Trotula

(b. unknown; d. 1097, Salerno, Italy)

Trotula of Salerno (also known as Trotula of Ruggerio) was an eleventh-century Italian doctor, who is frequently regarded as the world’s first gynecologist. Her many achievements in the male-dominated specialty of gynecology both educated her contemporaries and advanced progressive ideas about women’s health care.

Trotula served as a physician and professor at the Medical School in Salerno, Italy, the first medical school in the world. Her husband and sons were also doctors at the school, which was one of the only schools in Europe to instruct and employ both men and women. Trotula distinguished her work with a specific focus on the medical needs of women. Attentive to women’s diseases and overall health, she became highly skilled at diagnosing uniquely female medical issues ranging from pregnancy-related complications to those related to female hygiene. She advocated for the use of opiates during labor, opposing the Christian belief of the time that women should experience a maximum of suffering during childbirth as punishment for Eve‘s sin. She also revolutionized the medical field by suggesting that men could also be infertile.

Trotula’s work was so influential that it set the course for the practice of women’s medicine for centuries. Long after her death, doctors throughout the medieval world relied on her medical reference work to treat female patients. Trotula Major on Gynecology, also known as Passionibus Mulierum Curandorum (The Diseases of Women), was a sixty-three chapter book first published in Latin in the 12th century; it is still regarded as the definitive sourcebook for pre-modern medical practices. The only book written to educate male doctors about the female body, it included information about menstruation and childbirth in addition to general medical advice. This text had a great impact on the practice of medicine during the pre-modern period.

During the Renaissance, some scholars began to express doubt that Trotula was a woman, and others believed she was an entirely fictional character. It was supposed that a male physician Trottus had written the complex material in Trotula Major, and that Trotula was a midwife. Though scholars today believe she did, in fact, exist, there is continued research into whether Trotula’s writings are solely hers or compiled from many authors.

Trotula at The Dinner Party

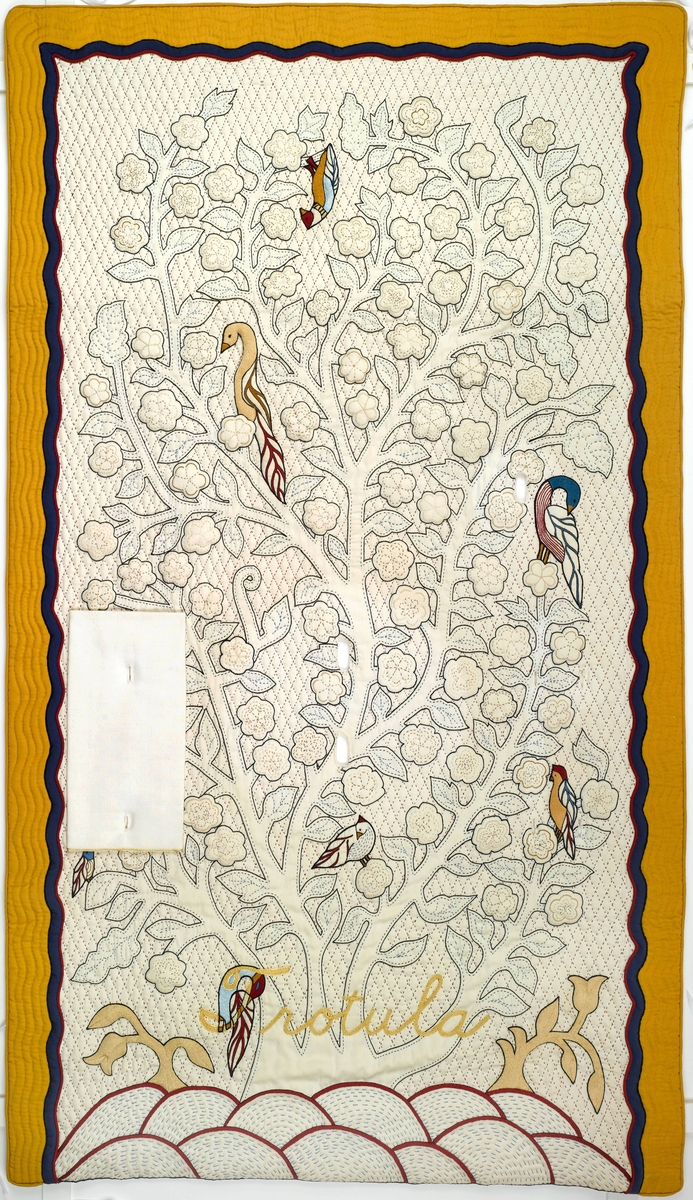

Trotula’s place setting combines references to her role as a doctor with childbirth and caretaking. The Tree of Life image in the runner highlights Trotula’s profession as a gynecologist. Tree of Life imagery has a strong and evolving heritage, beginning in ancient times and continuing into Christianity, as a symbol of life and regeneration.

In creating the runner, Chicago chose to use the trapunto technique with a quilt that can be dated back to 11th century Sicily. The white fabric of the runner is reminiscent of swaddling cloth, and the piece itself is a quilt, creating a visual link to the familiar baby blanket.

Trotula’s plate features a birthing image, as well as serpentine imagery that resembles the caduceus, a symbol for medicine and doctors that is now used as the symbol for the American Medical Association. These serpentine forms also reference the Aztec fertility goddess who served as the patron of midwives. Chicago chose the snake motif “because of its historical association with feminine wisdom and powers of healing” (Chicago, A Symbol of Our Heritage, 74).

Primary Sources

Trotula di Ruggiero. De passionibus mulierum, or De aegritudinibus mulierum, or The Trotula Major, or Trotula. MS Bibliotheque Nationale, Lat. 7856.

Translations, Editions, and Secondary Sources

Barratt, Alexandra, ed. The Knowing of Woman’s Kind in Childing: A Middle English Version of Material Derived from the Trotula and Other Sources. Turnhout: Brepols, 2001.

Brown, Judith, and Robert Davis, eds. Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy. London and New York: Longman, 1998.

Cadden, Joan. The Meanings of Sex Difference in the Middle Ages: Medicine, Science, and Culture. Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Green, Monica H., ed. The Trotula: A Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

Maclean, Ian. The Renaissance Notion of Woman: A Study in the Fortunes of Scholasticism and Medical Science in European Intellectual Life. Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Mason-Hohl, Elizabeth. The Diseases of Women by Trotula of Salerno: A Translation of Passionibus Mulierum Curandorum. Los Angeles: Ward Ritchie, 1940.

Musacchio, Jacqueline M. The Art and Ritual of Childbirth in Renaissance Italy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

O’Dowd, Michael J. The History of Medications for Women: Materia Medica Woman. New York: Parthenon, 2001.

Rowland, Beryl, ed. Medieval Woman’s Guide to Health: The First English Gynecological Handbook. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1981.

Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Trotula place setting), 1974–79. Mixed media: ceramic, porcelain, textile. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. Photograph by Jook Leung Photography

Place Setting Images

Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Trotula plate), 1974–79. Porcelain with overglaze enamel (China paint), rainbow luster overglaze, and possibly paint, 14 × 14 × 1 3/16 in. (35.6 × 35.6 × 3 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago. (Photo: © Donald Woodman)

Judy Chicago (American, b. 1939). The Dinner Party (Trotula runner), 1974–79. Off-white cotton in satin weave, muslin, woven interface support material (horsehair, wool, and linen), cotton twill tape, silk, synthetic gold cord, colored cotton floss, quilted and appliquéd fabrics, cotton thread, 51 3/8 × 29 3/8 in. (130.5 × 74.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation, 2002.10. © Judy Chicago

Biographical Images

Related Heritage Floor Entries

Web Resources

Women and Medicine in the Middle Ages, by Jennifer A. Heise

Medieval Manuscripts in the National Library of Medicine

The Chaucer Name Dictionary—Trotula di Ruggiero