Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_01_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_02_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_03_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

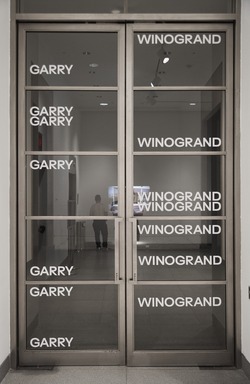

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_04_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_05_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_06_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_07_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_08_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_09_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_10_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_11_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_12_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_13_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_14_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_15_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_22_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_23_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_24_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_27_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color, Friday, May 03, 2019 through Sunday, December 08, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Winogrand_28_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Garry Winogrand: Color

-

COLOR

Garry Winogrand (American, 1928–1984) is one of the most influential photographers of the twentieth century, celebrated for his black-and-white images that pioneered a “snapshot aesthetic” in contemporary art. Yet, since his untimely death at the age of fifty-six, his overall body of work remains incompletely explored, including the 45,000 color transparencies he made between the early 1950s and the late 1960s. This is the first exhibition dedicated to the artist’s color photographs, comprising more than 450 rarely or never-before seen color slides that demonstrate the artist’s commitment to the medium for nearly twenty years.

Garry Winogrand: Color presents the color work in eight sections that highlight Winogrand’s diverse subjects and varying approaches to color photography. Starting with the artist’s photographs at Coney Island in the mid-1950s, the exhibition expands to encompass his exuberant pictures of New York City streets, striking portraits and still lifes, and scenes of everyday life taken on the road during the 1960s—on highways, in suburbs, and at airports, fairgrounds, and national parks. Later sections explore Winogrand’s persistent attention to the shifting identities of men and women in post–World War II America.

A first-generation Jewish American from a working-class family in the Bronx, and practicing at a time when photographs had little market value, Winogrand lacked the financial resources to produce prints from his color slides, which could cost many times more than black-and-white prints. Instead, he displayed them as slideshows. He last exhibited his color photographs as a rotating projection in the landmark 1967 exhibition New Documents at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Around the same time, Winogrand began experimenting with 8mm color motion-picture film. Selections are on view here, underscoring the artist’s continued interest in color and moving images.

Winogrand started using Kodachrome color slide film in the early 1950s as a photographer for magazines like Collier’s and Sports Illustrated, and a selection of these publications is on view. Simultaneously, he found ways to use color as an artistic tool, transforming the commercial and amateur uses of the medium and producing candid pictures that pushed the limits of recognizable fine art photography at the time. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, he would often carry two cameras: one loaded with black-and-white film and the other with color. In a few cases, he raised the color camera just seconds before or after making a now-iconic black-and-white image. On view are twenty-five of his better-known black-and-white photographs, drawn from the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive holdings of works by the artist. -

New Documents Exhibition, 1967

The forty slides in this carousel were selected from eighty-three copies of color slides made by Winogrand between November 1966 and February 1967. He chose photographs covering a range of subjects, mostly taken in New York around that time and during his travels across the country in 1964. Winogrand may have produced these duplicates while preparing for the exhibition New Documents, which opened at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, on February 28, 1967, and also featured his peers Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander. The exhibition included a projection of eighty color transparencies, though his installation was removed after the projector malfunctioned, and little is known about its content.

Before the 1970s, exhibitions of color photographs were still relatively rare. It was expensive and difficult to make prints from color film, a likely reason why Winogrand presented the work as a projection. Many artists and critics also rejected the medium because of its associations with picture magazines, advertising, and amateurs. For example, two of Winogrand’s greatest influences, the photographers Walker Evans and Robert Frank, derided the medium in the 1960s: Frank declared, “Black and white are the colors of photography,” and Evans wrote, “Color photography is vulgar.”

Slideshows were a popular way for many people to share their color photographs during this period. Families would gather in darkened living rooms to view snapshots from vacations, birthday parties, and weddings. Simultaneously, the medium began to play an important role in the analysis and distribution of artists’ work, and Winogrand would often present his photographs as slideshows in classrooms and lecture halls. During the 1960s and 1970s, numerous photographers and artists also started using slide projections as art, from performance and Conceptual artists including Ana Mendieta and Robert Smithson to photographers such as Nan Goldin and Helen Levitt. -

2. Early Color, 1950s

Many of Winogrand’s photographs from the 1950s were produced on assignment for magazines such as Collier’s, Pageant, and Sports Illustrated. He photographed actors and musicians, among them Chet Baker, Eartha Kitt, and Marilyn Monroe; nightclubs and music events, notably the Newport Jazz Festival; and various sporting activities, including college football and automobile racing. He also started to photograph for advertising and stock photo agencies, which licensed images of common subjects for commercial purposes. These various types of pictures reflect the dominant applications of color photography, and Kodachrome in particular, during these years, and their prevalence often deterred artists from using the medium. Nevertheless, Winogrand also made photographs for himself—at Coney Island, in the streets, and on trips in the Northeast and across the country—beginning to blur the distinctions between commercial and candid photography. His color photographs during this decade are similar in content and form to his black-and-white work. The slower speed of Kodachrome, however, meant he often favored more static subjects. -

3. In the Streets, 1960s

Winogrand often said that he began to be a serious photographer around 1960. That year he had his first one-person show, and about then he developed his pictorial strategies for photographing in the streets, including his use of a wide-angle lens and a tilted picture plane, where the horizon line is askew. He said of this period, “I began to live within the photographic process.”

With the release of the faster-speed films Kodachrome II (1961) and Kodachrome X (1962), Winogrand also began taking more color photographs of action in the street. He photographed mainly in midtown Manhattan—in the streets, in parks, around office buildings, and in public plazas. His color photographs differed radically from those of commercial and art photographers at the time, who often sensationalized color; Winogrand treated color as just one more element of the picture.

As he stopped working regularly for picture magazines like Collier’s, which closed in 1957, Winogrand increasingly renounced photography’s ability to tell stories and its role in journalism. His pictures are often filled with multiple figures and rarely convey a single narrative. They are captivating both for the subjects in their foreground as well as at their edges. Even when bursting with people, his images often express a sense of isolation, suggesting something darker during the tumultuous decade. -

4. Portraits and Still Lifes, 1960s

While best-known for his use of a wide-angle lens that fills the picture with multiple figures and events, Winogrand also made posed portraits and close-ups of found still lifes. He photographed store windows, individuals on the street, and details of bodies, such as feet and arms. The large number of these types of pictures within his color work might be due to the slow speed of the film. In a 1957 issue of Popular Photography, the photographer wrote the following in response to a question about the use of color film: “The slow speeds of color films and low light intensity situations quite soften force the photographer to choose static situations to photograph.” -

7. Women, 1960s

Around 1960, as his marriage to his first wife, Adrienne Lubow, deteriorated, Winogrand began to photograph women with greater frequency, sand the subject remained a particular fixation until 1965, when he met his second wife, Judy Teller. He photographed women both young and old, alone and in groups, walking in the Garment District, sunbathing on the beach, or gathered at events.

By presenting women’s changing presence in the street and other public spaces, Winogrand recorded some of the most radical of the decade’s transformations. His images document not only the perceptions and assumptions of one particular male gaze, but also the styles, activities, gestures, and power of women in the era of Second-Wave feminism and the sexual revolution.

A collection of Winogrand’s pictures of women was published in 1975 as Women Are Beautiful. The book was both a critical and a commercial failure at the time, and has been the subject of much debate because of what many critics saw to be Winogrand’s voyeurism and insensitivity to the ethos of feminism during the decade. The ability to photograph strangers in the street, as if the photographer were invisible, was itself a privilege afforded mostly to straight white men during Winogrand’s lifetime. -

8. White Masculinity, 1960s

While much critical attention has been given to Winogrand’s pictures of women, he just as frequently photographed men. His subjects were often white men in suits, usually in groups on the street, and cowboys in the American West. The photographer was fascinated with both of these archetypes of masculinity in postwar America, one representing corporate and middle-class conformity and the other, rugged individualism. Winogrand himself became part of the burgeoning middle class in the 1950s, often working for large media corporations. Yet, as an artist and a first-generation Jewish American, he did not always conform to cultural expectations in the United States at the time. In the early 1960s, Winogrand abandoned his career as a magazine photographer in order to pursue his art full-time, and would struggle both financially and in his family life.

Winogrand repeatedly visited Texas, often photographing men wearing cowboy hats at its state fairs, stockyards, and rodeos. He eventually moved to Austin, Texas, in 1973, where he taught photography until 1978. -

Selecting the Color Slides On View

The selection of 35mm color slides in this exhibition grew out of the most extensive examination to date of Winogrand’s color photographs. Working with the Garry Winogrand Archive at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, the Brooklyn Museum helped scan thousands of slides, and the curators reviewed both the physical and digitized images.

Over the course of several years of research and numerous visits to the Archive, the curators made their selection based on multiple factors. In some cases, Winogrand signed, stamped, or marked the cardboard mounts of color slides that interested him. In others, he produced duplicate slides, which are now scattered throughout the hundreds of boxes in his Archive. The curators also closely reviewed Winogrand’s black-and-white prints and contact sheets from the same years, looking for overlaps in subject matter, since he often photographed the same subjects or locations with both color and black-and-white film.

Winogrand’s vast output and archive have made it difficult for historians and curators to grapple with his work. He was extremely prolific, and left behind a large body of “unfinished” work. In addition to 45,000 color slides, there are approximately 6,500 rolls of black-and-white film that he had either never developed or never seen as proof prints and contact sheets. While his limited resources sometimes prevented him from making prints from his negatives, it would seem that Winogrand was also more interested in the process of taking photographs than in editing and printing them. He frequently allowed others to select his photographs for publications and exhibitions. For both his black-and-white negatives and color slides, he often marked images but did not print them. Revisiting this material not only helps us better understand Winogrand’s art but also broadens our understanding of color photography before the 1970s, the decade in which the medium became more widely accepted in the art world. -

1. Coney Island, 1952–58

Shortly after leaving Columbia University in 1951, where he had briefly studied painting, Winogrand began to work as a freelance magazine photographer. He made some of his earliest photographs on the beaches of Coney Island, using both 35mm black-and-white film and color film. His black-and-white photographs from Coney Island were some of his first images to be published and exhibited: a photograph of a couple frolicking in a wave was included in the landmark 1955 exhibition and companion book The Family of Man at the Museum of Modern Art, as well as in a photo essay for Collier’s magazine.

Winogrand used Kodachrome slide film, released by Kodak to consumers in 1936. It was known for its high resolution, brilliant and lifelike colors, and broad tonal range, able to capture the vibrantly clothed crowds at Coney Island. Since the film was not very sensitive to light and thus required relatively slow shutter speeds, Winogrand was likely attracted to Coney Island’s open skies, which provided ample light, as well as the abundance of lounging figures on the beach—bodies at rest, in contrast to hectic action on the street.

Photographing at Coney Island, Winogrand joined a long list of photographers and artists, such as the American painter Reginald Marsh, who had been attracted to its colorful crowds and scenes. During the 1930s and 1940s, it was a favorite location and subject for many members of the New York Photo League, an organization whose photographers were pioneers of street photography in the United States and included several of Winogrand’s friends and mentors. Like him, many of them were immigrants or first-generation Americans, drawn to the diverse populations gathered there. -

5. On the Road, 1960s

In March 1964, Winogrand received his first John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship in Photography, to make “photographic studies of American life.” The prestigious grant allowed him to travel across the country that summer, driving through seventeen states in a 1957 Ford Fairlane. The grant also provided the means to buy and process more color film. Of the 550 rolls of film he used, 100 were Kodachrome. For Winogrand, color film, widely used by commercial and amateur photographers, perfectly documented the industrially manufactured colors of clothes, automobiles, and other consumer goods in postwar American life.

The photographs are observations of a native New Yorker and a first-generation Jewish American who was dazzled by, yet ambivalent about, the rest of the United States, especially following the assassination of John F. Kennedy and in the midst of the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement. In his Guggenheim application, Winogrand expressed his attitude about the country and its representation:

"I look at the pictures I have done up to now, and they make me feel that who we are and how we feel and what is to become of us just doesn’t matter. Our aspirations and successes have been cheap and petty.

I read the newspapers, the columnists, some books, I look at some magazines (our press). They all deal in illusions and fantasies. I can only conclude that we have lost ourselves, and that the bomb may finish the job permanently, and it just doesn’t matter, we have not loved life."

Winogrand attempted to visualize what he thought to be a more honest representation of the United States, photographing isolation, consumerism, gender and racial prejudice, and the military-industrial complex. Yet he managed to find humor, joy, and hope in many of his subjects, whether pictures of teens enjoying a carnival or a couple embracing at a rodeo. -

6. Travel, 1960s

The 1960s witnessed travel on a scale never before seen, and Winogrand took advantage of new modes of transportation to cross the country just as Americans enjoyed new opportunities for domestic vacations. During his numerous trips, he frequently photographed automobiles, boats, and airplanes—symbols of prosperity in the postwar years. He often photographed from his car, focusing his lens on seemingly absurd and sometimes surreal scenes on streets and highways.

Although he was terrified of air travel, Winogrand repeatedly photographed at airports, which were filled with well-dressed crowds. During these years, flying was an aspirational activity, and its glamorous image was reinforced by advertisements, newspapers, and magazines that were full of glossy photographs showing celebrities jetting around the world. Winogrand focused on the more banal moments of air travel, observing how travelers killed time waiting for flights, luggage, and loved ones. -

Winogrand in Black and White

This gallery features twenty-five gelatin silver photographs drawn from the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive holdings of works by Winogrand. The selection highlights the subjects and themes found in his better-known work in black-and-white film, which had a faster exposure time than color, often allowing for more lively scenes in the street or on the road. Winogrand’s use of a wide-angle lens during the 1960s put him seemingly in the center of the field, surrounded by his subjects and events, not just observing them but participating in the action. The skewed horizon and feeling of chaos in many of his pictures belie his careful compositions. Winogrand believed that the act of framing something transformed it: “Photography is about finding out what can happen in the frame,” he said. “When you put four edges around some facts, you change those facts.”

Included are comparative images of some of the 35mm color slides featured in the slideshows in the previous gallery. In some cases, Winogrand shot the same subject or location with both black-and-white and color film. In other cases, the color photographs demonstrate the similarities and differences between his use of both mediums.

-

January 15, 2019

Garry Winogrand: Color sheds new light on the influential career of twentieth-century photographer Garry Winogrand (1928–1984) as the first exhibition dedicated to the artist’s color photographs. While almost exclusively known for his black-and-white images that pioneered a “snapshot aesthetic” in contemporary art, Winogrand also produced more than 45,000 color slides between the early 1950s and late 1960s. The exhibition will feature an enveloping installation of seventeen projections comprising more than 450 rarely or never-before seen color photographs that demonstrate the artist’s commitment to color, with which he experimented for nearly 20 years. Also included are 25 gelatin silver photographs drawn from the Museum’s extensive holdings of works by the artist.

Garry Winogrand: Color is on view from May 3 through December 8, 2019, and is organized by Drew Sawyer, Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography, Brooklyn Museum, with Michael Almereyda and Susan Kismaric. This marks the first exhibition curated by Sawyer as the Brooklyn Museum’s Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Curator of Photography, a new position devoted to the expanded presence of photography at the Museum.

The selection of the slides in this exhibition is the result of the most extensive examination to date of Winogrand’s color photographs. Working with the Garry Winogrand Archive at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, the Brooklyn Museum helped scan thousands of slides, and the curators spent hundreds of hours reviewing both the physical objects and the digitized images. The results of this comprehensive research are presented in eight thematic sections that highlight Winogrand’s diverse subjects and approaches to color photography. Starting with the artist’s earliest experiments with color at Coney Island in the 1950s, the exhibition expands to focus on his exuberant pictures of New York City streets, striking portraits and still lifes, and scenes of everyday life taken on the road during the 1960s, set against the backdrops of highways, suburbs, airports, fairgrounds, and national parks. Later sections explore Winogrand’s persistent focus on gender roles in postwar America. This unprecedented look at Winogrand’s color photography is accompanied by a selection of the artist’s most recognizable black-and-white photographs from the Museum’s collection, including World’s Fair, New York City (1964) and Central Park Zoo, New York City (1967).

“Continuing the Museum’s commitment to canon-expanding exhibitions, Garry Winogrand: Color is an exciting opportunity to rethink not only the work of an influential artist but also the history of color photography and its modes of presentation before 1970,” says curator Drew Sawyer. “Upon his sudden death at the age of 56, Winogrand left behind a prodigious and unresolved estate that is only beginning to be fully explored, as is evident from the numerous exhibitions, books, and even a documentary film on him in recent years. Predicting photographic practices of today, he photographed nearly everything, often leaving the editing of his pictures to others. Building on recent scholarship, this exhibition provides a long-overdue examination of another aspect of Winogrand’s ‘unfinished’ work, which in addition to the 45,000 color slides includes more than 6,000 rolls of unedited black-and-white film.”

Winogrand displayed his color photographs as a slide show in the landmark exhibition New Documents (1967) at the Museum of Modern Art, which also included the work of Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander. The installation of 80 color slides, however, was removed after the projector malfunctioned, and little is known about its content. One of the projectors in the Brooklyn Museum exhibition will feature color slides selected from 83 duplicate slides that Winogrand made between November 1966 and February 1967—possibly images that the artist prepared specifically for New Documents.

Coming from a working-class background in the Bronx and active at the time when photographs had little market value, Winogrand did not have the resources to produce costly and time-consuming color prints. Despite this, he remained committed to the medium, often carrying around two cameras at once: one with black-and-white film and one with Kodachrome color film. Many of his well-known works in black-and-white have accompanying color images, shot just moments apart from each other. While the black-and-white images went on to become celebrated examples of the burgeoning snapshot aesthetic, the color ones were mostly overlooked.

Winogrand began shooting with color film in the early 1950s as a photojournalist for publications like Sports Illustrated and Collier’s, examples of which are included in the exhibition. Eventually, he found ways to use the industrially manufactured color film as an artistic tool, aping the commercial and amateur uses of the medium and investigating the poetic potential of color, resulting in candid images that pushed the limits of recognizable fine art photography at the time. He also worked to instill a greater respect for color photography in future generations of artists. During his time teaching at Cooper Union in New York, he invited fellow color photographers like William Eggleston to lecture. Among his students was Mitch Epstein, who would ultimately follow Winogrand’s advice to use color photography and help further elevate the medium in the coming decades.

The exhibition coincides with the publication of Garry Winogrand: Color by Twin Palms Publishers. Leadership support for this exhibition is provided by the Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Charitable Trust.

We are grateful to the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, Tucson, which houses the Garry Winogrand Archive and whose support made this exhibition possible.

Garry Winogrand: Color

View Original

![[Untitled]](https://d1lfxha3ugu3d4.cloudfront.net/images/opencollection/objects/size0/83.216.21_PS9.jpg)