Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_001_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_002_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_003_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_004_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_005_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_006_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_007_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_008_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_009_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_010_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_011_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_012_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_013_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_014_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_015_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_016_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_017_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_018_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_019_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_020_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_021_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_022_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_023_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_024_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_025_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_028_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_029_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_030_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_031_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_033_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_034_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_035_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_036_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_037_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_038_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_039_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_040_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_041_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_042_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_043_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_044_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_045_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_046_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_047_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_048_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_049_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_050_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_051_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_052_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_053_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_054_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_055_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_056_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_057_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_058_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_059_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_060_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_061_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_062_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_063_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_064_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_065_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_066_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_067_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_068_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_069_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_070_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_071_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_072_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_073_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_074_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_075_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_076_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_077_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_078_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_079_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_080_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_081_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_082_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_083_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_084_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_085_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_086_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_087_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_088_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_089_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_090_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_091_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_092_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_093_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_094_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_095_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_096_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_097_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_098_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_099_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_100_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_101_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_102_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_103_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_104_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_105_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_106_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_107_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_108_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_109_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_110_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_111_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_112_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_113_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_114_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_115_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_116_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_117_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_118_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_119_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_120_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_121_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_122_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic, March 13, 2020 through November 8, 2020 (Image: DIG_E_2020_Studio_54_Night_Magic_123_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2020)

Studio 54: Night Magic

-

Studio 54: Night Magic

For thirty-three months, from April 1977 to February 1980, the legendary nightclub Studio 54 emerged as a beacon of glamour and euphoric celebration amid difficult times. The disco craze of the 1970s offered respite as the United States was emerging from the Vietnam War, embroiled in the Watergate scandal, and rocked with ongoing liberation struggles for racial, gender, and sexual equality. Locally, New York City was on the brink of bankruptcy, and much of the city was in visible disrepair.

Low rents attracted artists, designers, and musicians with high ambitions who embraced Andy Warhol’s mantra that “success was a job in New York.” This influx of talent would galvanize New York City’s growing music scene. Armed with instruments, turntables, and vinyl records, musical innovators invented punk in Queens, hip-hop in the South Bronx, and disco throughout the boroughs, especially Manhattan. Studio 54, with its unexpected, ever-changing scenery and its dynamic soundscape, was at the pinnacle of these creative explorations. Its heady party atmosphere has become famous through both real and sensationalized accounts.

Studio 54: Night Magic tells the story of how Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell, two Brooklyn-born entrepreneurs, transformed a former opera house and television studio into one of the twentieth century’s most celebrated nightclubs. Studio 54 was a space of liberation, where people from diverse sexual, sociopolitical, and financial strata could find refuge and commonality, whether by taking a star turn on the dance floor or by voyeuristically observing the scene.

During its brief though historic years of operation, Studio 54 hosted celebrity-studded birthdays, anniversaries, New Year’s Eve parties, record launches, film premieres, and many spectacular disco nights. The images and stories of those fabled months continue to inspire the worlds of fashion, beauty, photography, music, and film today. -

New York City Nightclubs and The Paparazzi

New York City has a long history of storied nightclubs, where patrons could socialize, dance, and exchange conversation and ideas within a closed environment. Many clubs had a stern doorman who policed the entrance—as Studio 54 famously did—while others had more fluid door policies. Some of the most chronicled were the Cotton Club in Harlem, Café Society in the West Village, and the Stork Club, El Morocco, and the Peppermint Lounge in Midtown. Together with the fictional Tropicana nightclub from the television show I Love Lucy, these nightspots presented a sophisticated and free-spirited image of New York City in magazines, television, and cinema.

During the years that these nightclubs were in business—the 1920s through the 1960s—the United States also saw historic changes to discriminatory laws that prevented people from diverse backgrounds, sexual orientations, and gender identities from mingling publicly. The Cotton Club (1923–40) catered primarily to a white audience. Although it was located in Harlem and its staff and performers were largely local, Black patrons were typically seated in the back third of the venue. Café Society (1938–48) opened as the first truly integrated New York nightclub with no seating designations, and it achieved renown for the six-month residency of singer Billie Holiday, who concluded each performance with “Strange Fruit,” a chilling song about the lynching of African Americans.

Because of their celebrity clientele, nightclubs became popular with paparazzi and gossip columnists. Jerome Zerbe, the official photographer for El Morocco, was paid to take photographs for publication in newspapers. Publicity could be a double-edged sword, however. In October 1951, after dancer and singer Josephine Baker complained about receiving slow service at the Stork Club, protesters were photographed holding NAACP placards, and gossip columnist Walter Winchell, who regularly camped at the club, was called to task for not intervening on Baker’s behalf.

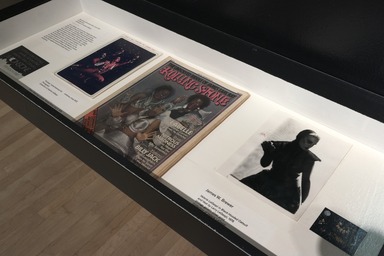

When Studio 54 opened in 1977, older outlets for celebrity photographs such as the long-standing National Enquirer thrived alongside newer ones, including People and Star (both first published in 1974) and Us (first published in 1977). These “supermarket tabloids” gained circulation through exclusives about celebrities and scandals that were often a collaboration between paparazzi, such as the highly successful Ron Galella, and magazine editors.

-

Recorded Music and The Clubs

Although the transition from live music to recorded music in nightclubs took many years, there was, from the start, a desire to create a seamless musical environment. In the late 1950s, Régine Zylberberg bought two record players and hired a DJ to alternate between records to create uninterrupted music at her Parisian nightclub, Chez Régine.

In New York during the 1960s, against the protest of musicians’ unions, some nightclubs began to play recorded music. The jukeboxes of earlier decades remained popular but necessitated mood-breaking silences between songs, while the practice of mixing records between two turntables allowed for continuous dancing. With the advent of record producer Tom Moulton’s extended 12-inch single in the early 1970s, and the ability to prerecord mixes on cassette and reel-to-reel players, DJs could create more “curated” styles and “authored” soundtracks. Many developments occurred in rapid succession, from the decision to include “instrumental versions” of songs on the B side to the incorporation of “breakdowns” (solo instrumentals within a song) to extend the length of a mix to more than ten minutes.

In the 1970s the art of DJing was primarily a manual activity—with a DJ alternating between two or three turntables, segueing between songs, to create a continuous soundscape for dancers. Small technological improvements, such as the ability to adjust turntable speed to bridge tempos across records, were seen as groundbreaking. The DJ’s intuition and creativity were crucial to keeping the beats flowing on the dance floor, and a few DJs, including Richie Kaczor and Roy Thode at Studio 54, developed celebrity status. -

Voyeuristic Architecture

In early 1977 nightclub owners Steve Rubell and Ian Schrager partnered with businessman Jack Dushey to acquire the property at 254 West Fifty-fourth Street that would become Studio 54. Over the next several months, they assembled an unlikely and inspired team of designers who worked outside the usual coterie of nightclub design professionals. Four of this team, working together as Experience Space—Ron Doud, interior designer; Scott Bromley, architect; Renny Reynolds, florist and event planner; and Brian Thomson, interior lighting designer—had previously created the Dianne B. storefront on Madison Avenue, the Backer & Co. beauty salon on the Upper East Side, Harriet Love’s vintage clothing store at 412 West Broadway, and the 1930s-inspired W.P.A. restaurant in SoHo.

Because they were transforming a theater into a nightclub animated by stagecraft, Schrager and Rubell also needed experts to design sets, lighting, and sound. Paul Marantz and Jules Fisher, who had designed lighting for Tony Award–winning productions, the nightclubs Electric Circus and Arthur, and rock concerts, were brought in to create a kinetic light experience. Marantz had also designed a women’s boutique on East Sixtieth Street with a lighting element that created horizontal waves of light flowing upward through the entire store.

Marantz and Fisher gave four presentations, from which Schrager and Rubell selected the artist duo known as Aerographics (Richie Williamson and Dean Janoff), whom they had met on a stage production for the New York rock band Kiss. Audio was engineered by Richard Long, who had been responsible for the sound system at various New York clubs, including Le Jardin. Together, these talents created a space, utilizing the theater’s existing infrastructure, that allowed patrons in the balcony, bars, and seating areas to watch the dynamic lighting, scenery, dancing, and fashions moving across the dance floor.

This exhilarating combination of high-end interior design, the original theater architecture, and changing, state-of-the-art sets, lighting, and sound created a sophisticated, often surprising environment that had never before been experienced in a New York nightclub. -

Iconic Scenery

Several times a night at Studio 54, a moon and a spoon would fly in separately from the left and right wings and meet center stage. The spoon would then twinkle and a line of lights would zip up the moon’s nose, referring to the use of cocaine. Like neon cocktail glasses during Prohibition and stenciled marijuana leaves during the 1960s, the Moon and Spoon symbolized Studio 54’s spirit of excitement and liberation. Cocaine, an illegal stimulant that was once an ingredient in Coca-Cola, was also known as “disco dust” (as well as “bump” and “snow”) during the 1970s.

In March 1977 Ian Schrager was introduced to Richie Williamson and Dean Janoff, known as Aerographics. Williamson and Janoff were noted for their spectacular airbrush work, and, in addition to the Moon and Spoon, they designed and executed the step pyramid, a dusk sky with silhouetted tree leaves surrounding the stage, and rockets that covered the chase poles (created for Elton John’s Rocket Records launch party).

For Studio’s renovation in August–September 1978, lighting designers Jules Fisher and Paul Marantz relocated the fanned neon backdrop from the Broadway production of Chicago to Studio 54, following the original show’s two-year run. Designed by Tony Award–winning set and costume designer Tony Walton, the neon fan would become another visual icon of the nightclub. From 1977 to 1980, Walton, Aerographics, and Mark Ravitz would propose new imagery for both the permanent dance space and one-night-only events. Some unrealized examples on display nearby include elaborate neon dancers, a deco-style proscenium curtain with traveling scenery, and otherworldly landscapes. -

Who's Who: Studio 54 and Interview

By the time that Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine held its tenth-anniversary party at Studio 54 in June 1979, the nightclub was already into its third year of business. A curtain drop was composed for the party featuring all the covers from the magazine’s history. On display here are some of the original working photographs and paintings for those Richard Bernstein Interview covers, featuring luminaries who were part of the Studio social scene. The who’s who included models Iman and Paul van Ravenstein, actors Mariel Hemingway, Liza Minnelli, Tatum O’Neal, and Elizabeth Taylor, singers Cher, Mick Jagger, Grace Jones, Olivia Newton-John, and Diana Ross, and Interview contributor Truman Capote.

Interview magazine covers were the result of an extensive collaborative process. Once selected by Andy Warhol and editor Bob Colacello, the subject would be photographed, and interviewed for the inside article, often by another celebrity. For the cover portrait, Warhol and Colacello would bring together a photographer such as Francesco Scavullo, in collaboration with makeup artist Way Bandy and hair designer Harry King. For the tenth anniversary of Interview, Debbie Harry, lead singer of Blondie, was chosen as the subject, following the group’s Number 1 single “Heart of Glass.” For this cover, photographer Barry McKinley, makeup artist and Studio regular Sandy Linter, and Harry King produced the photograph, on which Richard Bernstein based the final artwork. -

Disco Fashion

Although Studio 54 opened the same year that Saturday Night Fever was released in movie theaters, fashion at the nightclub differed from what was seen in the film. The main character Tony Manero’s store-bought three-piece white suit with black shirt was a quintessential 1970s look, but by the time the film opened, it was decidedly out of fashion in New York City. Instead, many of the dancers and celebrities at Studio wore sultry designs by Stephen Burrows, Halston, Norma Kamali, and Calvin Klein, or imaginatively developed their own personal styles.

Choosing an outfit to wear to Studio 54 often depended on your motivation for going. For some, it was about looking glamorous or unusual to get past the velvet rope. For others, it was a question of whether they would actually be dancing, or just cruising or gazing voyeuristically from the sidelines or balcony.

Burrows, Halston, Kamali, Klein, and Giorgio di Sant’Angelo were fashion superstars in the 1970s, creating many of the silhouettes worn to Studio 54. Halston often pronounced in interviews, “You are as good as the people you dress,” and his clients included Studio 54 habitués Doris Duke, Elizabeth Taylor, Liza Minnelli, and Barbara Walters. Kamali, who designed the high-cut-leg red bathing suit Farrah Fawcett wore in her iconic poster, advanced the idea (along with Sant’Angelo) of the swimsuit with wrap skirt as evening wear—a popular look at Studio. Calvin Klein began the Studio era with clingy, 1930s-inspired slip dresses, and ended the 1970s with lamé dance ensembles and highly coveted designer blue jeans, competing with Gloria Vanderbilt and Kamali’s Studio 54 Jeans for the emerging market.

Of equal note, some one-of-a-kind outfits at Studio were created by designers who imagined fashion more as artistic expression, evoking period and Space Age fantasies. These designs included Philip Haight and Ronald Kolodzie’s elaborate ensembles for performance artist Richard Gallo, Larry LeGaspi’s silver and lamé glam rock designs, Zandra Rhodes’s ethereal, silkscreened sheaths, and Yves Saint Laurent’s Chinese fantasies. These creations added intrigue and mystery to the kinetic, dreamlike spectacle at Studio 54. -

Lighting in a Bottle

“I think Studio 54 brought glamour back to New York that we haven’t seen since the sixties—it made New York get dressed up again.”

—Liza Minnelli, at Studio 54’s first anniversary in 1978

“[Studio 54] is everything the way it ought to be. It’s very democratic. It’s all kinds of colors. All kinds of sizes. Boys and boys together. Girls and girls together. Girls and boys together. Poor people. Rich people. Taxi drivers. Anything you want. It’s all mixed up together and that’s what I like about it.”

—Truman Capote, on The David Susskind Show, February 1979

Studio 54 has been called lightning in a bottle, and truly it was. For thirty-three charged-up months, the nightclub infused a depressed New York City with vibrancy, glamour, and a new attitude. Today, artists, dancers, designers, musicians, photographers, filmmakers, and fledgling nightclub entrepreneurs all continue to find creative inspiration in the night magic of Studio 54.

"You remember your first time at Studio 54. I remember distinctly. I had been away from New York. I was working in London making a film with Twiggy called The Boyfriend and I stayed, working in the West End. Then I came back to the city. First night back, they said you’ve got to come to Studio 54. Now I lived at 145 West 55th, on the 13th floor. 13A was my apartment. Directly across from me—13B—who lived there? Steve. So, I had no trouble getting in. He was my neighbor. And so, while I was away in London, there was this thing called the Hustle that got invented that was like a line dance. Now I’d never seen that, never heard about it.

I come here, we walk into Studio 54 and, of course, the lights are the thing. Jules Fisher. Those lights . . . it’s like being onstage. Oh, I understand—this is what we feel when we’re on stage center. The follow-spots and all the lights coming at you. He’s made it possible for everybody to feel this. So that was that wonderful thing where everybody felt like a star when you walked in, because the lights hit you. And you know, that’s a big deal.

But here’s the drip. Everybody on the dance floor was doing the same dance. And I went, “Well, do they have a choreographer that teaches everybody?” I was bowled over. I couldn’t believe it for a moment. I’m not sure how straight I was at the time, but I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I thought it was an illusion."

—Tommy Tune, choreographer and director, on the Marc and Myra Show, SiriusXM

"I remember getting past the doorman and there was a carpeted hall. . . .It looked almost like a runway, and it was mirrored. The coatroom was to the right. I just remember hearing the music and I threw my coat! There was a rush to get to the dance floor, just a rush."

—Sandy Linter, makeup artist and Studio 54 regular, in the documentary Studio 54 (Matt Tyrnauer, 2018)

-

New York City in the 1970s

When Studio 54 opened on April 26, 1977, it was a jewel amid broken bottles.

The 1970s were years of great social, political, and economic upheaval in the United States. Nationwide protests for the rights of the LGBTQ+ community, African Americans, women, and other marginalized groups were unrelenting. The year 1973 saw an oil embargo, gas rationing, and long lines at gas stations. In 1974, under threat of impeachment following the Watergate inquiry, Richard M. Nixon became the first American president to resign, undermining public trust in government. And in 1975 America finally exited decades-long conflicts in Southeast Asia, while New York City, plagued by a stagnant economy, barely escaped bankruptcy after being initially refused federal assistance by President Gerald Ford (memorialized in the Daily News headline “Ford to City: Drop Dead”).

Although the city had celebrated successes, such as the completion of the World Trade Center in 1973, many neighborhoods were in disrepair and awash in graffiti. In the summer of 1976, serial killer Son of Sam began a yearlong spree that terrorized New York City. Crime was rampant. “The seventies was a lot of robbery, shootings, muggings, crack addicts. People stole radios; there were signs in cars that said, ‘no radio,’” recalls Judy Licht, then a reporter for Channel 5. “Crime was cheap and titillating. ‘If it bleeds, it leads’ was an operating principle.”

Not long after Studio 54 opened, New York experienced a crippling two-day blackout. Ironically, on July 15, 1977, the day after the blackout, the New York State Department of Commerce, in collaboration with graphic designer Milton Glaser, launched the “I ♥ NY” campaign. New York was beginning to rebrand, and Studio 54 brought the spotlight back to Gotham’s glamour and creative energy. -

Kinetic Lighting

Even before it became Studio 54, the building at 254 West Fifty-fourth Street had always been used as a performance space. Originally built as the Gallo Opera House in 1927, it subsequently housed a succession of theaters in the 1930s and became Columbia Broadcasting Company’s Studio 52—a television studio for both live and prerecorded programs—from 1943 until it was acquired by Rubell, Schrager, and Dushey three decades later. Because the theater building had a fly space (an empty space above the stage where flying scenery could be attached and housed) that was eighty-four feet high, as well as a proper proscenium arch to hide the behind-the-scenes apparatus, changes of scenery could be frequent, seamless, and magical.

While the interior spaces were being renovated in spring 1977, the stage was dismantled to make room for a parquet dance floor, but the proscenium, extensive air-conditioning, and theatrical rigging were retained. Feeling that light-up dance floors and mirror balls were passé, Schrager asked Paul Marantz and Jules Fisher to design kinetic lighting.

Approaching the project, Marantz and Fisher decided to “make it bright,” in contrast to the typically dark discos of the time. Twelve “chase poles” festooned with red and yellow bulbs were wired together in groups and programmed to fool the eye into seeing moving light. The poles themselves could move up into the fly space and down onto the dance floor, while the red and yellow lights could flash in faster or slower progressions. The lowering of the poles right into the moving throng below and the timing of the lights were done manually, accentuating the music. Attached to the bottom of each pole was a white rotating police car beacon, an idea hatched while watching a police car race across an Arizona desert at high speed. Later, lighting designer Bran Ferren reimagined Studio 54 as a “pure space” and had the black lighting fixtures painted white.

Marantz and Fisher would continue to adjust, propose, and implement new designs over the next three years. These included a sixty-foot-wide rotating mirror to reflect light across the dance floor—which was suggested by Schrager after seeing Chip Monck’s lighting design for a Rolling Stones concert—and, in 1979, purple tarmac lights on a bridge that moved above the dancers. -

Thirty-Three Months of Fame and Celebration

When a special event was scheduled at “Studio,” as regulars called it, paparazzi and newspaper photographers would be alerted to document the event. Birthdays, anniversaries, movie premieres, record launches, book parties, benefits, and special occasions would include staged and timed photo ops that allowed the photographer to get a quick celebrity shot and move on to the next of several events in town the same evening. With luck, the image would be published, the photographer would have a payday, and Studio 54 and the celebrity would get publicity—a symbiotic relationship.

On April 27, 1977, a photo of Cher at Studio’s opening the previous night made the front page of the New York Post. On May 4, 1977, the day after Bianca Jagger’s birthday party at Studio, an image appeared on the front page of the Daily News of her feeding cake to Mick Jagger. An inside spread titled “Wee Hours, High Times” featured one of many now-iconic images of her astride a white horse at the same event that made international news.

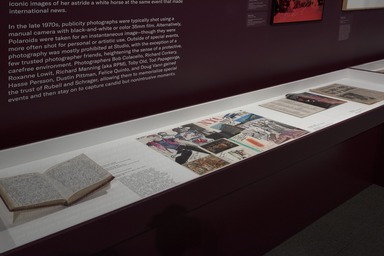

In the late 1970s, publicity photographs were typically shot using a manual camera with black-and-white or color 35mm film. Alternatively, Polaroids were taken for an instantaneous image—though they were more often shot for personal or artistic use. Outside of special events, photography was mostly prohibited at Studio, with the exception of a few trusted photographer friends, heightening the sense of a protective, carefree environment. Photographers Bob Colacello, Richard Corkery, Roxanne Lowit, Richard Manning (aka RPM), Toby Old, Tod Papageorge, Hasse Persson, Dustin Pittman, Felice Quinto, and Doug Vann gained the trust of Rubell and Schrager, allowing them to memorialize special events and then stay on to capture candid but nonintrusive moments. -

DJs

The first DJ at Studio 54 was Richie Kaczor, and the first song he performed was C.J. & Company’s “Devil’s Gun,” with its insistent rhythm and cautionary lyrics: “We’ve gotta make a stand against the devil’s gun.” Kaczor, whom Rubell first heard at the nightclub Hollywood, is famously credited with the breakout success of Gloria Gaynor’s “I Will Survive.” Originally released in October 1978 as a B side to “Substitute,” “I Will Survive” was frequently spun at Studio on any given night, and it was the first track on Kaczor’s Steppin’ to Our Disco, a promotional album of Polydor’s best disco hits. “I Will Survive” would win a Grammy Award for Best Disco Recording in 1980 and become a modern anthem for acceptance and rights for all.

Most songs did not have such a direct or meaningful message, and instead flirted with the sensual nature of disco and dancing. From Joe Simon’s “Love Vibration” to Musique’s scandalous “In the Bush,” the lyrics, smooth orchestrations, driving beats, and extended mixes provided a soundscape that, in combination with lighting and set changes, allowed dancers and viewers to lose their sense of time and place. Some of the environmental changes at Studio included “playing with the weather,” when the air-conditioning would be turned off briefly to warm up the crowd before releasing a blast of cold. Other times there would be a three-minute scripted event, such as a sparkler parade. But, former manager Michael Overington recalls, it was always important to “play to the crowd, and not lose the room.” And so the DJ provided music that acted as a soundtrack for the sets, lighting, and activities, much like the soundtrack in cinema, bridging myriad scenes and settings. -

Friends We Lost

Following the many years of struggle for LGBTQ+ liberation and the dramatic events of the Stonewall Rebellion of 1969, when patrons took to the streets in protest against a police raid at the Stonewall Inn bar in Greenwich Village, the 1970s seemed like an Eden. This decade saw the emergence of nightclubs such as the Loft, the Tenth Floor, Flamingo, the Gallery, Infinity, and Le Jardin that were primarily members-only and catered to gay audiences. In the later 1970s, openly gay musicians such as Sylvester and the Village People experienced mainstream success, with “You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)” and “Y.M.C.A.” topping the dance charts. Rubell and Schrager openly embraced the LGBTQ+ community, believing that a “mixed” environment was more enjoyable for everyone.

The seventies’ celebratory moment was soon followed by a tragic jolt. On July 3, 1981, a report appeared in the New York Times titled “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” The article described an aggressive and fatal form of cancer—which was later given the acronym AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Many people who had felt liberated were suddenly put in the spotlight for contracting an as-yet unknown, deadly virus. AIDS took a heavy toll on the Studio 54 circle. In the 1980s and into the 1990s, many visited hospitals and funeral homes more often than nightclubs as they said goodbye to friends, who included Studio regulars Way Bandy, Kevin Boyce, Gia Carangi, Tina Chow, Roy Cohn, Ron Doud, Perry Ellis, Halston, Victor Hugo, Paul Jabara, Richie Kaczor, Larry LeGaspi, Richard Long, Antonio Lopez, Rudolph Nureyev, Juan Ramos, Sterling St. Jacques, and so many more.

Steve Rubell himself died on July 25, 1989, after learning years before that he had contracted HIV (human immunodeficiency virus, which causes AIDS). Because of the stigma attached to the disease, his obituary gave the cause of death as hepatitis and septic shock.

While government support for HIV research was initially scarce, Studio 54 celebrities were among those in the arts community who responded to the crisis. Elizabeth Taylor cofounded the American Foundation for AIDS Research in 1985 and started her own Elizabeth Taylor AIDS Foundation in 1991. The Elton John AIDS Foundation was established in 1992. -

Studio 54—A Style, and Attitude

Studio 54 was influential during its heyday, inspiring especially Fabrice Emaer’s theater-turned-nightclub Le Palace in Paris, which opened in 1978 and continues to operate today. But the concept of the highly curated dance floor and a spectacular, cocooned environment where fashionable, creative, and sexually liberated people of diverse races and gender identities could connect has endured and resonated for more than four decades through images and films taken at Studio 54.

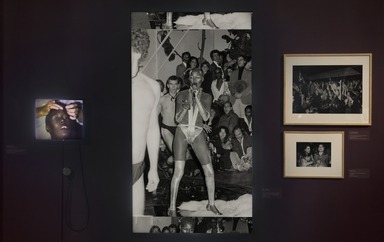

Through the 2010s allusions to disco’s glitter and flash, especially in fashion, were often described as “inspired by Studio 54.” Bold images synonymous with Studio 54—whether visions of Bianca Jagger in a red Halston gown astride a white horse, of Richard Gallo standing in the middle of the dance floor with one Haight-Kolodzie sequined glove held high sparkling under the lights, or of Grace Jones swathed in gold lamé Kamali singing “I Need a Man”—frequently appear on fashion designers’ mood boards and engender new collections. Kenzo’s Spring 2017 collection by Humberto Leon and Carol Lim was inspired by Kenzo’s 1977 fashion show at Studio 54 and period drawings by Antonio Lopez, and Elie Saab’s Spring 2017 “Standing on Stardust” collection was based on Studio’s famous diamond-dusted 1978–79 New Year’s Eve Party. Anthony Vaccarello’s Spring 2019 Men’s Collection for Yves Saint Laurent represented the idea of the icons of New York in the seventies” and was presented with an ultramodernized version of the Opium launch party forty years earlier. For the finale, presented across the Hudson River in New Jersey with the New York City skyline in the background, the models were painted silver, in reference to patrons who arrived at Studio 54 in full silver body makeup.

Recent collections by disco-era pioneer Norma Kamali reference her own Studio 54 era. Having designed the “slinky dress,” the parachute skirts, dresses, and coats, and the iconic sleeping bag coat—all looks seen at Studio—Kamali uses her archive as inspiration to reinterpret and re-edition earlier designs, now emphasizing that the pieces can be worn by people of all gender identities. Today, she states: “Imagine that you walked into a clothing store, and there were just clothes and everyone selected from the same racks.”

Rick Owens has long been inspired by the trailblazing American designer Larry LeGaspi. In his Fall/Winter 2019 “Larry” collection, he references LeGaspi’s trapunto quilting technique, lamé and geometric futuristic fashions, and iconic glam rock designs for Kiss, Labelle, and Parliament Funkadelic, injecting disco-era flourishes and silhouettes into his own cutting-edge ready-to-wear.

-

September 10, 2019

Highlighting the revolutionary creativity, expressive freedom, and sexual liberation celebrated at the world-renowned nightclub, the exhibition will present nearly 650 objects ranging from fashion, photography, drawings, and film to stage sets and music

Following the Vietnam War, and amid the nationwide Civil Rights Movement and fights for LGBTQ+ and women’s rights, a nearly bankrupted New York City hungered for social and creative transformation as well as a sense of joyous celebration after years of protest and upheaval. Low rents attracted a diverse group of artists, fashion designers, writers, and musicians to the city, fostering cultural change and the invention of new art forms, including musical genres such as punk, hip-hop, and disco. In a rare societal shift, people from different sexual, sociopolitical, and financial strata intermingled freely in the after-hours nightclubs of New York City. No place exemplified this more than Studio 54.

Though it was open for only three years—from April 26, 1977, to February 2, 1980—Studio 54 was arguably the most iconic nightclub to emerge in the twentieth century. Set in a former opera house in Midtown Manhattan, with the stage innovatively re-envisioned as a dance floor, Studio 54 became a space of sexual, gender, and creative liberation, where every patron could feel like a star. Studio 54: Night Magic is the first exhibition to trace the groundbreaking aesthetics and social politics of the historic nightclub, and its lasting influence on nightclub design, cinema, and fashion. The exhibition is curated and designed by Matthew Yokobosky, Senior Curator of Fashion and Material Culture, Brooklyn Museum.

“Studio 54 has come to represent the visual height of disco-era America: glamorous people in glamorous fashions, surrounded by gleaming lights and glitter, dancing ‘The Hustle’ in an opera house,” says Yokobosky. “At a time of economic crisis, Studio 54 helped New York City to rebrand its image, and set the new gold standard for a dynamic night out. Today the nightclub continues to be a model for social revolution, gender fluidity, and sexual freedom.”

Anne Pasternak, the Brooklyn Museum’s Shelby White and Leon Levy Director, adds, “At this current moment in history, when struggles for liberation often collide with restrictive social norms, we are excited to present Studio 54: Night Magic. The exhibition encourages visitors to reflect on a significant era in our shared history and challenges us to consider the future and the many ways we can create a freer and more just world.”

Studio 54 was founded in 1977 by Brooklyn-born entrepreneurs Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell, who met while students at Syracuse University. The pair had dreams of opening a disco club in the center of New York City, where roller-skating rinks, Black and Latinx dance culture, and gay underground nightclubs were gaining popularity. From the moment Studio 54 opened, its cutting-edge décor and state-of-the-art sound system and lights set it apart from other clubs at the time, attracting artists, fashion designers, musicians, and celebrities whose visits were vividly chronicled by notable photographers. Regulars included Andy Warhol, Bianca Jagger, Cher, Elizabeth Taylor, Farrah Fawcett, Liza Minnelli, Michael Jackson, Mick Jagger, Pat Cleveland, and Truman Capote. Singers Grace Jones, Diana Ross, and Donna Summer all performed at Studio 54. Fashion designers Kenny Bonavitacola, Stephen Burrows, Diane von Furstenberg, Halston, Norma Kamali, KENZO, Calvin Klein, Larry LeGaspi, Issey Miyake, Claude Montana, Robert Lee Morris, Zandra Rhodes, Yves Saint Laurent, Fernando Sanchez, and Giorgio di Sant’Angelo were frequently present, as were beauty experts Harry King and Sandy Linter.

In addition to presenting the photography and media that brought Studio 54 to global fame, the exhibition conveys the excitement of Manhattan’s storied disco club with nearly 650 objects ranging from fashion design, drawings, paintings, film, and music to décor and extensive archives. The design of the exhibition itself is inspired by Studio 54’s original lighting and features innovative sets and audio elements that highlight the popular music and film of the era—including chart-topping songs like “Le Freak,” famously written after the band Chic was denied entry to the nightclub’s 1977 New Year’s Eve party, and “I Will Survive,” Gloria Gaynor’s B side that became an anthem after it was championed by Studio 54’s DJ Richie Kaczor.

Studio 54: Night Magic is organized chronologically, starting with a look back at popular New York nightclubs from the 1920s to the 1960s, including the Cotton Club, the Tropicana, El Morocco, and the Peppermint Lounge, which became dynamic venues that brought together groups of people of diverse backgrounds, sexual expressions, and sociopolitical beliefs. Through photography and video, the exhibition introduces New York City in the 1970s, and showcases the unique new forms of artistic expression that proliferated during this period, with particular emphasis on disco music.

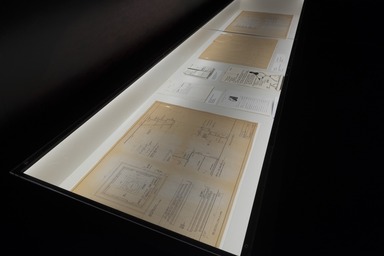

The exhibition explores the development and creation of Studio 54, including original blueprints, sketches, and models not seen since the 1970s, which trace the renovation of the former Gallo Opera House and CBS soundstage on West 54th Street that would become Studio 54. Featured designers and artists include Richard Bernstein and Antonio Lopez; and Aerographics (Richie Williamson and Dean Janoff), who designed the huge “Moon and Spoon” sculptural decoration that hung inside the club, Academy Award–winning set designer Tony Walton, Tony Award–winning lighting designers Jules Fisher and Paul Marantz; Ron Ferri; and architect Scott Bromley. Also featured are artists Victor Hugo and Richard Gallo, who spanned the performance and fashion worlds.

A section titled The Studio 54 Experience showcases the nightclub’s most extravagant and legendary theme parties, such as the grand opening headlined by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater; the 1978 New Year’s Eve party featuring Grace Jones’s unforgettable 3 am performance; the first anniversary party visually conceived by Issey Miyake; and events celebrating the release of the films Grease (1978) and Thank God It’s Friday (1978), which spawned Donna Summer’s hit song “Last Dance,” written by Brooklyn-born Paul Jabara. A vast collection of photographs chronicling the nightclub’s entire history are featured, including iconic works by photographers Ron Galella, Rose Hartman, Roxanne Lowit, Richard Manning, Meryl Meisler, Miestorm, Anton Perich, Hasse Persson, Dustin Pittman, Adam Scull, Allan Tannenbaum, and Doug Vann, as well as more infrequent photographers, including Bob Colacello, George DuBose, Larry Fink, Christopher Makos, Guy Marineau, Toby Old, Tod Papageorge, Robin Rice, and Charles Tracy.

Also showcased are more than fifty costume sketches by Antonio Lopez for the opening night performance by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which have not been on public view since 1977, and unrealized set proposals by Mark Ravitz, Tony Walton, and Richie Williamson. A selection of rarely seen items from Studio 54 staff members Carmen D’Alessio, Marc Benecke, L. J. Kirby, and Myra Scheer will be highlighted, in addition to Elizabeth Taylor’s fabled sapphire necklace from the BVLGARI Heritage Collection. The 62-carat Burmese sapphire necklace was given to the actress by her husband Richard Burton on her fortieth birthday and worn at Studio 54 on May 21, 1979, on the occasion of the Martha Graham Awards, honoring Halston.

As the popularity of the club escalated, the business practices of the owners, Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell, came under scrutiny, resulting in brief prison sentences for both and the liquidation of Studio 54 in February 1980 (Schrager received a full pardon from President Obama in January 2017). The exhibition explores Schrager and Rubell’s years following their release, when, dubbed “Comeback Kids” by New York magazine, the pair produced the highly popular New York nightclub Palladium and later developed the concept of “boutique” hotels, beginning with Morgans and the Paramount. After the death of Rubell, Schrager went on to open hotels such as the Delano, Mondrian, Hudson, and Gramercy Park Hotel, and, most recently, PUBLIC and EDITION.

In the 1980s, Rubell learned he had contracted AIDS, and he passed away in 1989. A section of the exhibition is devoted to the artists, friends, and patrons of Studio 54 who died from AIDS and other causes.

In its short lifespan, Studio 54 became a social phenomenon and made a profound impact on contemporary culture. The exhibition concludes with a presentation of Studio 54’s influence on nightclub design and its lasting legacy within the fashion and beauty industries. Contemporary fashion designs from CARR, KENZO, Rick Owens, and others demonstrate how the dazzling disco aesthetics of Studio 54 continue to inspire creative people today.

Lead sponsorship for this exhibition is provided by Spotify. Major support provided by Perrier.

“The cultural impact of Studio 54 transcends generations and has undeniably shaped the way people consume and listen to music,” says Alex Bodman, Vice President, Global Executive Creative Director, Spotify. “We are honored to once again partner with the Brooklyn Museum on an exhibition that brings to life such a rich history across music and fashion.”

Studio 54: Night Magic

View Original