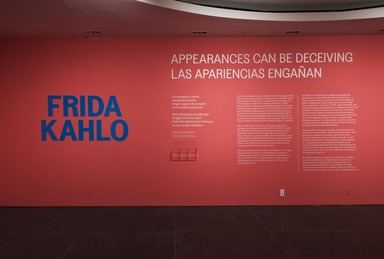

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_01_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

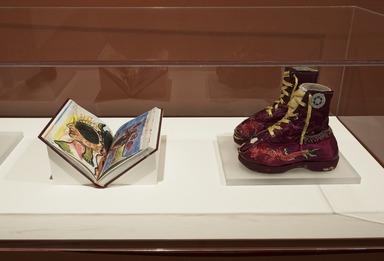

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_02_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

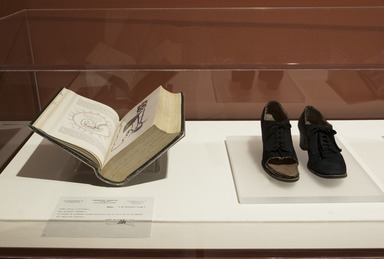

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_03_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_04_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_05_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_06_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_07_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_08_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_09_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_10_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_11_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_12_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_13_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_14_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_15_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_16_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_17_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_18_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_19_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_20_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_21_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_22_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_23_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_24_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_25_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_26_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_27_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_28_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_29_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_30_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_31_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_32_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_33_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_34_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_35_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_36_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_37_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_38_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_39_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_40_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_41_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_42_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_43_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_44_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_45_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_46_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_47_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_48_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_49_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_50_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_51_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_52_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_53_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_54_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_55_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_56_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_57_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_58_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_59_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_60_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_61_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_62_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_63_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_64_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, May 12, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Frida_Kahlo_65_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving

-

DISCAPACIDAD Y CREATIVIDAD

“A pesar de mi larga enfermedad, tengo alegría inmensa de VIVIR”.

El grave accidente que casi le cuesta la vida a Frida Kahlo en 1925 a la edad de dieciocho años, puso fin a sus estudios académicos y a su sueño de convertirse en doctora. Durante el proceso de recuperación, que requirió prolongados períodos de inmovilidad, empezó a pintar, utilizando un caballete plegadizo de madera y un espejo instalado en el dosel de su cama de cuatro pilares. El autorretrato se convirtió en el foco principal de su arte. Dijo: “No estoy enferma, estoy rota”, y añadió, “pero estoy feliz de estar viva mientras pueda pintar”.

Kahlo fue sometida a numerosas operaciones a lo largo de los años en México y Estados Unidos, y las relaciones que mantuvo con doctores, tales como el Dr. Juan Farill en la Ciudad de México, fueron importantes para ella: “He estado enferma un año. Siete operaciones en la columna vertebral. El doctor Farill me salvó. Me volvió a dar alegría de vivir. Todavía estoy en la silla de ruedas, y no sé si pronto volveré a andar. Tengo el corsé de yeso que a pesar de ser una lata pavorosa, me ayuda a sentirme mejor de la espina”. Utilizó varios corsés ortopédicos hechos de cuero, acero y yeso. Kahlo decoró y adornó sus aparatos de soporte y los incorporó a sus pinturas, convirtiéndolos en obras de arte.

En su pintura La columna rota (1944; ver fotografía), Kahlo se representa a sí misma con astucia desafiante, una columna clásica en ruinas pero aún en pie ocupa el lugar de su espina dorsal y ella lleva un corsé ortopédico similar a uno en exhibición cerca de aquí.

El lenguaje y la terminología acerca de la discapacidad han cambiado significativamente desde el tiempo en que vivió Kahlo. Una serie de textos en las paredes de esta exposición vinculan su voz a ideas sociales contemporáneas sobre la discapacidad.

-

NEW YORK EXHIBITION

“You cannot imagine how interesting this city is!”

Although she was scathingly critical of Gringolandia, Kahlo adored New York. In the early 1930s, she fell in love with the city on her first visit. In 1938 she returned to New York triumphantly, as an artist in her own right, exhibiting in her first solo show, at the Julien Levy Gallery on East Fifty-seventh Street.

Delighted, Kahlo wrote a friend: “Everything has been arranged absolutely marvelously. . . . The whole gang here is very fond of me. . . . The gallery is swell and they arranged the paintings very well. Did you see Vogue?”

Time magazine also reviewed her show, saying: “Flutter of the week in Manhattan was caused by the first exhibition of paintings by famed muralist Diego Rivera’s German-Mexican wife, Frida Kahlo. Too shy to show her work before, black-browed little Frida has been painting since 1926, when an automobile smashup put her in a plaster cast, ‘bored as hell.’”

Although the review may seem patronizing and offensive to readers today, Kahlo was thrilled, and she regarded her artistic debut as immensely successful.

-

MODELAR EL GÉNERO

“He roto muchas normas sociales”.

A pesar de ser conocida por sus autorrepresentaciones como una icónica mujer tehuana, Kahlo elaboró y performatizó versiones alternas de sí misma. Se concentró en su vestuario, peinados y accesorios para construir complejas—y por momentos contradictorias—identidades, incluyendo su género. Kahlo gozó de relaciones sexuales con hombres y mujeres a lo largo de su vida. Si bien fue discreta en cuanto a sus relaciones con mujeres, la propia Kahlo confi rmó haber tenido una relación de juventud con una profesora.

En una foto convencional de familia tomada por Guillermo Kahlo en 1926 en la Casa Azul, una Kahlo de diecinueve años encarna un inusual personaje masculino: ostenta un traje de hombre de tres piezas (ver fotografía). En numerosos autorretratos subsiguientes, la artista pintó meticulosamente su oscuro vello facial, para llamar la atención sobre lo que ella consideraba ser sus rasgos masculinos o andróginos. Dijo: “Del sexo opuesto, tengo el bigote y, en general, la cara”.

En términos contemporáneos, diríamos que Kahlo rechazaba las categorías binarias y asumía la fl uidez de género. Pero el lenguaje y las opciones de identidad disponibles en su época con relación a su género y su sexualidad eran muy diferentes a los de hoy.

-

FASHIONING GENDER

“I have broken many social norms”

Although best known for her elaborate self-presentations as an iconic Tehuana woman, Kahlo also constructed and performed alternative versions of herself. She focused on her clothing, hairstyling, and accessories to fashion diverse, complex—and at times contradictory—identities for herself, including her gender. Kahlo enjoyed sexual relationships with both men and women throughout her life. Although she was discreet about her relations with women, she confirmed an early relationship with a teacher.

In a conventional family photograph taken by Guillermo Kahlo in 1926 at the Blue House, nineteen-year-old Kahlo flaunts an unconventional male persona, donning a man’s three-piece suit (see photograph). In numerous subsequent self-portraits, the artist meticulously painted her dark facial hair, calling attention to what she considered her masculine or androgynous features, stating: “I have the moustache and in general the face of the opposite sex.”

In today’s terminology, we would say Kahlo rejected binary categories and embraced gender fluidity. But the language and the choices of identity available to her regarding gender and sexuality during her lifetime were vastly different from today’s.

-

DISABILITY AND CREATIVITY

“In spite of my long illness, I feel immense joy in LIVING.”

Frida Kahlo’s near-fatal accident in 1925 at the age of eighteen meant an end to her academic studies and her hopes of becoming a doctor. During a recovery period that necessitated extended periods of immobility, she started to paint, using a folding wooden easel and a mirror set into the canopy of her four-poster bed. Self-portraiture became the primary focus of her art. She said: “I am not sick, I am broken,” adding: “But I am happy to be alive as long as I can paint.”

Kahlo underwent numerous operations over the years in Mexico and the United States, and her ongoing relationships with doctors, such as Juan Farill in Mexico City, were important to her: “I’ve been sick for a year: 1950–51. Seven operations on my backbone. Dr. Farill saved me by giving me back my joy of living. I’m still in a wheelchair and wearing the plaster corset, which is a terrible nuisance but helps my spine to feel better.” She wore a variety of orthopedic corsets made of leather, steel, and plaster. Kahlo decorated and adorned her support devices, and incorporated them into her paintings—turning them into works of art.

In her painting The Broken Column (1944; see photograph) Kahlo depicts herself as archly defiant, a crumbling but still upright classical column replacing her spine, and she wears an orthopedic corset similar to one displayed nearby.

Language and terminology regarding disability have changed significantly since Kahlo’s lifetime. Wall texts in this exhibition relate her voice to current social ideas about disability.

-

LA CASA AZUL

“Aquí nací”.

Frida Kahlo vivió en la Casa Azul durante la mayor parte de su vida, y ahí murió en 1954. La casa de una planta que construyó su padre en 1904 fue decorada originalmente al estilo europeo burgués, pero cuando Kahlo y Rivera se mudaron allí a mitad de los años treinta, pintaron las paredes de azul vibrante—a tono con el emergente espíritu de orgullo nacional conocido como mexicanidad—y la llenaron de pinturas votivas, hallazgosarqueológicos y arte folclórico mexicano. La Casa Azul se convirtió en un centro neurálgico para las élites artísticas, culturales y políticas, que atrajo a visitantes de todo el mundo.

Puesto que Kahlo estuvo con frecuencia confinada a su casa, transformó la Casa Azul en un microcosmos de México. Árboles de albaricoque, naranja y pinos daban sombra a su jardín. Cultivó flores y vegetales para la mesa. Uno de sus apodos era “Xóchitl”, la palabra náhuatl o azteca para flor. La Casa Azul fue el hogar de sus perros xoloitzcuintli y sus loros, monos y cervatillo.

Según recordó Gisèle Freund acerca de su visita al lugar: “Entramos al jardín repleto de árboles y flores tropicales. Los cactus enredan estatuas y esculturas precortesianas. Una fuente desemboca en una pequeña alberca donde nadan patos. Palomas vuelan en el aire”. -

THE BLUE HOUSE

"Here I was born."

Frida Kahlo lived at the Blue House (La Casa Azul) for most of her life and died there in 1954. The single-story house built by her father in 1904 was originally decorated in a bourgeois European style, but when Kahlo and Rivera moved there in the mid-1930s they painted the walls vibrant blue and—in the spirit ofthe emergent national pride known as mexicanidad—filled it with votive paintings, archaeological finds, and Mexican folk art. The Blue House became a hub for Mexico’s artistic, cultural, and political elite, attracting visitors from all over the world.

As Kahlo was often housebound, she transformed the Blue House into a microcosm of Mexico. Apricot, orange, and pine trees shaded her garden. She grew flowers and vegetables for the table. One of her nicknames was “Xóchitl,” the Nahuatl word for flower. The Blue House was home to her xoloitzcuintli dogs and her parrots, monkeys, and pet fawn.

As the photographer Gisèle Freund recalled of her visit there: “We enter the garden full of trees and tropical flowers. Cactuses wrap around statues and pre-Cortesian sculptures. A fountain flows into a small pool in which ducks bathe. Pigeons fly in the air.” -

ARTE Y VESTIDO

“Desde las brillantes trenzas de lana que coloca en su cabello negro y el color que imprime a sus mejillas y labios, hasta los pesados collares antiguos mexicanos y los festivos colores de sus blusas y faldas tehuanas, la señora Rivera parece—ella misma—un producto de su arte y, como toda su obra, un producto que ha sido compuesto instintiva y meticulosamente bien”.

—Bertram D. Wolfe, revista Vogue, 1938

A lo largo de su vida, los poderosos autorretratos de Kahlo, las fotografías para las cuales posó cuidadosamente y sus originales vestuarios hicieron las veces de modos complementarios de autocreación artística. De adolescente, se vestía de maneras no convencionales para expresar su individualidad y minimizar su discapacidad, y desde sus veinte años de edad asumió los vestidos tradicionales mexicanos que utilizó por el resto de su vida. Aunque su vestuario combinaba elementos de diferentes regiones y períodos, se sentía particularmente identificada con la cultura y la ropa de las mujeres del Istmo de Tehuantepec en Oaxaca, al sur de México.

Kahlo adoptó las blusas suntuosamente bordadas, las faldas hasta el suelo y los chales tejidos, y adaptó los elaborados peinados para crear su propia y cautivadora versión de la mexicanidad. Igual que los zurcidos, quemaduras de cigarrillo, salpicaduras de tinta, restos de pigmento y brochazos que hoy podemos ver en mucha de su ropa, su vibrante vestuario no era fingido, sino una parte integral de su vida, arte e identidad.

-

Sergei Eisenstein — ¡Qué viva México!

To accompany the exhibition Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, the Russian director Sergei Eisenstein’s monumental film project ¡Que viva México! is shown here in its entirety. Begun in 1930, and conceived as an anthology representing different peoples and aspects of Mexico’s culture and politics, from its earliest history to the Mexican Revolution, the project was never completed.

Initially thinking of it as an apolitical travelogue, Eisenstein shot between thirty and fifty hours of film before production was halted due to missed deadlines and budget overruns. Unable to obtain further funding and facing problems with visas, he was unable to edit the final footage in either the United States or the Soviet Union. Subsequently, the raw footage was edited in several different ways. In 1934, for instance, Upton Sinclair, the original producer, contracted an independent producer-distributor to create a number of discrete shorts from the footage.

It was Eisenstein who proposed the title ¡Que viva México! to Sinclair. Like many European intellectuals at the time, the Russian director saw the Mexican Revolution as an idealistic and monumental world event. With Anita Brenner’s book Idols Behind Altars (1929) as a model for the episodic nature of the film, Eisenstein also credited Diego Rivera, whom he met in Moscow in 1927, for inspiring his interest in Mexico. He wrote, “The seed of interest in that country . . . nourished by the stories of Diego Rivera . . . grew into a burning desire to travel there.” The 1979 version shown here was compiled by Grigori Alexandrov, about a decade after the Museum of Modern Art released the original unedited footage to the Soviet Union. Alexandrov attempted to hew as closely to Eisenstein’s ambitious vision as possible. The narrative unfolds in six parts.

1. Prologue: Begins during the Maya civilization in the Yucatán.

2. Sandunga: Features the Tehuantepec region and follows a narrative of courtship and marriage.

3. Fiesta: Captures a celebration of the Holy Virgin of Guadalupe and bullfighting during the colonial era.

4. Maguey: Develops a narrative of love and revenge against a political backdrop of worker revolt during the rule of Porfirio Díaz.

5. Soldadera: Describes the Mexican Revolution through the experience of female soldiers. (This segment of the film is constructed from still photography, as no footage was shot.)

6. Epilogue: Documents Mexico at the time the film was made and includes a celebration of the Day of the Dead. -

MEXICANIDAD

Frida Kahlo y Diego Rivera llenaron la Casa Azul de antiguas cerámicas mexicanas, esculturas de piedra y arte folclórico, similares a las obras de la colección del Brooklyn Museum en exhibición aquí. Ambos artistas expresaron el orgullo que sentían por su identidad mexicana (su mexicanidad) coleccionando y exhibiendo las grandes tradiciones artísticas indígenas desde la antigüedad hasta el presente. El movimiento nacionalista mexicano que vino después de la Revolución de 1910 – 20, motivó a los artistas mexicanos a redescubrir y preservar sus artes y artesanías nativas, y a desarrollar un arte nuevo y autónomo basado en esta herencia.

La celebración del pasado indígena mexicano que emprendieron Kahlo y Rivera quedó documentada en las numerosas fotografías de ambos junto a su colección. Empezaron coleccionando cerámicas del oeste mexicano en los años treinta, cuando comenzaron las excavaciones de tumbas de fosa en los estados de Colima, Jalisco y Nayarit. Adquirieron máscaras de piedra de Teotihuacán, vasijas mayas y figuritas de cerámica de varias culturas mesoamericanas, muchas de las cuales aparecen representadas en sus pinturas y murales. También coleccionaron arte folclórico hecho en centros productores de cerámica, tales como Talavera, en Puebla, y Tonalá, Jalisco. Su colección cubría las estanterías de la cocina, el comedor y los estudios, y llegó a alcanzar más de 59,000 objetos.

Nancy Rosoff, Andrew W. Mellon Senior Curator, Arts of the Americas, co-curó esta sección de obras históricas de la colección Brooklyn Museum. -

MEXICANIDAD

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera filled the Blue House with ancient Mexican ceramics, stone sculptures, and folk art similar to the works displayed here from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection. Both artists expressed pride in their Mexican identity (mexicanidad) by collecting and displaying the country’s great Indigenous artistic traditions from ancient times to the present. The Mexican nationalist movement, which followed the Revolution of 1910–20, encouraged Mexican artists to rediscover and preserve native arts and crafts, and to develop a new, autonomous art based on this heritage.

Kahlo and Rivera’s celebration of Mexico’s Indigenous past is documented by the many photographs of them taken with their collection. They started collecting West Mexican ceramics in the 1930s, when excavations of shaft tombs began in the states of Colima, Jalisco, and Nayarit. They acquired Teotihuacan stone masks, Maya vessels, and ceramic figurines from various Mesoamerican cultures, many images of which were incorporated into their own paintings and murals. They also collected folk art produced in ceramic centers such as Talavera in Puebla and Tonalá in Jalisco. Their collection covered shelves in the kitchen, dining room, and studios, growing to more than 59,000 objects.

Nancy Rosoff, Andrew W. Mellon Senior Curator, Arts of the Americas, co-curated this section of historical works from the Brooklyn Museum collection. -

ARTE Y REVOLUCIÓN

Los importantes programas de experimentación y reforma de la Revolución mexicana también llegaron hasta el terreno de la cultura. A principios de los años veinte, el Ministerio de Educación reclutó a los artistas más importantes del país para crear una nueva modalidad de arte público, el movimiento muralista mexicano. En 1922 Kahlo se matriculó en la Escuela Nacional Preparatoria, donde estudiaba mientras Rivera trabajaba en su primera comisión. Inteligente y extrovertida, formó parte de un grupo de estudiantes conocidos como los cachuchas, en alusión a las gorras que llevaban puestas, que entraron de lleno en los asuntos políticos e intelectuales de la época.

Los estudios formales de Kahlo terminaron a raíz de su accidente en 1925. Se unió al Partido Comunista siendo adolescente y más tarde conoció a Rivera, a través de la fotógrafa y revolucionaria Tina Modotti. Tres meses después de su boda, Kahlo y Rivera lideraron una marcha a favor del Sindicato de Obreros Técnicos, Pintores y Escultores, junto a sus compañeros muralistas David Alfaro Siqueiros y Xavier Guerrero. Kahlo fue una de las pocas mujeres presentes y se vistió como una camarada comunista, gorra de obrero en mano (ver fotografía). -

ART AND DRESS

“From the bright, fuzzy, woolen strings that she plaits into her black hair and the color she puts into her cheeks and lips, to her heavy Antique Mexican necklaces and her gaily colored Tehuana blouses and skirts, Madame Rivera seems herself a product of her art, and, like all her work, one that is instinctively and calculatedly well composed.”

—Bertram D. Wolfe, Vogue magazine, 1938

Throughout her life, Kahlo’s powerful self-portraits, the photographs for which she carefully posed, and her uniquely composed outfits acted as complementary modes of artistic self-creation. As a teenager, she dressed in unconventional ways to express her individuality and to minimize her disability, while in her twenties she embraced traditional Mexican dress and wore it for the rest of her life. Although her wardrobe mixed elements from different regions and periods, she identified particularly with the culture and clothing of the women of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Oaxaca, southern Mexico.

Kahlo adopted the richly embroidered blouses, floor-length skirts, and woven shawls, and adapted the elaborate hairstyles to create her own mesmerizing version of mexicanidad. As the darning, cigarette burns, ink splashes, traces of pigment, and brushstrokes found on many of her clothes show, her vibrant wardrobe was not staged, but was an integral part of her life, her art, and her identity.

-

EXPOSICIÓN DE NUEVA YORK

“¡No puedes imaginar lo interesante que es esta ciudad!”

Aunque fue mordazmente crítica de Gringolandia, Kahlo adoraba Nueva York. A comienzos de los años treinta, se enamoró de la ciudad en su primera visita. En 1938 regresó triunfante a Nueva York, como una joven artista por derecho propio, para acudir a su primera exposición individual, en la Galería Julien Levy en la calle cincuenta y siete, este de Manhattan.

Encantada, Kahlo escribió a una amistad: “Todo ha sido organizado maravillosamente…todos aquí me aprecian mucho.…La galería es fantástica y organizaron las pinturas muy bien. ¿Viste Vogue?”

La revista Time también reseñó la exposición, así: “El revuelo de la semana fue causado por la primera exposición de pinturas de la esposa germano-mexicana del afamado muralista Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo. Demasiado tímida para exhibir su obra antes, la pequeña Frida de cejas negras ha estado pintando desde 1926, cuando un choque de automóvil la dejó en un yeso, ‘terriblemente aburrida’”.

Aunque la reseña pareciera ser condescendiente y ofensiva para lectores de hoy, Kahlo quedó encantada y consideró que su debut artístico fue un éxito rotundo.

-

Roots

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón was born July 6, 1907, in Coyoacán, formerly a village, today part of Mexico City. Her father, Guillermo Kahlo, was born in Germany in 1872 and emigrated to Mexico when he was eighteen. Her mother, Matilde Calderón y González, was born in the state of Oaxaca, in southern Mexico, in 1876, and was of Indigenous and Spanish descent. While immensely proud of her Mexican roots, Kahlo chose to go by Frida, the name her German father gave her.

In the late 1890s Guillermo Kahlo opened a photographic studio in Mexico City. As Frida Kahlo grew older, she helped her father in his darkroom, and assisted him on photographic assignments, including helping Guillermo, who was epileptic, when he became unwell. She shared her father’s attention to detail, learning to retouch images, prepare glass plates, and take photographs herself. In addition to being a favorite sitter for him, Frida would also have been aware of the significant number of self-portraits her father took. Many of her own later self-portrait compositions retain poses and angles she saw in her father’s work. -

IMAGINANDO MÉXICO

“Yo aquí en Gringolandia me paso la vida soñando en volver a México.... Nueva York es muy bonito y estoy mucho más contenta que en Detroit, pero sin embargo extraño México”.

Un nuevo sentido de orgullo acerca de la multifacética herenciade México, en particular de los muchos pueblos indígenas, emergió de la Revolución mexicana de 1910 – 20, la cual puso fin a una época de dictadura y estableció una república constitucional. Artistas, escritores, fotógrafos y cineastas de todo el mundo llegaron a México como resultado de este período, el llamado “Renacimiento Mexicano”, al tiempo en que nuevos hallazgos arqueológicos dieron lugar a una mayor comprensión de la compleja historia del país.

Muchos artistas y académicos, Kahlo y Diego Rivera entre ellos, se sintieron especialmente atraídos por el Istmo de Tehuantepec en el sur de México. La región estaba considerada como representante de la rica cultura nativa, no corrompida por las conquistas coloniales. Aunque Kahlo nunca visitó el Istmo, adoptó los vestidos de la región como parte de su inconfundible identidad sartorial.

Testigo de la presencia sensacional de Kahlo en Estados Unidos, el fotógrafo Edward Weston escribió: “Vestida con un atuendo nativo … causa mucha emoción en las calles de San Francisco. La gente maravillada se detiene a contemplarla”.

-

PICTURING MEXICO

“Here in Gringolandia I spend my life dreaming of returning to Mexico. . . . New York is very pretty and I’m much happier than in Detroit, but I still miss Mexico.”

A new sense of pride in Mexico’s multifaceted heritage, particularly of its many Indigenous peoples, emerged from the Mexican Revolution of 1910–20, which ended an era of dictatorship and established a constitutional republic. Artists, writers, photographers, and filmmakers from around the world flocked to Mexico in the wake of what was called the “Mexican Renaissance,” while new archaeological discoveries led to a greater understanding of the country’s complex past.

Many artists and scholars, Kahlo and Diego Rivera among them, were particularly attracted to the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in southern Mexico. The region was regarded as representative of a rich native culture, unspoiled by colonialist conquests. Although Kahlo never visited the Isthmus, she adopted the clothing of the region as part of her distinctive sartorial identity.

Witnessing her sensational presence in the United States, the photographer Edward Weston wrote: “Dressed in native costume. . . she causes much excitement on the streets of San Francisco. People stop in their tracks to look in wonder.”

-

RAÍCES

"Soy una mezcla".

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón nació el 6 de julio de 1907, en Coyoacán, antes un pueblo, hoy día parte de la Ciudad de México. Su padre, Guillermo Kahlo, nació en Alemania en 1872 y emigró a México cuando tenía dieciocho años de edad. Su madre, Matilde Calderón y González, nació en Oaxaca, en el sur de México, en 1876, y era de ascendencia indígena y española. Aunque siempre estuvo inmensamente orgullosa de sus raíces mexicanas, decidió usar Frida, el nombre que su padre alemán le puso.

A finales de los años 1890, Guillermo Kahlo abrió un estudio fotográfico en la Ciudad de México. A medida que fue creciendo, Kahlo ayudaría a su padre en el cuarto oscuro y sería su asistente en trabajos fotográficos. También le prestaría ayuda a su padre, que era epiléptico, cuando no se encontraba bien de salud. Tenía en común con su padre la atención al detalle, así que aprendió a retocar imágenes, preparar placas de vidrio y tomar fotografías. Además de ser su modelo favorita, Frida también estaría al tanto de la gran cantidad de autorretratos que su padre tomó. Muchos de sus autorretratos posteriores conservan posturas y ángulos que vio en la obra de su padre. -

Con amistad y cariño nacido del corazón tengo el gusto de invitarte a mi humilde exposición

En 2004 un notable tesoro de objetos personales que pertenecieron a Frida Kahlo fue dado a conocer en su hogar de toda la vida, la Casa Azul, cerca de la Ciudad de México. Sellados por deseo expreso de su esposo, Diego Rivera, después de su muerte en 1954, estos materiales, que incluyen ejemplos excepcionales de su vibrante vestuario, son exhibidos en Estados Unidos por primera vez. Frida Kahlo: Las apariencias engañan presenta parte de estos objetos dados a conocer recientemente, junto a pinturas de la artista, así como fotografías y filmes, y brinda una oportunidad única para examinar los modos en que la política, el género, la discapacidad y la identidad nacional influyeron sobre los diversos modos de creatividad de Kahlo.

Nacida en 1907, Kahlo vivió sus años de formación con la Revolución mexicana (1910 – 20) como telón de fondo, hecho que forjó su compromiso duradero con el comunismo. De hecho, más tarde dirá que nació el mismo año en que comenzó la Revolución. Empezó a pintar en 1925, mientras se recuperaba de un grave accidente de tráfico que le ocasionó discapacidades permanentes. A pesar de que sus pinturas no fueron muy conocidas durante su vida, Kahlo es hoy reconocida como uno de los artistas más importantes e innovadores del siglo XX.

El vestuario de Kahlo muestra cómo construyó su imagen propia, basándose en su compleja herencia cultural, la experiencia de la discapacidad, su visión política y el compromiso apasionado con su país, México. Su modo extraordinario de construir su imagen propia se convirtió en fuente—así como en tema—de su audaz e inquebrantable arte. -

With friendship and affection straight from the heart I have the pleasure to invite you to my humble exhibition

In 2004 a remarkable trove of personal items belonging to Frida Kahlo was brought to light at her lifelong home, the Blue House (La Casa Azul), in Mexico City. Locked away at the instruction of her husband, Diego Rivera, following her death in 1954, these materials—including exceptional examples of her vibrant wardrobe—are displayed here in the United States for the first time. Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving presents a group of these recently revealed items alongside paintings by the artist, as well as photographs and film, providing a unique opportunity to examine the ways politics, gender, disability, and national identity influenced Kahlo’s diverse modes of creativity.

Born in 1907, Kahlo lived her formative years against the backdrop of the Mexican Revolution (1910–20), which shaped her enduring commitment to communism. Indeed, she later claimed to have been born the same year the Revolution began. She took up painting in 1925, while recuperating from a serious traffic accident that resulted in permanent disabilities. Although her paintings were little known during her lifetime, Kahlo is now recognized as one of the most important and innovative artists of the twentieth century.

Kahlo’s wardrobe shows how she constructed her own image, informed by her complex cultural heritage, experience of disability, political outlook, and passionate commitment to her native Mexico. Her unique approach to fashioning her self became a source—as well as a subject—of her bold, uncompromising art. -

MARRIAGE

“I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down. . . . The other is Diego.”

Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera were married in Coyoacán town hall in 1929, when she was twenty-two and he was forty-three. Her parents described it as the union of “an elephant and a dove.” The couple divorced in 1939, then remarried in San Francisco in 1940. Kahlo described their second marriage as celibate, and noted her desire to become financially independent, a goal she never achieved. Their fraught relationship is well documented but, in spite of numerous affairs on both sides, Kahlo remained committed to it.

Kahlo traveled outside Mexico for the first time shortly after her marriage, accompanying Rivera to the United States between 1930 and 19 33. He was a world-renowned artist-celebrity, invited to paint murals in San Francisco, New York, and Detroit, and to mount a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. At the same time, the newspapers of the day described her in patronizing and exoticizing terms, such as: “Frida, Diego’s beautiful young wife, is part of the picture. She wears the native costume, a tight-bodied, full-skirted muslin dress, the classic rebozo draped about her shoulders and a massive string of Aztec beads about her slender brown throat.”

-

ART AND REVOLUTION

“I am a communist being.”

Important national programs of experimentation and reform during the Mexican Revolution extended to culture. In the early 1920s, the Ministry of Education recruited the country’s leading artists to create a new form of public art, launching the Mexican muralist movement. In 1922 Kahlo enrolled in the National Preparatory School, where Rivera was working on his first commission. Intelligent and outspoken, she was part of a group of students, known as the cachuchas after the caps they wore, who were immersed in the political and intellectual issues of the day.

Kahlo’s formal studies ended with her accident in 1925. She joined the Communist Party as a teenager and later met Rivera through the photographer and revolutionary Tina Modotti. Three months before their wedding, Kahlo and Rivera led a march for the Union of Mexican Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors, along with fellow muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros and Xavier Guerrero. One of the few women present, Kahlo was dressed like a communist comrade, worker’s cap in hand (see photograph).

-

GRINGOLANDIA

“A las gringas les gusto mucho y prestan mucha atención a todos los vestidos y rebozos que traje conmigo. Se quedan con la boca abierta cuando ven mis collares de jade y todos los pintores quieren que pose para ellos”.

Los encuentros de Kahlo con Gringolandia (como se refería a Estados Unidos) fueron formativos y complejos. Apreciaba la belleza de San Francisco y de Nueva York, y disfrutaba de la diversidad étnica y la rigueza cultural de ambas ciudades: el barrio chino en San Francisco y Harlem en Nueva York eran sus vecindarios favoritos. Kahlo también conoció a personas fascinantes, muchas de las cuales se convirtieron en sus amigos para toda la vida.

“La ciudad de San Francisco es muy hermosa. . . . Por primera vez vi el océano ¡y me encantó!”En San Francisco, la primera ciudad de Estados Unidos que visitó, Kahlo empezó a moldear su identidad indígena mexicana, diferenciándose de las mujeres locales, a las cuales llamaba “espantapájaros” y “aburridas”.

“Nueva York es sencillamente una maravilla. Es difícil creer que la ciudad fue construida por seres humanos, aparece mágicamente”.En Nueva York, Kahlo reafirmó su compromiso político con el comunismo y con México, y escribió: “Hay tanta riqueza y tanta miseria al mismo tiempo que parece increíble que la gente pueda aguantar una diferencia de clases así y soporte la vida de esa forma, pues hay miles y miles de gentes muriéndose de hambre, mientras por otro lado los millonarios botan millones en estupidez y media”.

“Después de Nueva York esta ciudad me recuerda un ‘basurero’. No me gusta nada.”Kahlo tuvo una estadía muy difícil en la industrial ciudad de Detroit. Si bien describió el tiempo que ahí pasó como una miseria absoluta, su arte se transformó, lo cual supuso un enfoque más audaz a la hora de representar sus propias experiencias de vida.

-

GRINGOLANDIA

“The gringas really like me a lot and take notice of all the dresses and rebozos that I brought with me. Their jaws drop at the sight of my jade necklaces and all the painters want me to pose for them.”

Kahlo’s encounters with Gringolandia (as she called the United States) were formative and complex. She appreciated the beauty of San Francisco and New York, relishing the ethnic diversity and cultural riches of both cities: Chinatown in San Francisco and Harlem in New York were favorite neighborhoods. Kahlo also met fascinating people, many of whom became her lifelong friends.

“The city of San Francisco is very beautiful. . . . For the first time I got to see the ocean and I loved it!”In San Francisco, the first city she visited in the U.S., Kahlo began to fashion her Indigenous Mexican identity, deliberately distinguishing herself from the local women, whom she called “scarecrows” and “dull.”

“New York is simply a marvel. It is hard to believe the city was built by humans, it appears like magic.”In New York, Kahlo reaffirmed her political commitment to communism and to Mexico, and wrote: “There is so much wealth and so much misery at the same time, that it seems incredible that people can endure such class difference, and accept such a form of life, since thousands and thousands of people are starving of hunger while on the other hand, the millionaires throw away millions on stupidities.”

“After New York this city reminds me of a ‘dump.’ I don’t like it at all.”

Kahlo had a very difficult stay in industrial Detroit. While she described her time there as total misery, her art was transformed, resulting in a bolder approach to representing her own life experiences. -

MATRIMONIO

“Yo sufrí dos accidentes graves en mi vida, uno en el que un autobús me tumbó al suelo. . . . El otro accidente es Diego”.

Frida Kahlo y Diego Rivera se casaron en el ayuntamiento de Coyoacán en 1929, cuando ella tenía veintidós años y él cuarenta y tres. Sus padres lo describieron como la unión de “un elefante y una paloma”. La pareja se divorció en 1939, luego se volvió a casar en San Francisco en 1940. Kahlo describió su segundo matrimonio como uno célibe, y señaló su deseo de ser independiente financieramente, objetivo que jamás logró. Las tensiones en su relación han sido ampliamente documentadas, si bien Kahlo se mantuvo comprometida con la misma, a pesar de los numerosos affaires de ambos.

Kahlo viajó fuera de México por vez primera poco después de su boda, acompañando a Rivera a Estados Unidos en los años 1930–33. Él era un artista y personaje de fama mundial, invitado a pintar murales en San Francisco, Nueva York y Detroit, y a tener una exposición individual en el Museo de Arte Moderno. Paralelamente, los periódicos de la época describen a Kahlo con términos paternalistas y exotizantes, tales como: “Frida, la joven esposa de Diego, es parte del panorama. Viste un atuendo nativo entallado, un traje de muselina con faldón completo, el clásico rebozo sobre los hombros y una retahíla de cuentas aztecas sobre su esbelta garganta marrón”.

-

March 1, 2019

The Brooklyn Museum will host its eighth annual Brooklyn Artists Ball, the Museum’s largest annual fundraising event, on Tuesday, April 16, 2019. This year’s Ball will honor groundbreaking visual artist Nick Cave and longtime arts funders Bank of America. Taking place during the run of the critically acclaimed exhibition Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, this year’s event will draw inspiration from the life and work of the iconic Mexican artist. Funds from the event support the Brooklyn Museum’s robust exhibitions and programs.

“We are proud to honor artist Nick Cave this year for his tremendous artistic achievements, which address pressing social issues of our time,” says Anne Pasternak, the Shelby White and Leon Levy Director of the Brooklyn Museum. “We’re also proud to recognize and honor the efforts of our longtime partner, Bank of America, for their leadership in arts funding and initiatives around the globe to preserve visual culture. We’d especially like to highlight the work of Rena M. De Sisto, Bank of America’s Global Executive for Arts & Culture and Women’s Programs, who will be accepting the award on Bank of America’s behalf. De Sisto established the Art Conservation Project, which has funded more than 130 conservation projects in 30 countries—including the restoration of the Assyrian reliefs here at the Brooklyn Museum as well as restoration projects at the Museo Frida Kahlo and Museo Diego Rivera Anahuacalli.”

The Ball will begin at 6:30 pm with cocktails and hors d’oeuvres in the Museum’s Beaux-Arts Court, followed by a seated dinner and dancing. The iconic Beaux-Arts Court will be transformed by visionary event producer David Stark to pay homage to Frida Kahlo’s Mexico, complete with food stations and artist activations.

Dinner guests will enjoy a unique Mexican-inspired menu produced in collaboration with Great Performances, the Museum’s exclusive food service partner, and special guest chefs Carlos Arellano of Park Slope’s Chela, Justin Bazdarich of Greenpoint’s Oxomoco, Nathalia Mendez of the Bronx’s La Morada, TJ Steele of Gowanus’s Claro, and Chef Sue Torres. Guests will also enjoy access to Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving, which opened to the public on February 8, 2019.

After dinner, the Dance Party guests will enjoy special activations and multisensory installations inspired by Frida Kahlo. Taking place for the first time in the Court, the Dance Party will once again feature DJ sets from Brooklyn Museum trustee and music producer Kasseem “Swizz Beatz” Dean, among other special guests. Full lineup to be announced. Dance Party tickets go on sale to the public March 4.

Artists Ball Chairs include Regina Aldisert and Brooklyn Museum trustees Stephanie Ingrassia, Carla Shen, Colleen Tompkins, and Amanda Waldron. Barbara Vogelstein will serve as Honorary Chairman. Host Committee members include Sarah Arison, Jill Bernstein, Jennifer and Steven Eisenstadt, Alyssa Fanelli, Karen Kiehl and Jeanne Masel, Miyoung Lee and Neil Simpkins, Galerie Lelong & Co., Francis Xavier de Mallmann and Natasha de Mallmann, Alex Mondre, Sabrina Merriman Peterson,Tracey Riese, Jessical Sailer Van Lith, Olivia Song, Anne-Cecilie Speyer and Rob Speyer, Cate La Farge Summers and Phillip Summers, and Ellen Taubman.

Nick Cave

Nick Cave is an artist and educator working between the visual and performing arts through a wide range of mediums, including sculpture, installation, video, sound, and performance. His work has been exhibited globally at museums in France, Africa, Denmark, Asia, South America, and the Caribbean. Cave is well known for his Soundsuits, wearable sculptural costumes that obscure race, gender, and class, and allow viewers to look without bias toward the wearer’s identity. Cave has completed multiple self-described "Dream Projects" throughout the United States, Europe, and Africa, including The Let Go at The Park Avenue Armory in New York, Here Hear Chicago on Chicago’s Navy Pier, and HEARD•NY in New York’s Grand Central Terminal.

Cave currently works as a Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He received his M.F.A. from Cranbrook Academy of Art and his B.F.A. from the Kansas City Art Institute.

Bank of America

Each year, Bank of America engages in conservation projects at dozens of institutions and supports over 2,000 visual and performing arts organizations worldwide. The bank has been a lead supporter of exhibitions, conservation efforts, and general operations at the Brooklyn Museum for nearly twenty years. They have supported numerous exhibitions, including Hernan Bas: Works from the Rubell Family Collection (2009), Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera (2010), John Singer Sargent Watercolors (2013), and the current exhibition Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving (2019). They have also spearheaded conservation efforts of important works in the Museum’s collection, which includes a recent conservation gift that supports the complete documentation, cleaning, and remounting of six Assyrian reliefs. These reliefs are part of a larger group of twelve that once decorated the vast palace of King Ashur-nasir-pal II (883–859 B.C.E.) in ancient Assyria, a location now destroyed by ISIS militants. Bank of America has played a crucial role in helping to restore this much-loved treasure in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection.

Rena M. De Sisto will accept the award on the Bank’s behalf. De Sisto is the Global Executive for Arts & Culture and Women’s Programs at Bank of America. Under De Sisto’s leadership, Bank of America has become one of the leading corporate supporters of arts programs around the world. Notably, she created the Bank of America Art Conservation Project, which has funded more than 130 conservation projects in 30 countries. These include the conservation of the Brooklyn Museum’s six Assyrian reliefs and Diego Rivera murals in both Mexico and Detroit, among others. She has also worked with the U.S. Department of State on several programs, leads the company’s partnership with the Foundation for Art & Preservation in Embassies, manages the Bank’s ten-year partnership with American documentary filmmaker Ken Burns, and oversees the Bank’s partnerships with the Smithsonian, which include being a founding member of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative.

De Sisto serves on the boards of the Metropolitan Opera, Theatre Forward, OPERA America, and the Finance and Development Committee of the ALIPH Foundation (International Alliance for the Protection of Heritage in Conflict Areas). She is also a member of the Chairman’s Advisory Committee of the British Museum. She lives in New York City.

About the Brooklyn Museum

The Brooklyn Museum contains one of the nation's most comprehensive and wide-ranging collections, enhanced by a distinguished record of exhibitions, scholarship, and service to the public. The Museum's vast holdings span 5,000 years of human creativity from cultures in every corner of the globe. Collection highlights include the ancient Egyptian holdings, renowned for objects of the highest quality, and the Arts of the Americas collection, which is unrivaled in its diverse range from Native American art and artifacts and Spanish colonial painting to nineteenth- and early twentieth-century American painting, sculpture, and decorative objects. The Museum is also home to the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, which is dedicated to the study and exhibition of feminist art and is the only curatorial center of its kind. The Brooklyn Museum is both a leading cultural institution and a community museum dedicated to serving a wide-ranging audience. Located in the heart of Brooklyn, the Museum welcomes and celebrates the diversity of its home borough and city.

Press Area of Website

View Original -

December 11, 2018

Exhibition includes Frida Kahlo’s clothing and other personal items; key paintings and drawings by the artist; photographs, film, as well as related objects from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection.

Opening February 8, 2019, the exhibition marks the first time that Kahlo’s personal objects from the Blue House, in Mexico City, will be on view in the United States.

Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is the largest U.S. exhibition in ten years devoted to Frida Kahlo, and the first in the United States to display a collection of her personal possessions from the Casa Azul (Blue House), the artist’s lifelong home in Mexico City. The objects, ranging from clothing, jewelry, and cosmetics to letters and orthopedic corsets, will be presented alongside works by Kahlo—including ten key paintings and a selection of drawings—as well as photographs of the artist, all from the celebrated Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection. Related historical film and ephemera, as well as objects from the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive holdings of Mesoamerican art, are also included. Offering an intimate glimpse into the artist’s life, Appearances Can Be Deceiving explores how politics, gender, clothing, national identities, and disability played a part in defining Kahlo’s self-presentation in her work and life.

On view from February 8 to May 12, 2019, Frida Kahlo: Appearances Can Be Deceiving is organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator for the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, and Lisa Small, Senior Curator, European Art, Brooklyn Museum, and is based on an exhibition at the V&A London. The Brooklyn exhibition is organized in collaboration with the Banco de México Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, and The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of 20th Century Mexican Art and The Vergel Foundation.

After Kahlo’s death in 1954, her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, instructed that their personal belongings be locked away at the Blue House, not to be touched until 15 years after Rivera’s death. In 2004, these items were unearthed and inventoried. Making their U.S. debut are more than one hundred of Kahlo’s personal artifacts ranging from noteworthy examples of her iconic Tehuana clothing, contemporary and Mesoamerican jewelry, and some of the many hand-painted corsets and prosthetics used by the artist during her lifetime. Shedding new light on one of the most popular artists of the twentieth century, these objects illustrate how Kahlo crafted her appearance, and shaped her personal and public identity to reflect her cultural heritage and political beliefs while also addressing and incorporating her physical disabilities.

Paintings on view include iconic works such as Self-Portrait with Necklace (1933), Self-Portrait with Braid (1941), and Self-Portrait as a Tehuana, Diego on My Mind (1943), which depicts Kahlo in traditional Tehuana clothing and an elaborate headdress with a miniature portrait of Diego placed squarely above her iconic brow. In addition, the exhibition will feature photographs of Kahlo, including childhood portraits taken by her father, the photographer Guillermo Kahlo; images of the artist and her husband; and intimate studies by many renowned photographers of the period, including Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Lola Álvarez Bravo, Gisèle Freund, Nickolas Muray, and Edward Weston.

To highlight the collecting interests of Kahlo and Rivera, works from the Brooklyn Museum’s Arts of the Americas collection will be featured, including ancient West Mexican ceramics such as a Colima dog sculpture and a pair of Nayarit male and female figures, Aztec sculptures of the Maize Goddess and the Wind God, and early twentieth-century pottery from the ceramic center of Tonalá in Guadalajara, Mexico. The ancient Colima dogs were of particular interest to Kahlo because they depict the Mexican hairless dogs (Xoloitzcuintli) that she loved.

“We are absolutely thrilled to feature such an iconic and globally recognized artist in one of her largest exhibitions in New York City to date. Focused on the life and work of Frida Kahlo, the show comes at an important time, when it is critical to build cultural bridges between the United States and Mexico,” says Anne Pasternak, Shelby White and Leon Levy Director, Brooklyn Museum.

Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator, Brooklyn Museum, says, “Under-recognized in her lifetime, Kahlo has become a feminist icon over the past four decades. The prevailing narrative that women are too often defined by their clothes, their appearance, and their beauty was powerfully co-opted by Kahlo through the empowering and intentional choices she made to craft her own identity. The exhibition is titled after a drawing by Kahlo, in which she makes visible the disability that her striking Tehuana skirts and blouses covered. The show expands our understanding of Kahlo by revealing the unique power behind the ways she presented herself in the world and depicted herself in her art.”

Lisa Small, Senior Curator, Brooklyn Museum, adds, “After our recent Georgia O’Keeffe exhibition, which revealed how that artist’s wardrobe was a carefully considered sign of modernity, it is truly exciting to present this exploration of Frida Kahlo, perhaps the only other artist whose sartorial choices were not only deliberately connected to her personal identity and artistic practice, but also launched her status as an enduring cultural icon.”

The exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum explores Kahlo’s experiences in the United States, and New York City in particular. During this influential time in the artist’s life, she solidified her political allegiances and launched her public career as an artist. In 1931, Kahlo traveled to New York with Rivera, whom she had married in 1929. Rivera had been commissioned to paint a mural at Rockefeller Center, a project from which he was famously fired in 1934 for including an image of Vladimir Lenin, the communist revolutionary and leader of the Soviet Union. As a result of these events, and the significant class disparities she saw first -hand in the United States, Kahlo, who was an active member of the communist party, reaffirmed her political beliefs and was inspired to frame her clothing as overtly political, nationalistic, and in support of the Mexican Revolution. In 1938, the surrealist poet André Breton arranged the artist’s first gallery show in New York, at the influential Julien Levy Gallery. A critical success, her first and only show in New York City launched Kahlo’s career internationally. An iconic color portrait of the artist taken by photographer Nickolas Muray atop a Greenwich Village building in 1939 documents this period in New York.

In her personal life, Kahlo came to define herself through her ethnicity, disability, and politics, all of which were at the heart of her work as an artist. Born to a German-Hungarian father and a half-Spanish, half-indigenous Tehuana mother, Kahlo’s carefully orchestrated personal style made a bold statement about cultural identity, nationalism, and gender. In the years following the Mexican Revolution (1910–20), the celebration of regional diversity became a symbol of national pride. By 1930, Kahlo had famously adopted the traditional colorful dress of the Tehuana region, a matriarchal society in Oaxaca, Mexico, which Kahlo revered for the beauty of its culture and the power it entrusted to women. The Tehuana women’s floor-length skirts, billowing blouses, and elaborate headwear became Kahlo’s sartorial signature, and served as a way to reaffirm her political beliefs and pride in Mexican culture, particularly in the 1930s as her politics became more radicalized. The Brooklyn Museum presentation will feature a selection of ensembles from the artist’s wardrobe, many of which she acquired from indigenous vendors in the markets of Mexico City.

Kahlo’s choice of clothing, though a purposeful statement of her politics, must also be understood in relationship to her well-documented disabilities. At eighteen, after recovering from a childhood case of polio that left one of her legs permanently weakened, Kahlo was in a horrific bus accident that left her with lifelong injuries, including a severely broken spine. Enduring more than thirty operations during her lifetime, Kahlo convalesced at the Blue House and in hospitals on and off for decades. The traditional Tehuana clothing Kahlo adopted allowed the artist to control how people saw her, while simultaneously accommodating her physical disabilities under long skirts and loose-fitting blouses. These same disabilities were a significant aspect explored in her artwork. Included in the exhibition is the arresting color drawing, which bears the titular text “Las apariencias engañan” (Appearances can be deceiving). In the self-portrait, Kahlo’s fractured body, typically hidden beneath her clothing, is visible via a transparent blouse and skirt.

Press Area of Website

View Original