Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_01_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_02_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_03_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_04_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_05_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_06_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_07_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_08_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_09_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_10_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_11_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_12_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_13_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_14_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_15_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_16_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_17_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_18_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_19_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_20_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_21_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_22_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_23_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_24_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_25_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_26_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_27_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_28_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_29_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_30_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_40_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_41_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_42_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_43_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_44_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_45_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_46_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_47_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_48_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_49_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_50_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_51_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_52_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_53_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_54_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_55_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_56_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_57_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_58_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_59_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_60_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_61_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_62_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_63_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_64_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_65_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_66_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_67_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_68_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_69_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_70_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, Saturday, July 20, 2019 through Sunday, January 05, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2019_Pierre_Cardin_71_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2019)

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion

-

The Palais Bulles

The circle motif that recurs in Cardin’s designs is dramatically explored in the Palais Bulles (Bubble House), the one-of-a-kind home he acquired in the South of France in 1992. The Palais Bulles was commissioned in 1984 by the French industrialist Pierre Bernard and designed by the Hungarian architect Antti Lovag. Suggesting an architectural bubble bath, the Palais Bulles’s contiguous series of round rooms evokes both ancient human caves and dwellings dug into or created from the earth and a futuristic gateway with finished, modern styling.

After Bernard died in 1991, Cardin acquired the unfinished property. For the next fourteen years, he worked in collaboration with Lovag and twelve interior designers to finish the original structure and furnish each room. The Palais Bulles includes ten bedrooms, a panoramic lounge, a reception hall, a 500-seat amphitheater, swimming pools, and waterfalls.

Over the years, the house’s extraordinary shape has made it a sought-after setting for music videos and film shoots. Raf Simons showed his 2016 Dior Resort collection there, placing models against the building’s round windows in a way that recalls Cardin’s own presentations in circular doorways from the late 1960s. -

Maxim's

In 1981 Cardin acquired Maxim’s, the French bistro established in 1893 that became a famed center for high society and great cuisine. The historic restaurant served as a setting for Franz Lehár’s 1905 operetta The Merry Widow and Vincente Minnelli’s 1958 film Gigi, and was a popular dining spot for artists from Jean Cocteau to Maria Callas.

Having successfully marketed his own name, Cardin dotted Maxim’s restaurants around the world, cultivating up-and-coming chefs such as Wolfgang Puck. The Maxim’s moniker was placed on international restaurant destinations, flower shops, food products, and fragrances, each evoking the Belle Époque. Today, the Maxim’s brand continues on extensive lines of chocolates, macarons, savory items, and wine. -

Espace Cardin

In 1969 Cardin purchased the 125-year-old Théâtre des Ambassadeurs in the Champs-Elysées district of Paris. The theater had hosted hundreds of important performances by Josephine Baker, Maurice Chevalier, and others, and theater productions by luminaries such as Jean Cocteau, Federico García Lorca, and Marcel Pagnol.

After lengthy renovations, the building reopened as Espace Cardin, which included a theater, cinema, gallery, and design studio. The space became known for groundbreaking theatrical works, including Robert Wilson’s eight-hour epic, Program Prologue Now: Overture for a Deafman (1971), and performances by actors Marlene Dietrich, Gérard Depardieu, and Russian ballet star Maya Plisetskaya.

In 1970 Cardin also began to show his Spring and Fall collections at the venue, freeing him from the traditional fashion presentation calendar, as well as hosting exhibitions such as Color in the Street (1977), which he co-organized with Jean Joyet. In the space's upper offices, Cardin also maintained a studio where designers such as the young Philippe Starck created new works of couture furniture and industrial design. -

Hats and Helmets

Throughout Cardin’s career, he always looked at every aspect of an ensemble. The hat was an important element, in conversation with the entire silhouette. Cardin’s hats were on trend with fashions of the 1950s, but in the 1960s he introduced new shapes such as the helmet and the “halo” worn with the Cardine dress.

To echo the squared and sculpted shoulders of the 1980s and 1990s, Cardin returned to the helmet. Suggesting medieval armor, hijabs, and burkas, his new designs alluded to headwear that had developed over centuries for protection and anonymity. Often revealing only eyes or a partial face, these bold, modern hats in leather and wool can seem simultaneously historical and very avant-garde. The next phase in Cardin’s hat trajectory was also bold in scale, and often surrealistic. Referencing traditional men’s hats, Cardin created upsized versions in premium wools, with attitude and character, and sometimes a sense of whimsy and élan—a Mad Hatter’s fantasy. -

Circles

Cardin’s interest in geometry has extended throughout his career, beginning when he was an apprentice tailor in his teens. Over the decades, his work has featured triangular lamps and square shoulders, but it is the circle that predominates. “Porthole” dresses with circular breast rings; hats and eyewear; vinyl necklaces and wool skirts with circular lobes; parabolic hems and sleeves; and circular furniture—all have been based on circle motifs. This is perhaps natural, given that clothes encircle the body in tubes and round openings at the neckline, armholes, wrists, waistline, and ankles. Cardin’s cylinder suits with “tube” pants from the early 1960s and his Pop art masterpiece known as the “target minidress” from 1966 (displayed earlier in the exhibition) predate the more recent examples of circle designs on view here. -

Parabolas

Technically, a parabola is a symmetrically mirrored U-shape. Cardin began working with the parabola in the 1950s, particularly in the 1957 “Lasso” collection. With the introduction of stretch fabrics and hoops in the 1960s, those sweeping, graceful parabolic drapes became amplified, evolving into ellipses and cones.

Some of Cardin’s “Parabolic” fashions collapse flat, are easily packed, and emerge as before—like his earlier Cardine dresses, which could be twisted, rolled, and stowed effortlessly into luggage. Developed alongside Cardin’s investigations into furniture sculpture, the big, sculptural shapes of the “Parabolic” dresses were likewise designed to be seen in 360 degrees. And since they were made of stretch fabrics, they had a bounce reminiscent of his “Kinetic” dresses from 1972. -

Starry Evening

“I preferred to imagine an evening dress for a world that does not exist yet. I imagined dresses made of crystals and flashing lights.”

—Pierre Cardin, 2019

Cardin’s dreams of space exploration and dress for the future encompassed not only daywear, but evening wear. Since childhood, he had been dazzled by the night sky. Beginning in the 1950s, Cardin’s atelier—distinguished by its impeccably tailored daywear—always featured a broad selection of elegant evening wear and gowns, made from exquisite and newly developed materials. In this gallery we see a constellation of Cardin looks that utilize rhinestones, sequins, and shimmering surfaces, as well as his iconic parabolic forms, to evoke the stars and galaxies of the night sky seen from Earth. -

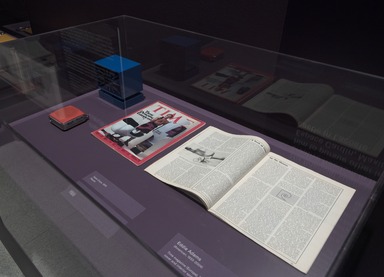

Licensing

Beginning in the late 1960s, in an unexpected move for a couture designer, Cardin began to license his name for a series of products for distribution in quality department-store chains in England, Germany, Japan, and Argentina. Unlike many licensors today, Cardin’s company employed managers who supervised the design and manufacturing of his licensed products, which rose in popularity and exceeded profit margins because of their quality.

As sales of Cardin’s licensed products grew, so did the advertising for them. Each product had a visible Pierre Cardin logo or logotype, and the licensees by agreement also created advertising for the merchandise. In this way, licensing for Cardin was also advertising for Cardin. Over time, Pierre Cardin’s logo and logotype would appear on more than 850 licenses, in over 110 boutiques around the world.

His financial success and independence afforded Cardin creative freedom in his haute couture designs and allowed him to pursue other interests, including the acquisition of Espace Cardin, Maxim’s restaurant, the Palais Bulles, and a castle in Lacoste. -

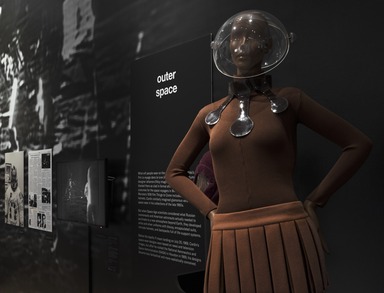

Outer Space

What will people wear on the moon? In Georges Méliès’s 1902 film Le voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon), costume designer Jehanne d’Alcy imagined the group of professors blasted there as clad in formal attire. René Hubert’s costumes for the space voyagers in William Cameron Menzies’s 1936 film Things to Come included spherical glass helmets. Cardin similarly imagined glamorous versions of space wear in his collections of the late 1960s.

But when Space Age scientists considered what Russian cosmonauts and American astronauts actually needed to acclimate to a new atmosphere beyond Earth, they developed white and silver uniforms with blousy, encapsulated suits, intricate helmets, and backpacks full of life-support systems.

Before the Apollo 11 moon landing on July 20, 1969, Cardin's space-wear designs were based on news and television images, but after he visited the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) in Houston in 1969, his designs became less fantastical and more realistically conceived. -

A Future for Everyone

Cardin’s universal “Cosmocorps” fashions, often worn by Japanese model Hiroko Matsumoto, resonated with visions of an inclusive future that were current in Space Age popular culture. In 1966 the television series Star Trek took viewers to outer space—“where no man had gone before”—and featured female and male actors clad in minimalist, unisex suits that resemble Cardin’s designs (see wall mural and adjacent minidress).

Star Trek signaled that the future would be an inclusive one by casting a black actor, Nichelle Nichols, as Lieutenant Uhura and Japanese American George Takei as Lieutenant Sulu (even if the cast's diversity may seem limited by today's standards) and by dressing men and women in unisex clothing. Like Cardin’s unisex styles, William Ware Theiss’s costumes for Star Trek imagined a place where women and men dress similarly and equally, living together in harmony. -

Youth in Central France

Born Pietro Cardin in San Biagio di Callalta, Italy, on July 2, 1922, Pierre Cardin was one of ten children. His mother had been an assistant to an opera singer from Montenegro, and his father and grandfather worked together in the wine and grappa industry. In 1924, fleeing fascism, his family moved to Saint-Étienne, France. A good student, Cardin held various part-time jobs, including one with a local tailor, Louis Bompuis. At the age of eighteen, he left home to pursue his dream of being a couturier.

Making his way first to Vichy, Cardin apprenticed at the tailor Chez Manby for several years. There he learned to cut, trace, and sew, even to hand-sew buttonholes, first learning menswear and then clothes for women. But like other young men of the time, he was called into wartime service, eventually joining the Red Cross, where he studied accounting—a skill that would serve him later. -

"Cosmocorps"

An extension of Cardin’s 1960s “Cylinder” collection for men, the “Cosmocorps” line of clothes took fire after its launch in 1964. A bridge to his later unisex looks of 1968, the “Cosmocorps” line featured collarless and rolled collars, as well as asymmetrically placed zippers. Bodysuits, jumpsuits, and unitards emerged as primary foundation garments for both men and women, over which vests, skirts, codpieces, and jewelry were worn. Fashion-forward and gay men—including writer Truman Capote, artist Salvador Dalí, actor Alain Delon, and American designer Rudi Gernreich—wore the newly minted suit design. -

Kinetic Fashion

Cardin’s “Kinetic” fashions were designed as moving objects, in the spirit of Alexander Calder’s mobiles of the 1930s to 1970s—moving sculptures or mobiles versus traditional static sculptures. Cardin incorporated the movement of the wearer as an aspect of the design, giving the garment the potential to be a mobile or kinetic sculpture.

Some examples include the “Carwash” dress, created from wide loops of fabric that suggest a spinning eggbeater when in motion, and the “Pendulum” dress, composed of circle-ended strips or lobes of fabric that swing out like a flower. Cardin also designed pants “à roulette (little wheels),” where the bottom of the pant leg is rounded and covers the shoe, to give the wearer an appearance of walking on wheels or roller-skating. -

Fashions for Tomorrow

Pierre Cardin is one of the most acclaimed and successful fashion designers and businessmen in France—and the world. A master tailor of haute couture, he risked his career and reputation to launch a ready-to-wear line in 1959. In the process, he democratized fashion, bringing good design to a broader public.

As a businessman, Cardin sought financial independence, because financial independence meant creative independence. More than eight hundred licenses afforded him the freedom to explore interests beyond fashion: theater production, furniture and industrial design, cuisine, architecture, and a vast array of humanitarian efforts.

At ninety-seven, Cardin arrives at the office each morning and continues to design. He remains curious about what’s next, what’s new, and what’s in our collective future. His prediction: “In 2069, we will all walk on the moon or Mars wearing my ‘Cosmocorps’ ensembles. Women will wear Plexiglas cloche hats and tube clothing, men will wear elliptical pants and kinetic tunics.”

Only time will tell. -

twenty-first-century unisex

Cardin’s fresh ensembles from the last decade could be described as “Cosmocorps 2019.” Returning to his early unisex strategies, he has designed miniskirts and minidresses for women and long vests for men—both of similar length. Seen side by side, they suggest that Cardin has realized his once-radical vision of a “future fashion” of equality.

In a veritable lineage of unisex design, his influence can be felt in the work of former employee Jean-Paul Gaultier, in designs of Gaultier’s former assistant Martin Margiela, and in John Galliano’s recent “Co-ed” presentations for Maison Margiela. -

Bold Shoulders

In the 1970s, as pant legs became ample enough to cover a person’s shoes, men’s ties were as wide as their hands, and lapels broadened across the chest, a revival of the bold shoulder began. Some of Cardin’s more noted shoulder designs were introduced after his first trip to China in 1978, when he was inspired to create the “Pagoda” coat and the “Head of the Moon” chest of drawers, both displaying a broad-shouldered silhouette. “Origami” shoulders—which featured complex fabric folding—soon followed, as well as women’s dresses with segmented, parabolic shoulders. Men’s leather jackets featured “American Football” shoulders, which riffed on the scale of football players’ large shoulder pads and the segmented construction of the leather football itself.

These bold and now iconic silhouettes by Cardin (several more examples are on view at the exhibition’s entrance) expanded the vocabulary of the shoulder-padded jackets of the 1940s and took them to extremes. Endowing the wearer with the quality of a superhero in armor, Cardin’s shoulders gave fashion a new, street-tough language. -

Illumination

Cardin’s designs have emitted light through the use of both reflective materials and electric lights. In the works in the adjacent gallery, reflected light or shimmer is realized by means of metallic and mirrored materials such as lamé, rhinestones, sequins, mirrors, and jewelry, creating dynamic or kinetic effects.

Cardin also ventured into the addition of actual lights. In a 1963 episode of the television series The Jetsons titled “Miss Solar System” (see nearby video), Jane Jetson purchases a new gown that has a “novel accessory”: a fifty-dollar extension cord that allows her “Pierre Martian Original” dress to illuminate and blink. This animated fantasy was actually in sync with Cardin’s ideas. He produced his robe electronique in 1968, using small battery-powered lights (see adjacent photograph), and in 2012 he used LEDs to create illuminated line drawings on black jumpsuits and dresses.

Additionally, Cardin created “illumination” or “brightness” effects by using a color vibration technique of placing vivid (often primary) colors against neutral gray or black. In this gallery, a yellow parabolic skirt is set against a gray top, a rainbow apron cascades off a black lace bodice, and a black leather jumpsuit appears to have illuminated piping. These balanced color combinations and proportions create the illusion of “brightness” or neon effects without electricity or reflective materials. -

Couture Furniture and Industrial Design

Cardin began expanding his practice to include industrial design objects (watches, clocks, radios, and lighting) in the 1960s, followed by couture furniture and cars and airplanes.

His first foray into car design was the detailing for the Simca in 1969. For American Motors Corporation’s 1972 Javelin, Cardin designed upholstery and interior door panels, as well as custom auto-body colors, strip detailing, and taillights. In 1979 he designed the interior and exterior of Atlantic Aviation’s Westwind 1124 (echoing a design pattern from a 1967 coat and a 1970 wristwatch). That year he also designed the Phaeton Edition Pierre Cardin Cadillac, available in several colors with his “escargot” (snail) PC logo hubcaps, and in 1981 he redesigned the Cadillac Eldorado Evolution, which featured virgin-wool carpeting, a mahogany and walnut dashboard, two-tone, hand-tooled leather seats, and a thirty-layer lacquer paint finish similar to that of his topline furniture. Cardin’s cars and airplanes were designed, like his couture furniture and “Kinetic” dresses, as 360-degree experiences, to be seen in the round. And like the kinetic fashions, they were also designed to be seen in motion. -

New Materials and the Visible Invisible

Cardin embraced a variety of innovative materials and fabrication techniques in his designs. In 1968 he released a series of 3-D molded dresses made from Cardine, his own Dynel fabric that was three years in development. In addition, he explored other new and unconventional dressmaking materials including plastics, Plexiglas, and vinyl.

Plexiglas, also known as acrylic glass, was viewed as a safer and more lightweight replacement for real glass. With the addition of plasticizers or heat, Plexiglas can be made more pliable and thus molded or cast into shapes such as a helmet, a visor, or even a bandeau (see nearby suit, which also includes a pleated vinyl skirt). Whether used in dresses, visors, or sunglasses, clear plastics are simultaneously visible and not visible, giving an effect that is nude yet not nude. Though never completely “invisible” because of their shine, tint, or edges, clear materials provide protection but are at the same time revealing. -

Gender-released Dressing

Western dress has historically emphasized male-female gender differences. In some areas of the world, long robes, ponchos, capes, and sashes have created a more ungendered visual fashion language, as seen in the robes (jalabiya) worn by both men and women in much of the Middle East, southern Asia, and northern Africa. Similarly, Communist China had its own version of unisex wear: the gray or blue suit.

Cardin and other Western designers such as Rudi Gernreich began showing gender-neutral collections in the 1960s. The “Cosmocorps” collections were Cardin’s earliest investigations into equality dressing, but after the Apollo 11 moon landing, his unisex designs became less purely imaginary and more realistic. Cardin clad the figure in a knit body stocking, form-fitting and adaptable to multiple body shapes, that served as an ungendered foundation garment. He then layered elements such as jewelry, bibs, skirts and aprons, and boots over the bodysuit, in a continuation of his “Cosmocorps” look. Today, cotton T-shirts and sweatshirts, once deemed appropriate only as underwear and gym wear, might be seen as comparable unisex garments. -

Cardin in Cinema

Costumes for balls, galas, and charity events have been an important part of Cardin’s design practice since he opened his first Paris atelier in 1950. At these fashionable but private parties, the costumes were rarely photographed and seen only by those in attendance.

Cardin’s works reached a much larger audience through his work in film. He dressed the renowned French actress Jeanne Moreau for numerous films, including Mata Hari, Agent H21 (1964), in which Moreau plays the famed exotic dancer and accused World War I German spy, and later for the Orson Welles film The Immortal Story (1968), where she dons an updated version of nineteenth-century colonial garb in Macao (China).

Cardin’s contemporary designs were also in demand for stories set in recent times. Moreau sports his current fashions in Bay of Angels (La baie des anges, 1963), and Mia Farrow, for her first starring role in the Cold War thriller A Dandy in Aspic (1968), visited Cardin’s atelier to select her screen wardrobe.

Although most screen costumes are made by costume designers, fashion designers have frequently collaborated with major female film actors as a way to individualize their screen images. Coco Chanel designed costumes for Joan Blondell in Three Broadway Girls (1932), and Hubert de Givenchy and Audrey Hepburn had an enduring collaboration, most famously for Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961). Cardin and Moreau’s relationship in cinema (and life) is a testament to their shared artistic vision. -

democratization and pluralization

In 1959 Cardin showed his prêt-à-porter collection at the Printemps department store in Paris. The quality of commercially produced fashions had greatly improved, and Cardin envisioned his designs reaching a broader public. “It was my desire to make my creations accessible to a greater number of people by bringing [high] fashion to the street,” he has said. “This pushed me to invent ready-to-wear.” His motivation was both philosophical and practical: “For me, fashion should not be a privilege. And if you are going to be copied, might as well do it yourself.”

His ready-to-wear debut caused a scandal among his peers in the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, resulting in his temporary expulsion. He was reinstated by the Chambre Syndicale, however, and other haute couture designers would soon follow with ready-to-wear collections.

Fashion was becoming not only more democratic, but more pluralistic and individualized: the length of your skirt did not dictate whether you were in or out of fashion. As Cardin stated: “It would be insane to lengthen skirts just to follow an up-and-down cycle. It is ridiculous to change the silhouette every six months.” Instead, he created alternative visions of fashion that were photogenic in print and on film: sparkling evening wear and clothes for tomorrow’s world made from new fabrics, with reimagined silhouettes. These groundbreaking fashion presentations commanded attention and propelled Cardin’s reputation forward. -

First Success

The 1950s were a busy and productive time for Cardin. In 1957 he traveled to Japan for the first time, teaching three-dimensional cutting at the invitation of Bunka Fukuso Gakuin, a fashion college in Tokyo, where his students included future designers Hanae Mori and Kenzo Takada. The same year Pierre Cardin became a member of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, the association that designates which fashion houses are haute couture. The Chambre Syndicale's rigorous criteria for eligibility included presenting a minimum of fifty original designs for daytime and evening twice a year.

Although Cardin would continue designing couture, which is the focus of this exhibition, for decades to come, he also became interested in bringing his fashion designs to a wider public through prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear). -

Early Years in Paris

After Paris was liberated from the Nazis in August 1944, the twenty-two-year-old Cardin decided to leave Vichy for Paris. His first job in Paris was at Maison Paquin, where he was employed as a tailor beginning in November 1944. When Paquin was chosen to make the costumes for Jean Cocteau and René Clément’s film La belle et la bête (Beauty and the Beast), Cardin contributed to Jean Marais’s “Beast” ensembles and served as the actor's fit model.

After working at Maison Paquin, Cardin spent a short time at Elsa Schiaparelli’s atelier, before being hired as the first employee at Christian Dior’s new fashion house in November 1946. Cardin participated in the realization of numerous garments, including the legendary “Bar” suit—a pale pink jacket over a black skirt with a very defined waist that debuted February 12, 1947.

In 1950 Cardin left Dior and purchased Maison Pascaud, which specialized in stage and theater costumes, founding his own Pierre Cardin company. The house created costumes for numerous European masquerade balls, which were fashionable fund-raising events during the 1950s—including Count Carlos de Beistegui’s Le Bal Oriental, described as “the most beautiful ball of the century.” -

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion

The trailblazing designer, inventor, and businessman Pierre Cardin, whose name is one of the most recognized in the world, has continuously envisioned the future over a seven-decade career. Cardin not only reimagined the language of clothing with new silhouettes and materials, incorporating ideas of unisex and Space Age design that were radical at the time, but he also foresaw how fashion could be democratized—thereby altering its design trajectory and creating a new business model.

After spending twenty years as a master tailor, creating one-of-a-kind garments for an elite clientele, Cardin went on to blur the boundaries between haute couture and street fashion, launching his first prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear) collection in Paris in 1959. This astute design and business decision would become a much-copied model for competing fashion brands. In an even more audacious move, he also began in the 1960s to license his name and initials, emblazoning them on a wide range of products from clothing to interior design to cars and airplanes.

His success with licensing gave Cardin the creative freedom to explore new means of artistic expression, including industrial design (encompassing furniture, lighting, and vehicles), and to pursue other ventures. He acquired a Paris arts venue and reopened it as Espace Cardin in 1970 and subsequently purchased the famed French restaurant Maxim’s; his futuristic house in the South of France, the Palais Bulles; and a castle in Lacoste, where he now hosts a yearly music festival.

Cardin’s career is unparalleled in its breadth and success. In his groundbreaking and ever forward-looking career, he has changed the course of his profession.

-

June 18, 2019

Opening on the 50th anniversary of the Apollo moon landing, Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion focuses on the seven-decade career of pioneer of Space Age fashion and futuristic design

On view July 20, 2019–January 5, 2020

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion traces the legendary career of one of the fashion world’s most innovative designers, one whose futuristic designs and trailblazing efforts to democratize high fashion for the masses pushed the boundaries of the industry for more than seven decades. The retrospective exhibition features over 170 objects that date from the 1950s to the present, including haute couture and ready-to-wear garments, accessories, photographs, film, and other materials drawn primarily from the Pierre Cardin archive. Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion, curated by Matthew Yokobosky, Senior Curator of Fashion and Material Culture, Brooklyn Museum, will reveal how the designer’s bold, futuristic aesthetic had a pervasive influence not only on fashion, but on other forms of design that extended beyond clothing to furniture, industrial design, and more.

Pierre Cardin (French, b. 1922) is best known for his avant-garde Space Age designs and pioneering advances in ready-to-wear and unisex fashion. Cardin’s fascination with new technologies and the international fervor of the 1960s Space Race visibly influenced his couture apparel, which subsequently became emblematic of the era. His clothing designs, which featured geometric silhouettes and were often made from unconventional materials, were worn by international models and film stars from Brigitte Bardot and Lauren Bacall to Alain Delon, Jacqueline Kennedy, and Raquel Welch. Fueled by an appetite for experimentation and “breaking the mold,” he was one of the first European designers to show in Japan, China, and Vietnam and license his name, using it to brand an expansive line of products on a global scale.

“At the Brooklyn Museum, we’re dedicated to telling the stories of trailblazers from across the art world, and that’s exactly what Pierre Cardin is,” says Anne Pasternak, Shelby White and Leon Levy Director, Brooklyn Museum. “The storied French couturier has built a name for himself through his futuristic designs. His forward-thinking approaches to fashion and business have consistently established trends and practices in his field, making him one of the most influential designers of this generation.”

“Throughout his decades-long career, Pierre Cardin has proved to be a master tailor and designer, as well as an intuitive businessman,” says Matthew Yokobosky, Senior Curator of Fashion and Material Culture, Brooklyn Museum. “He truly is a twentieth-century renaissance man whose work has advanced fashion and design while continuously giving society a new and breathtaking vision of what the future might look like.”

The exhibition is organized chronologically, surveying pivotal moments throughout Cardin’s career. Included are recognizable pieces like the designer’s “target dress,” from his 1960s “Cosmocorps” collection; his investigations into unisex garment design and trendsetting menswear, such as the collarless suit jacket with slender “cylinder” pants; and clothing made for film and theater, such as the costumes worn by Mia Farrow in A Dandy in Aspic (1968) and by the iconic French actress Jeanne Moreau in Bay of Angels (La baie des anges) (1963). Film clips from his famous fashion shows at Espace Pierre Cardin (1970 onward), the Great Wall of China (1979), and Moscow’s Red Square (1991) are also featured.

While Cardin was one of the few couturiers who was able to draw, cut, sew, fit, and finish his own clothing, his designs went far beyond garments; he also designed furniture, lighting, and automobile interiors. Rarely seen “couture” furniture and home decor, as well as custom accessories including hats, jewelry, shoes, and sunglasses will be shown alongside archival photographs and excerpts from television, documentaries, and feature films. To put Cardin’s work in a larger historical context, scenes from early films that attempted to anticipate what the future would look like will also be on view. These include such films as A Trip to the Moon (1903), by French magician Georges Méliès, and Things to Come (1936), by visionary filmmaker William Cameron Menzies. The costume, set, and lighting designs for these films compliment Cardin’s futuristic fashions, providing a fuller picture of the fascination with outer space that dominated popular culture during the period.

Pierre Cardin

Trained in his teens as a tailor, Cardin lived in Vichy, France, during World War II and served in the Red Cross. Following the war, he moved to Paris, working at Maison Paquin and briefly at Elsa Schiaparelli before joining Christian Dior’s groundbreaking house in 1947. In 1950, Cardin founded his own fashion house, focusing first on costume design and then on haute couture. His ability to sculpt fabric with an architectural sensibility, which became his signature, was complimented by his love of geometry. For Cardin’s landmark 1964 “Cosmocorps” collection, he designed futuristic looks using vinyl, metallic fabrics, large zippers, and hats that resembled astronauts' helmets. Since then, he has continuously turned to futurism and new technologies for inspiration. Cardin introduced his own fabric in 1968, aptly named “Cardine,” which embraced a future of synthetic fabrics by molding a bonded, uncrushable Dynel fiber into three-dimensional patterns. In 1971, Cardin took an inspirational trip to NASA, where he became the only civilian in history to wear an original space suit worn by an Apollo 13 astronaut.

Cardin was the first couturier to launch a prêt-à-porter (ready-to-wear) collection, in 1958 at Parisian department store Printemps, and later to create a much-copied unisex clothing line. In the late 1960s, Cardin began to license his own name. The financial success of this unprecedented move allowed him to become one of the few designers to own his company outright. Through the years, the Pierre Cardin name appeared on over 850 licensed products, and, as a result, became one of the most recognized brands in the world. Entering new markets, Cardin—also a great diplomat—put on highly touted mega-fashion shows, featuring 300 “looks” on the Great Wall of China (1979), and in Moscow’s Red Square (1991), which was attended by over 200,000 people.

During the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, Cardin continued making clothes. He designed jackets and coats with extreme shoulder details that drew from designs as diverse as Chinese architecture and American football uniforms. Cardin also employed parabolic forms coupled with stretch jersey to “reshape” the body, which led to the invention of his signature biomorphic dresses. He has won numerous accolades not only for his fashion, including three Cartier Golden Thimble awards, but also for his humanitarian efforts. He is also the only fashion designer who has been admitted to the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris. In his lifetime Cardin has achieved an astonishing level of success, and at the age of 96 continues to walk to his office each morning and approach design with inventiveness and wonder.

This is a timed, ticketed exhibition. Information about ticket prices is forthcoming.

Pierre Cardin: Future Fashion is curated and designed by Matthew Yokobosky, Senior Curator of Fashion and Material Culture, Brooklyn Museum.

Leadership support for this exhibition is provided by Chargeurs Philanthropies.

Press Area of Website

View Original