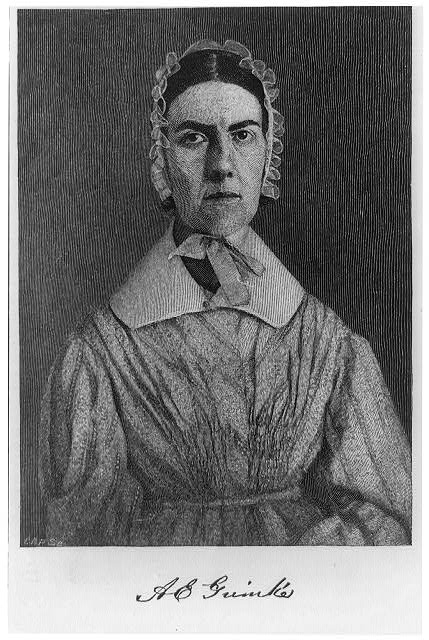

Angelina Grimké

b. 1805, Charleston, South Carolina; d. 1879, Boston

Born into a slaveholding family in Charleston, the Grimké sisters, Sarah and Angelina, repudiated their southern values and moved to Philadelphia, where they joined the antislavery crusade. They entered the fray in 1836 with two pamphlets: Angelina’s An Appeal to the Christian Women of the South and Sarah’s Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern States. Angelina’s tract argued that southern women were morally obligated to eradicate slavery. Sarah’s Epistle debunked the biblical justification for slavery. Both were burned in the South and the Grimkés were threatened with imprisonment should they return to Charleston. Self-educated women who had witnessed the evils of the “peculiar institution” firsthand, the Grimké sisters became the first female agents of the American Anti-Slavery Society, lecturing to large crowds of men and women. Angelina—dubbed “Devilina” by opponents—was an especially powerful orator. Their popularity prompted the General Association of Congregational Ministers of Massachusetts to issue a statement in 1837 condemning the sisters’ violation of gender norms by speaking to mixed audiences. The ministers’ position received widespread support, including from Catharine Beecher, who rebuked Angelina for stepping outside a woman’s proper domain. The Grimkés now took on another battle: women’s rights. Angelina penned the Appeal to the Women of the Nominally Free States (1837), arguing that women shared with men equal responsibility for slavery, and therefore equal responsibility for destroying it. Sarah authored the first women’s rights tract in the U.S., Letters on the Equality of the Sexes and the Condition of Women (1838), which profoundly influenced first-wave feminists, including Mott, Stanton, and Stone. The Grimké sisters paid a heavy price for their uncompromising activism. Their abolitionist and feminist positions constituted the radical end of the ideological spectrum and alienated not only the usual suspects but many inside the movements. In 1838, Angelina married fellow abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld. After collaborating on American Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (1839), they moved with Sarah to Belleville, New Jersey, and opened a school.

Unknown artist. Angelina Emily Grimké 1805–18805–1879), n.d. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

Related Place Setting

Related Heritage Floor Entries

- Marian Anderson

- Josephine Baker

- Mary McLeod Bethune

- Anne Ella Carroll

- Mary Ann Shad Cary

- Prudence Crandall

- Milla Granson

- Sarah Grimke

- Frances Harper

- Zora Neale Hurston

- Edmonia Lewis

- Mary Livermore

- Bessie Smith

- Maria Stewart

- Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Harriet Tubman

- Margaret Murray Washington

- Ida B. Wells