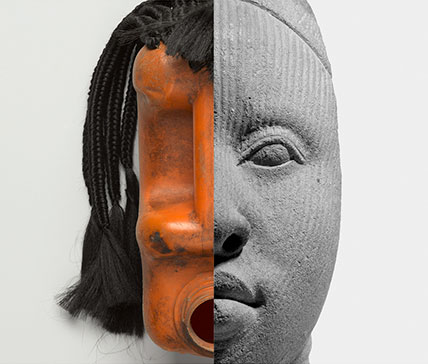

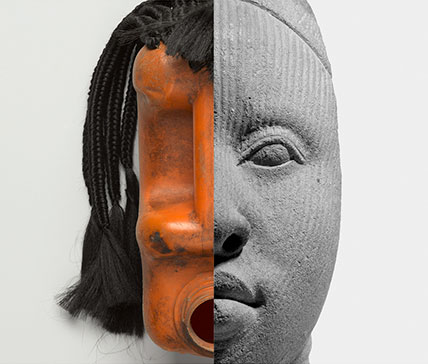

Romuald Hazoumé (Beninois, born 1962). Fiegnon (detail), 2011. Porto-Novo, Ouémé Department, Benin. Plastic jerry can, synthetic hair, copper wire, 11 × 8 × 81⁄2 in. (27.9 × 20.3 × 21.6 cm). Caroline A. L. Pratt Fund, 2014.32.2. © Romuald Hazoumé; Unidentified Yoruba artist. Fragment of a Head (detail), 1100–1500 C.E. Ife, Osun State, Nigeria. Terracotta, 6 × 31⁄4 x 33⁄4 in. (15.2 × 8.3 × 9.5 cm). Private collection, L54.5 (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

Romuald Hazoumé (Beninois, born 1962). Fiegnon (detail), 2011. Porto-Novo, Ouémé Department, Benin. Plastic jerry can, synthetic hair, copper wire, 11 × 8 × 81⁄2 in. (27.9 × 20.3 × 21.6 cm). Caroline A. L. Pratt Fund, 2014.32.2. © Romuald Hazoumé; Unidentified Yoruba artist. Fragment of a Head (detail), 1100–1500 C.E. Ife, Osun State, Nigeria. Terracotta, 6 × 31⁄4 x 33⁄4 in. (15.2 × 8.3 × 9.5 cm). Private collection, L54.5 (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

Left: Unidentified Chokwe artist. Chief’s Chair, 19th century, Angola. Copper alloy, animal hide, wood, 263⁄4 x 12 × 151⁄3 in. (67.9 × 30.5 × 39.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Museum Expedition 1922, Robert B. Woodward Memorial Fund, 22.187; Center: Gonçalo Mabunda (Mozambican, b. 1975). Harmony Chair, 2009, Maputo, Mozambique. Welded weapons (handguns, rifles, land mines, bullets, machine gun belts, rocket-propelled grenades), iron alloy, 481⁄16 x 383⁄16 x 2915⁄16 in. (122 × 97 × 76 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Samuel E. Haslett, by exchange; gift of Mrs. Morris Friedsam, Georgine Iselin, and Mrs. Joseph M. Schulte, by exchange; Designated Purchase Fund 2013.26.2. © Gonçalo Mabunda; Right: Cheick Diallo (Malian, born 1960). Sansa Chair, 2012, Bamako, Mali. Steel, nylon, 311⁄2 x 311⁄2 x 357⁄16 in. (80 × 80 × 90 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Mrs. Carl L. Selden, by exchange; gift of Mary Babbott Ladd and Frank L. Babbott, Jr. in memory of their father, Frank L. Babbott; gift of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and Mrs. H. A. Metzger, by exchange; Ella C. Woodward Memorial Fund, John B. Woodward Memorial Fund, and Designated Purchase Fund, 2013.26.1. © Cheick Diallo. (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

African artists have a long history of responding to fresh design concepts, while always revising them to ends both practical and novel. Together, these three works trace the evolution of a single form: first, as an imported idea became African, and then as contemporary artists adapted this African form for a global market.

Most seats in sub-Saharan Africa are low stools, carved from a single block of wood. Yet, as early as the sixteenth century, Portuguese traders and explorers introduced chairs with backs to southern and eastern Africa. Chokwe artists soon began to produce similar chairs, adding sculptural scenes and Chokwe motifs. This wood chair was carved as an object of status for a chief. In fact, none of these three chairs were meant for sitting. Gonçalo Mabunda’s Harmony chair uses decommissioned handguns, bullet belts, and other munitions collected from the estimated 7 million weapons left in Mozambique following the end of its civil war in 1992. Its design references a coastal East African tradition of high-backed chairs that were symbols of power and prestige, discussion and debate. The Sansa chair, an inventive deconstruction of the chair form, is among the original creations that have established Cheick Diallo as one of Africa’s leading contemporary designers. Built at Diallo’s direction by artisans from Bamako, the half-reclining Sansa chair seems to sit midway between a European notion of the chair as a leisure object and a West African idea of the chair as a support for displaying a person of status.

Left: Unidentified Chokwe artist. Chief’s Chair, 19th century, Angola. Copper alloy, animal hide, wood, 263⁄4 x 12 × 151⁄3 in. (67.9 × 30.5 × 39.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Museum Expedition 1922, Robert B. Woodward Memorial Fund, 22.187; Center: Gonçalo Mabunda (Mozambican, b. 1975). Harmony Chair, 2009, Maputo, Mozambique. Welded weapons (handguns, rifles, land mines, bullets, machine gun belts, rocket-propelled grenades), iron alloy, 481⁄16 x 383⁄16 x 2915⁄16 in. (122 × 97 × 76 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Samuel E. Haslett, by exchange; gift of Mrs. Morris Friedsam, Georgine Iselin, and Mrs. Joseph M. Schulte, by exchange; Designated Purchase Fund 2013.26.2. © Gonçalo Mabunda; Right: Cheick Diallo (Malian, born 1960). Sansa Chair, 2012, Bamako, Mali. Steel, nylon, 311⁄2 x 311⁄2 x 357⁄16 in. (80 × 80 × 90 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Mrs. Carl L. Selden, by exchange; gift of Mary Babbott Ladd and Frank L. Babbott, Jr. in memory of their father, Frank L. Babbott; gift of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and Mrs. H. A. Metzger, by exchange; Ella C. Woodward Memorial Fund, John B. Woodward Memorial Fund, and Designated Purchase Fund, 2013.26.1. © Cheick Diallo. (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

African artists have a long history of responding to fresh design concepts, while always revising them to ends both practical and novel. Together, these three works trace the evolution of a single form: first, as an imported idea became African, and then as contemporary artists adapted this African form for a global market.

Most seats in sub-Saharan Africa are low stools, carved from a single block of wood. Yet, as early as the sixteenth century, Portuguese traders and explorers introduced chairs with backs to southern and eastern Africa. Chokwe artists soon began to produce similar chairs, adding sculptural scenes and Chokwe motifs. This wood chair was carved as an object of status for a chief. In fact, none of these three chairs were meant for sitting. Gonçalo Mabunda’s Harmony chair uses decommissioned handguns, bullet belts, and other munitions collected from the estimated 7 million weapons left in Mozambique following the end of its civil war in 1992. Its design references a coastal East African tradition of high-backed chairs that were symbols of power and prestige, discussion and debate. The Sansa chair, an inventive deconstruction of the chair form, is among the original creations that have established Cheick Diallo as one of Africa’s leading contemporary designers. Built at Diallo’s direction by artisans from Bamako, the half-reclining Sansa chair seems to sit midway between a European notion of the chair as a leisure object and a West African idea of the chair as a support for displaying a person of status.

Left: Unidentified Chokwe artist. Chief’s Chair, 19th century, Angola. Copper alloy, animal hide, wood, 263⁄4 x 12 × 151⁄3 in. (67.9 × 30.5 × 39.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Museum Expedition 1922, Robert B. Woodward Memorial Fund, 22.187; Center: Gonçalo Mabunda (Mozambican, b. 1975). Harmony Chair, 2009, Maputo, Mozambique. Welded weapons (handguns, rifles, land mines, bullets, machine gun belts, rocket-propelled grenades), iron alloy, 481⁄16 x 383⁄16 x 2915⁄16 in. (122 × 97 × 76 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Samuel E. Haslett, by exchange; gift of Mrs. Morris Friedsam, Georgine Iselin, and Mrs. Joseph M. Schulte, by exchange; Designated Purchase Fund 2013.26.2. © Gonçalo Mabunda; Right: Cheick Diallo (Malian, born 1960). Sansa Chair, 2012, Bamako, Mali. Steel, nylon, 311⁄2 x 311⁄2 x 357⁄16 in. (80 × 80 × 90 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Mrs. Carl L. Selden, by exchange; gift of Mary Babbott Ladd and Frank L. Babbott, Jr. in memory of their father, Frank L. Babbott; gift of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and Mrs. H. A. Metzger, by exchange; Ella C. Woodward Memorial Fund, John B. Woodward Memorial Fund, and Designated Purchase Fund, 2013.26.1. © Cheick Diallo. (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

African artists have a long history of responding to fresh design concepts, while always revising them to ends both practical and novel. Together, these three works trace the evolution of a single form: first, as an imported idea became African, and then as contemporary artists adapted this African form for a global market.

Most seats in sub-Saharan Africa are low stools, carved from a single block of wood. Yet, as early as the sixteenth century, Portuguese traders and explorers introduced chairs with backs to southern and eastern Africa. Chokwe artists soon began to produce similar chairs, adding sculptural scenes and Chokwe motifs. This wood chair was carved as an object of status for a chief. In fact, none of these three chairs were meant for sitting. Gonçalo Mabunda’s Harmony chair uses decommissioned handguns, bullet belts, and other munitions collected from the estimated 7 million weapons left in Mozambique following the end of its civil war in 1992. Its design references a coastal East African tradition of high-backed chairs that were symbols of power and prestige, discussion and debate. The Sansa chair, an inventive deconstruction of the chair form, is among the original creations that have established Cheick Diallo as one of Africa’s leading contemporary designers. Built at Diallo’s direction by artisans from Bamako, the half-reclining Sansa chair seems to sit midway between a European notion of the chair as a leisure object and a West African idea of the chair as a support for displaying a person of status.

Left: Owusu-Ankomah (Ghanaian, born 1956, lives and works in Germany). Looking Back Into the Future, 2008, Bremen, Germany. Acrylic on canvas, 591⁄16 x 783⁄4 in. (150 × 200 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Stewart Smith Memorial Fund, 2014.32.1. © Owusu-Ankomah; Right: Unidentified Napatan Period artist, reign of Senkamanisken, circa 643–623 B.C.E. Shabti of Senkamanisken, Nuri, Northern state, Sudan. Steatite, 89⁄16 x 211⁄16 x 115⁄16 in. (21.7 × 6.9 × 5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, by exchange, 39.5. (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

Both of these works, separated by many centuries, use the human body as a platform for expressing and displaying script.

Shabtis are funerary figures intended to do the agricultural work the gods might require of the deceased, represented here holding hoes. The hieroglyphic inscription on this figure is a spell from the Book of the Dead, asking the shabti to do the Nubian king Senkamanisken’s work for him in the afterlife. Owusu-Ankomah’s paintings depict a spiritual world occupied by people and symbols. The male figure in this work is covered by, and moves within, Akan adinkra symbols from the artist’s native Ghana, each of which graphically represents a particular concept or proverb. Looking Back Into the Future depicts a nude man with his head turned backward, in a pose associated with the Akan proverbial concept of sankofa (“one must know the past to know the future”).

Left: Owusu-Ankomah (Ghanaian, born 1956, lives and works in Germany). Looking Back Into the Future, 2008, Bremen, Germany. Acrylic on canvas, 591⁄16 x 783⁄4 in. (150 × 200 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Charles Stewart Smith Memorial Fund, 2014.32.1. © Owusu-Ankomah; Right: Unidentified Napatan Period artist, reign of Senkamanisken, circa 643–623 B.C.E. Shabti of Senkamanisken, Nuri, Northern state, Sudan. Steatite, 89⁄16 x 211⁄16 x 115⁄16 in. (21.7 × 6.9 × 5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, by exchange, 39.5. (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

Both of these works, separated by many centuries, use the human body as a platform for expressing and displaying script.

Shabtis are funerary figures intended to do the agricultural work the gods might require of the deceased, represented here holding hoes. The hieroglyphic inscription on this figure is a spell from the Book of the Dead, asking the shabti to do the Nubian king Senkamanisken’s work for him in the afterlife. Owusu-Ankomah’s paintings depict a spiritual world occupied by people and symbols. The male figure in this work is covered by, and moves within, Akan adinkra symbols from the artist’s native Ghana, each of which graphically represents a particular concept or proverb. Looking Back Into the Future depicts a nude man with his head turned backward, in a pose associated with the Akan proverbial concept of sankofa (“one must know the past to know the future”).

Left: Magdalene Anyango N. Odundo (British, born 1950, Kenya). Vessel, 1990, Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom. Ceramic, slip, 16 × 10 × 10 in. (40.6 × 25.4 × 25.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased with funds given by Dr. and Mrs. Sidney Clyman and the Frank L. Babbott Fund, 1991.26; Right: Unidentified Nok culture artist, circa 550–50 B.C.E. Male Head, Kaduna, Plateau or Nassarawa state, Nigeria. Terracotta, 12 × 71⁄2 x 91⁄2 in. (30.5 × 19.1 × 24.1 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Lisa and Bernard Selz, exhibited through the generosity of the National Commission for Museums and Monuments of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, TL2005.62. (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

While these works appear quite different on the surface, both are made from the same material, terracotta. They were also created through very similar techniques, in which the artist built up the form from thin coils of clay to produce a hollow vessel that could be further sculpted and fired.

The head from the Nok culture is an archaeological fragment, possibly once part of a full figure. One of the oldest pieces in the African collection, it was found at one of the earliest known iron-smelting sites in Africa. Magdalene Odundo, a contemporary artist drawing on the global history of pottery, used an understated anthropomorphic vocabulary to create this abstract, burnished vessel that evokes the female form. Odundo achieved the black, smoky finish by covering her pots with a clay slip and firing them in a closed kiln with combustible materials such as wood chips. Since pottery has long been associated with women’s work across the African continent, some scholars have speculated that female artists created the ancient Nok statuary. It is thus possible that the two works displayed here—among the collection’s oldest and newest, respectively—may both be by women artists.

Left: Magdalene Anyango N. Odundo (British, born 1950, Kenya). Vessel, 1990, Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom. Ceramic, slip, 16 × 10 × 10 in. (40.6 × 25.4 × 25.4 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased with funds given by Dr. and Mrs. Sidney Clyman and the Frank L. Babbott Fund, 1991.26; Right: Unidentified Nok culture artist, circa 550–50 B.C.E. Male Head, Kaduna, Plateau or Nassarawa state, Nigeria. Terracotta, 12 × 71⁄2 x 91⁄2 in. (30.5 × 19.1 × 24.1 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Lisa and Bernard Selz, exhibited through the generosity of the National Commission for Museums and Monuments of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, TL2005.62. (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

While these works appear quite different on the surface, both are made from the same material, terracotta. They were also created through very similar techniques, in which the artist built up the form from thin coils of clay to produce a hollow vessel that could be further sculpted and fired.

The head from the Nok culture is an archaeological fragment, possibly once part of a full figure. One of the oldest pieces in the African collection, it was found at one of the earliest known iron-smelting sites in Africa. Magdalene Odundo, a contemporary artist drawing on the global history of pottery, used an understated anthropomorphic vocabulary to create this abstract, burnished vessel that evokes the female form. Odundo achieved the black, smoky finish by covering her pots with a clay slip and firing them in a closed kiln with combustible materials such as wood chips. Since pottery has long been associated with women’s work across the African continent, some scholars have speculated that female artists created the ancient Nok statuary. It is thus possible that the two works displayed here—among the collection’s oldest and newest, respectively—may both be by women artists.

Left: Unidentified Sapo artist. Mask (Gela), 20th century, Sinoe or Grand Gedeh county, Liberia. Wood, metal, cowrie shell, pigment, animal teeth, antelope and duiker horn, boar tusk, plant fibers, textile, earth, ceramic. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Gordon Douglas III and Dr. and Mrs. Milton Gross, by exchange, 2013.61.1; Right: Unidentified Bamileke artist. Kuosi Society Elephant Mask, 20th century, Grassfields region, Cameroon. Cloth, beads, raffia, fiber, 563⁄4 x 211⁄2 in. (144.1 × 54.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Frieda B. and Milton F. Rosenthal, 81.170. (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

Masquerade is performance art. The works on view here were not meant to be seen as isolated sculptural forms but were part of a whole that included costume, music, songs, food, audience interaction, and, above all, movement. Masked performances have a variety of purposes. These particular masks were both performed to support political authority, but in different contexts.

The Bamileke masquerade is an assertive but controlled and dignified performance worthy of a royal court. The elite Kuosi masking society controls the right to own and wear elephant masks, since both elephants and beadwork are symbols of political power in the kingdoms of the Cameroon grasslands. The Kuosi society assists the king, or fon, in his role as preserver and enforcer of a rigid sociopolitical hierarchy. The very rare Sapo mask would have been used in a performance enacting a terrifying force from the forest. In a society historically without kings or centralized states, the mask may have exerted the will of village elders by imposing economic prohibitions or organizing hunting parties to provide for and protect the village.

Left: Unidentified Sapo artist. Mask (Gela), 20th century, Sinoe or Grand Gedeh county, Liberia. Wood, metal, cowrie shell, pigment, animal teeth, antelope and duiker horn, boar tusk, plant fibers, textile, earth, ceramic. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Gordon Douglas III and Dr. and Mrs. Milton Gross, by exchange, 2013.61.1; Right: Unidentified Bamileke artist. Kuosi Society Elephant Mask, 20th century, Grassfields region, Cameroon. Cloth, beads, raffia, fiber, 563⁄4 x 211⁄2 in. (144.1 × 54.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Frieda B. and Milton F. Rosenthal, 81.170. (Photos: Brooklyn Museum)

Masquerade is performance art. The works on view here were not meant to be seen as isolated sculptural forms but were part of a whole that included costume, music, songs, food, audience interaction, and, above all, movement. Masked performances have a variety of purposes. These particular masks were both performed to support political authority, but in different contexts.

The Bamileke masquerade is an assertive but controlled and dignified performance worthy of a royal court. The elite Kuosi masking society controls the right to own and wear elephant masks, since both elephants and beadwork are symbols of political power in the kingdoms of the Cameroon grasslands. The Kuosi society assists the king, or fon, in his role as preserver and enforcer of a rigid sociopolitical hierarchy. The very rare Sapo mask would have been used in a performance enacting a terrifying force from the forest. In a society historically without kings or centralized states, the mask may have exerted the will of village elders by imposing economic prohibitions or organizing hunting parties to provide for and protect the village.

Double Take: African Innovations

October 29, 2014–March 19, 2017

Celebrating Africa’s continual dynamism and long tradition of artistic creativity, Double Take: African Innovations opens the doors to our storied African collection with a new, experimental installation that invites surprising and unexpected ways of looking at African art. It suggests universal themes that link seemingly dissimilar works, often across vast distances of time and space, while also presenting them within their own specific context of history and place.

In the main Double Take gallery, nearly forty objects, including a number of recent acquisitions, are organized into fifteen pairs or small groups that explore themes, subjects, and techniques that recur throughout African history, including performance, portraiture, the body, power, design, satire, and virtue, among others. A deeper look into our extensive African holdings can also be found in an adjacent “storage annex” display of an additional 150 African masterpieces, with an area for making new connections and responding to the works, including suggestions for other themes. These responses will help shape a case with regularly changing objects, and will also inform the larger presentation of our African collection in the years to come.

A temporary installation planned amid an extensive renovation of our first floor, Double Take: African Innovations is the next phase in the ongoing expansion of our African collection. It builds upon the previous installation, African Innovations, our first chronological African presentation, by exploring further connections between African artworks.

Double Take: African Innovations is organized by Kevin Dumouchelle, Associate Curator, Arts of Africa and the Pacific Islands, Brooklyn Museum.