La obra de Santiago Rodríguez Olazábal se relaciona íntimamente con su experiencia como sacerdote del culto ifa de los orishas. Otros, como Alex Burke, se muestran más ambiguos hacia la historia y la religión. Las esculturas de tela de Burke, confeccionadas con fragmentos de trapos recirculados, aluden a los misterios del vudú y las mitologías de las “muñecas del vudú” pero también sugieren la supervivencia y continuación de la cultura en el Caribe.

•

While the dominant religions of the Caribbean islands are variants of Christianity, several of them are the direct product of African influences. The confluence of ancient African cultural practices and the European Christianity that was forced on slaves gave rise to new syncretic religions (those combining African and European traditions and beliefs) such as Vodun, Santeria, Candomble, Ifa, Palo Monte, and others. Believers in many of these religions worship orishas (gods of West African Yoruba culture) that possess divine powers and mediate between human and spiritual realms. Such traditions survived because early slave practitioners of these religions disguised the African roots of the orishas by appropriating Christian iconography. In Cuban Santeria, for example, Saint Anthony the gatekeeper became Elegba, guardian of the crossroads.

The political aspect of Caribbean religion is manifest in the appropriations of syncretic religions that allowed the enslaved and their descendants to pass their traditions down through generations as a form of resistance and cultural preservation. In Haiti, Vodun became a vehicle of political mobilization that was outlawed under colonialism and later by the ruling class until 1946. Jamaican Rastafarianism, a political and religious movement, looks to independent nation states of Africa, specifically Ethiopia, as symbols of liberation and freedom.

The practice and politics of Caribbean religion have provided fertile ground for contemporary artists. Marta Maria Pérez Bravo, for example, documents her own performance of rituals that embody sacred mysteries linked to the Afro-Cuban religions of Santeria and Palo Monte. She then manipulates these photographs in the darkroom to suggest the transformation of the self within religious ritual. The work of Santiago Rodríguez Olazábal is closely related to his experience as a priest of the cult of the orisha Ifa. Others such as Alex Burke approach history and religion in a more ambiguous way. Burke’s fabric sculptures made of fragments of recycled rags refer to the mysteries of Vodun and the mythologies of “voodoo dolls” but also suggest the survival and continuation of culture in the Caribbean.

•

Si les principales religions des Îles Caraïbes sont des variantes du christianisme, plusieurs d’entre elles sont directement issues d’influences africaines. La convergence d’anciennes pratiques culturelles africaines et du christianisme européen imposé aux esclaves a donné naissance à de nouvelles religions syncrétiques (qui combinent les traditions et les croyances africaines et européennes) telles que le vodou, la santéria, le candomblé, l’ifa et le palo monte, entre autres. Dans un grand nombre de ces religions, les croyants vénèrent des orishas (divinités dans la culture yoruba d’Afrique de l’Ouest) qui possèdent des pouvoirs divins et servent de médiateurs entre le royaume des hommes et celui des esprits. Ces traditions ont survécu parce que les esclaves qui les pratiquaient à l’origine ont dissimulé les racines africaines des orishas en plaquant sur elles une iconographie chrétienne. Dans la santéria cubaine, par exemple, Saint Antoine, gardien des portes du paradis, a été assimilé à Elegba, gardien des carrefours.

L’élément politique de la religion caribéenne est évident dans les appropriations effectuées par les religions syncrétiques, qui ont permis aux esclaves et à leurs descendants de transmettre leurs traditions de génération en génération, constituant une forme de résistance et de préservation culturelle. En Haïti, le vodou est devenu un instrument de mobilisation politique qui fut déclaré hors la loi à l’époque coloniale et, plus tard, par la classe dirigeante jusqu’en 1946. Le rastafarianisme jamaïcain, un mouvement politique et religieux, voit dans les Étatsnations indépendants d’Afrique, notamment l’Éthiopie, des symboles de libération et de liberté.

Qu’il s’agisse de pratique ou de politique, la religion caribéenne offre un terrain fertile aux artistes contemporains. Marta Maria Pérez Bravo, par exemple, se photographie en train d’accomplir des rituels qui incarnent les mystères sacrés de la santéria et du palo monte afrocubains. Elle manipule ensuite ces images en laboratoire pour suggérer la transformation de soi qui s’opère pendant ce rituel religieux. Le travail de Santiago Rodríguez Olazábal est étroitement lié à son expérience de prêtre du culte de l’orisha ifa. D’autres, comme Alex Burke, portent un regard plus ambigu sur l’histoire et la religion. Les sculptures en tissu de Burke composées de fragments de chiffons recyclés font référence aux mystères du vodou et à la mythologie des « poupées vodous », mais suggèrent aussi la survie et la continuation de la culture des Caraïbes.

-

July 7, 2007

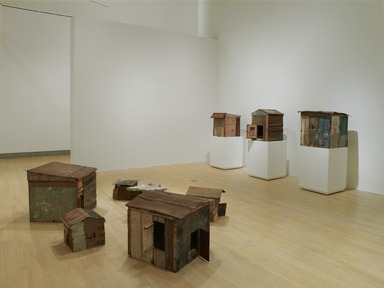

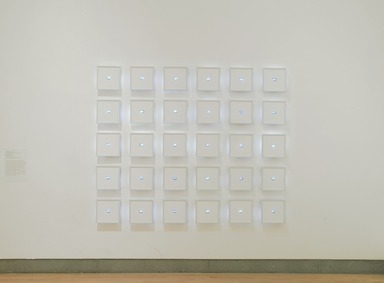

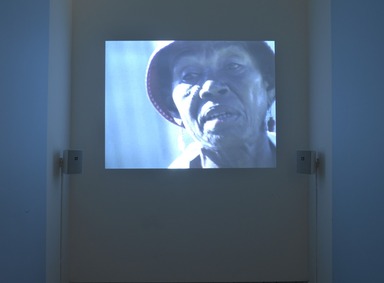

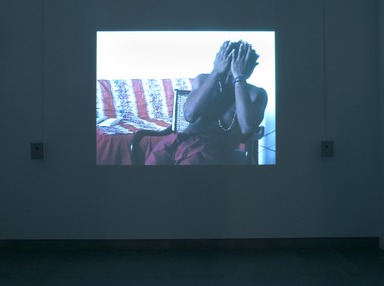

The exhibition Infinite Island: Contemporary Caribbean Art examines how the Caribbean is defined, as both a real and an imaginary location. Including nearly 80 works in a wide range of media, created within the past six years by 45 emerging and established artists, it will be presented at the Brooklyn Museum from August 31, 2007 through January 27, 2008.

The exhibition approaches the Caribbean as a uniquely flexible space, where culture and history offer multiple possibilities of interpreting contemporary Caribbean experience. The mix of cultures created by slavery and colonialism, along with the modern Diaspora of Caribbean people migrating to metropolitan centers around the world, has shaped a dynamic culture incorporating distinct histories and artistic traditions. Despite their idyllic beauty Caribbean nations struggle with legacies of Colonialism and nationalism, as they search for new identities. These issues, along with the multiplicity of religious beliefs and contemporary popular culture have generated new perspectives on Caribbean identity and experience.

The artists represented have ties to 14 Caribbean nations: Barbados, Cuba, Curaçao, the Dominican Republic, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, Martinique, Monserrat, Nevis, Puerto Rico, St. Martin, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. The exhibition will be organized around the themes of History and Memory, Politics and Identity, Myth, Ritual and Belief, and Popular Culture. These themes provide entry points into the complexity of artworks. The artists employ a range of materials that include traditional materials and industrial objects such as discarded automobile tires and plastic plates. These works include paintings, photography, prints and other works on paper, video, installation works, and sculpture.

Among the works included is El Dorado, a mixed-media piece by Hew Locke, who was raised in Guyana and now lives and works in London. The large-scale work is a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II, adorned with low-culture objects to subvert the power usually associated with the monarchy. Nicole Awai, a Trinidadian now living in Brooklyn, has created a complex image with graphite, paint, nail polish and glitter on paper titled Specimen from L. E. (Local Ephemera): Resistance with Black Ooze. Jean-Ulrick Désert, a Haitian artist who now divides his time between New York City and Berlin, has created an installation of four mannequins clad in the flags of the former colonial powers that dominated the Caribbean titled Burqa Project: On the Border of My Dreams I Encountered My Double’s Ghost. A diptych series by Quisqueya Henríquez, from Cuba and now living in the Dominican Republic, explores the contrast between the ideal as might be seen by a tourist alongside the reality of the poverty in which some Caribbeans exist, as reflected in a pair of sunglasses.

Organized by the Brooklyn Museum, the exhibition has been curated by Tumelo Mosaka, Assistant Curator, Contemporary Art and Exhibitions. A catalogue published by the Brooklyn Museum in association with Philip Wilson Publishers will accompany the exhibition.

The Brooklyn Museum Web site will feature a page with information about the newly commissioned and site-specific works presented in Infinite Island. Web visitors will be able to view images, submit questions to participating artists, and leave comments at www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/infinite_island/.

A wide range of public programs will be presented in conjunction with the exhibition, among them a film series, lectures, artists’ talks, and Infinite Island will be the theme of the October Target First Saturday.

Infinite Island is sponsored by Forest City Ratner Companies.

The exhibition is made possible by the Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Exhibition Fund and the Barbara and Richard Debs Exhibition Fund. Generous support is contributed by the Peter Norton Family Foundation, the American Center Foundation, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional funding is contributed by the Friends of Brooklyn Museum, the Mondriaan Foundation, Amsterdam, and the Consulate General of the Netherlands. AM NewYork is media sponsor. The accompanying catalogue is supported by a Brooklyn Museum publications endowment established by the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

View Original