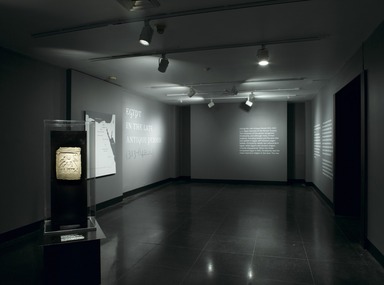

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_01_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_02_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_03_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_04_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_05_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_06_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_07_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_08_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_09_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_10_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_11_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_12_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_13_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_14_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_15_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_16_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture, February 13, 2009 through May 10, 2009 (Image: DIG_E2009_Unearthing_the_Truth_17_PS2.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2009)

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt's Pagan and Coptic Sculpture

-

Egypt in the Late Antique Period (313–642 C.E.)

During the Late Antique Period (313–642 C.E.), Egypt was part of the Roman Empire. The emperors of this period recognized Christianity, and although many of their subjects, including Greeks and Romans who had settled in Egypt, still followed pagan beliefs, Christianity rapidly won adherents in Egypt—while Egypt’s own ancient religion virtually disappeared. When the Arabs conquered Egypt in 642, Christianity was the most important religion in the land. The new rulers brought with them the Muslim faith, which remains the dominant religion of Egypt to this day.

Egyptian Christians, both ancient and modern, are called Copts. For that reason, the period when Christianity became dominant in Egypt is often called the Coptic Period. However, that term overlooks the importance of pagan culture and particularly pagan influence on Coptic art. Thus it seems preferable to refer to this time as the Late Antique Period.

The funerary sculpture in this exhibition comes from cemeteries of towns that were part of the Roman administration of Egypt. Some of these towns were newly founded, while others were old settlements with new Roman names. On the labels for individual objects, their sources, where known, are listed under the names most commonly used today. On the map here, both the modern and the Roman names of towns are shown.

-

The Late Antique Monuments

The first Late Antique Period tombs in the major cemeteries of Egypt were made for people who followed pagan beliefs. Increasingly, however, the same types of tombs were made for Christians, and eventually older monuments that had fallen into disuse were sometimes reused.

The main decoration of many pagan tombs was an image of the deceased, carved almost in the round and facing forward, often within a rectangular niche. Many tomb chapels featured an arch set into the wall above head height that bent forward over the visitor. In pagan tombs, these arches featured representations of mythical figures intended to symbolize the deceased. Thus, the god of the Nile could remind tomb visitors of a mature, successful father; a nymph might stand for a young, unmarried woman; Hercules could symbolize strength or leadership. In Christian tombs, arches also bent out over the visitor, but they were decorated with crosses. Both pagan and Christian tombs were also decorated with plant and animal forms, often arranged in friezes.

Representations of the Virgin and Christ child seem to have been especially frequent in churches and monasteries. A few reliefs in the Brooklyn Museum collection, such as the bust of a saint, also seem more appropriate for religious structures than for individual tombs. Much of the surviving decoration from these buildings consists of architectural elements, like the small column capital in this exhibition.

-

The Modern Forgeries

We now know that the many Late Antique Egyptian sculptures that appeared on the art market in the 1960s and 1970s included a number of modern forgeries. At that time, however, this material was so little known that the bad pieces were not recognized. Only at the end of the 1970s did scholars begin to point out problems of authenticity in some of the material. By that time, the Brooklyn Museum, like many other museums, had acquired both genuine examples of Late Antique Egyptian sculpture and modern imitations.

One reason that the false pieces were so readily accepted may have been that they seemed to have much in common with the genuine examples, many of which had been made to look almost new, with patches of old paint removed and minor surface damages smoothed away. In a few cases, important areas had been entirely recarved and repainted, as can be seen in this exhibition on the face and hands of a red-robed boy standing in a niche. Some badly damaged examples had been extensively recarved. And since some of the forgeries were in all likelihood carved from the badly damaged remains of ancient sculptures, it seems certain that both those who “renewed” the ancient examples and those who created the new versions were working in the same place, quite possibly at one or more of the ancient cemeteries where such material was found.

-

December 4, 2008

An exhibition of thirty works from the Brooklyn Museum’s permanent collection of Late Antique Egyptian stone sculptures (395–642 A.D.) that includes several examples of reworked or repainted works and some that appear to be modern forgeries, will be on view beginning February 13, 2008.

These ancient sculptures were carved from a soft Egyptian limestone and feature both pagan and Christian scenes and symbols. Some were tomb portraits of the deceased, other carvings decorated the tomb and were used in pagan and Christian cemeteries and in Christian churches and monasteries. The term Coptic, which describes some of the pieces, denotes the main and original branch of Christianity in Egypt.

Late Antique Egyptian sculpture was little known when it began to appear on the market shortly after World War II and into the 1960s and 1970s. At that time a number of pieces were acquired by the Brooklyn Museum. Gradually some scholars began to realize that the examples now in museums in both Europe and the United States included many modern imposters, but a comprehensive study has yet to be undertaken. Many experts believe that some of the forgeries were created upon remnants of ancient pieces and that very few pieces remain as they were originally produced in the period.

For a review of the Brooklyn Museum’s pieces, Curator of Egyptian Art Edna R. Russmann joined a number of outside authorities on Coptic art and on the sources of Egyptian stone. Much of that work is still ongoing. This exhibition focuses on the work done so far, and especially on the stylistic characteristics of the works, both ancient and modern.

The examples of the modern imitations are quite ambitious in scale and complexity and often depict unusual subjects and themes. Among the forgeries on view will be a female bust purporting to be Holy Wisdom holding an orb and staff; a limestone relief of the paralytic healed by Christ; and a sculpture depicting the Holy Family. What is striking about the fakes is that they place a greater emphasis on Christian iconography than the authentic works—a reflection of market demand for such imagery in Europe and North America.

The authentic sculptures include the bust of an unnamed Christian saint with a halo and holding a cross; part of a funerary relief representing the Nile god with his consort, the Earth goddess; and a funerary stela made for a three-year-old boy, the son of a Roman soldier who was stationed in Egypt.

The exhibition’s curator, Edna. R. Russmann, states, “It is my hope that by displaying the fakes alongside the genuine works, visitors will gain an understanding into how museums authenticate their collections and gain a better appreciation of the real Coptic art.”

Unearthing the Truth: Egypt’s Pagan and Coptic Sculpture is organized by Edna R. Russmann, Curator of Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Middle Eastern Art, Brooklyn Museum.

A variety of public programs will be presented in conjunction with the exhibition. For more information visit www.brooklynmuseum.org.

View Original