Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_01_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_02_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_03_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_04_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_05_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_06_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_07_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_08_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_09_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_10_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_11_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_12_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_13_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_14_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_15_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_16_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_17_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_18_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_19_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_20_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_21_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_22_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_23_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_24_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_25_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_26_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_27_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_28_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_29_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_30_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_31_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_32_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_33_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_34_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_35_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_36_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_37_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_38_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_39_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_40_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_41_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_42_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_43_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_44_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_45_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_46_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_47_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_48_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_49_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_50_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_51_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_52_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_53_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_54_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_55_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_56_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_57_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_58_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_59_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_60_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_61_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_62_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_63_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_64_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_65_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_66_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_67_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_68_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_69_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_70_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_71_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_72_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_73_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_74_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_75_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_76_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_77_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_78_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_79_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_80_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_81_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_82_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_83_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_84_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_85_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_86_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_87_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_88_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_89_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_90_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_91_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_92_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_93_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And, March 5, 2021 through July 18, 2021 (Image: DIG_E_2021_Lorraine_O%27Grady_Both_And_94_PS11.jpg Photo: Jonathan Dorado photograph, 2021)

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And

-

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And

Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And is the first retrospective of an artist who has been a critical voice in performance, conceptual, and feminist art for more than four decades. Lorraine O’Grady became an artist at age forty-five, after successful careers in the U.S. Departments of State and Labor, professional translating, rock criticism, and teaching French literature and art. She jokes that because she came to her artistic career late in life, she “only had time for masterpieces.”

O’Grady’s work revolves around a consistent set of themes: Black female subjectivity and Black feminism; hybridity and diaspora; the unspoken aftermath of slavery in the Western Hemisphere; the contradictions and complications of her upbringing in Boston as the daughter of Jamaican immigrants; and the impossibility of separating the personal from the political, or the self from history. The artist’s practice is driven by a desire to replace Western “either/or” thinking—which O’Grady sees as the basis of the inequalities that structure our world—with the concept of “both/and.” By putting seeming contradictions into play and refusing the possibility of resolution, O’Grady seeks to undermine the power and hierarchy implied by oppositions like Black and white, self and other, West and non-West, and past and present.

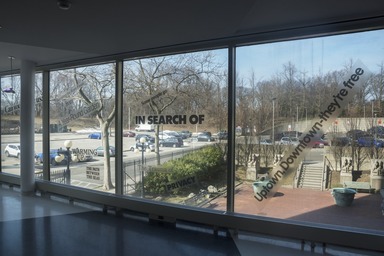

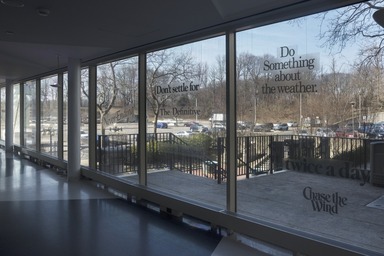

Comprising almost all of O’Grady’s concise oeuvre, Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And is presented in multiple galleries throughout the Museum, including the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art and elevator lobby on the fourth floor; the Luce Center for American Art on the fifth floor; the Beaux-Arts Court and Egyptian Galleries on the third floor; and the Café on the first floor. These interventions, and the back-and-forth conversations they spark, acknowledge the ways the artist challenges canonical art history in the Brooklyn Museum and beyond. -

Diptychs and Collapsed Diptychs

Lorraine O’Grady visually and conceptually favors the format of the diptych (two images placed side by side) for its capacity to foster complexity and contradiction. The artist has written, “If you had told me when I started forty years ago that the form of my work would prove to be more important than the content, I would probably have laughed. But the diptych, whether expressed or implied, has always been my primary form. . . When you put two things that are related yet dissimilar in a position of equality on the wall, they set up a ceaseless and unresolvable conversation. The diptych, appearance to the contrary, is anti-dualistic. That’s why it’s been my weapon of choice to oppose the West’s either/or binary, which is always exclusive and hierarchical.”

A close look at O’Grady’s work reveals the diptych—and its implication of both/and thinking—everywhere. It is visible, for instance, in the expressions of anger and joy of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, and in the equal number of Black and white artists in The Black and White Show. In the works on display in this gallery, the form is more materially present. Body Is the Ground of My Experience and Cutting Out CONYT use the diptych to grapple with the ways in which our most subjective, intimate experiences are shaped and determined by historical and contemporary forces, including the history of slavery and forced migration, the colonization of the Americas, and the language of media and commerce. Occasionally, the idea of the diptych emerges in a single image that contains an inner contradiction: O’Grady calls these “collapsed” or “internal” diptychs. The Fir-Palm, one of the panels that make up Body Is the Ground of My Experience, is an example of a collapsed diptych. -

Body is the Ground of My Expereince

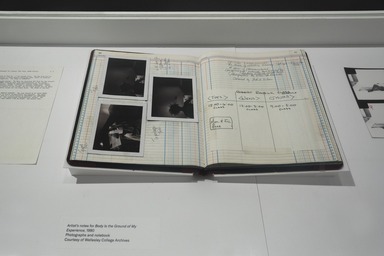

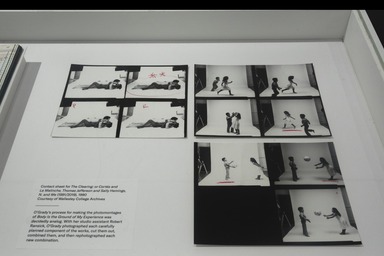

For the photomontages that make up Body Is the Ground of My Experience, Lorraine O’Grady painstakingly photographed individual components in the studio and then cut them out and combined them, drawing on Dada and Surrealist techniques. Rather than seeking out randomness, as those European artists of the 1920s and 1930s had done, O’Grady hoped that by twisting rational sources, the voice of the “other” might enter—to speak of the immigrant experience, the power relations that underlay interracial encounters, and the fantasies of creation and destruction often projected onto the image of the Black woman. In the series, O’Grady displays her virtuosity with the diptych, a form that allows her to set up a never-ending back-and-forth between seemingly contradictory ideas. In some cases, the form is, as the artist terms it, “collapsed,” so that the contradiction in image and concept is present in a single panel.

The wall labels for the individual works in this series are quotations from O’Grady herself, who wrote them for their first exhibition in 1991. In the face of the lack of institutional support that many Black women artists have encountered in a predominantly white art world, O’Grady has acted as creator, curator, and interpreter of her own work for much of her career. -

Origin Stories

This gallery contains two of Lorraine O’Grady’s earliest forays into visual art and performance. Though they take very different forms, both groups of works signal the related themes, ideas, and aesthetic strategies that would occupy the artist for the next forty years and that continue to do so today.

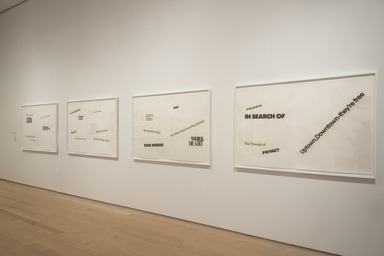

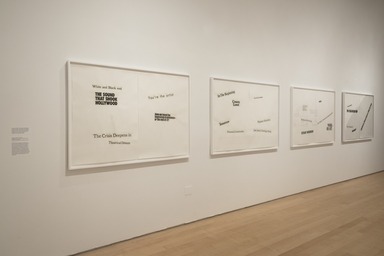

For Cutting Out the New York Times, a series of collage-poems made in 1977, O’Grady cut text out of the Sunday newspaper to create concrete poetry—poems in which the material heft of the words (in this case, ink on newsprint) and their arrangement in space are as important as the ephemeral quality of language itself. Her goal was to take language that was available in the public realm and see if she could craft it into verses that exposed her most intimate self. Rivers, First Draft, or The Woman in Red was presented in a secluded corner of Central Park in 1982. O’Grady described the performance as a “collage in space” that drew on aspects of her own biography to comment on her entry into the art world, including the family dynamics of her Boston-by-way-of-Jamaica family, her awakening feminism, and her creative coming-of-age.

Both of these pieces engage with legacies of European Futurist, Dada, and Surrealist art from the 1920s and 1930s, movements O’Grady taught in classes at the School of Visual Arts beginning in 1974. Cutting Out the New York Times and Rivers, First Draft share a desire to speak simultaneously to questions of subjective individual experience and the larger forces that shape the self—whether political, historical, gendered, or racial. -

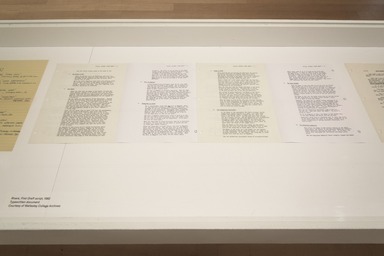

Rivers, First Draft, or The Woman in Red

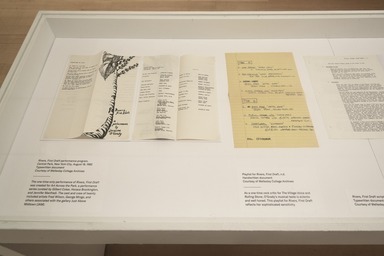

O’Grady conceived of Rivers, First Draft, or The Woman in Red as a “collage in space.” Sited simultaneously on two sides of a stream and a nearby hill in the Loch (a northern part of Central Park), it was performed on August 18, 1982, in front of a small audience of friends and the occasional passerby.

With three narratives competing for viewers’ attention, Rivers, First Draft was an animated and dreamlike exploration of the artist’s biography, including her upbringing in Boston’s Caribbean diaspora, her emergent feminism, her creative coming-of-age, and her traumatic encounters with art world politics. A key framing device for the performance was the metaphor of the Crossroads, as it is understood in African diasporic religions such as Haitian Vodun.

The overlapping and intersecting storylines speak of the artist’s path from childhood to the trials she encountered as a young artist making her way in the world and, finally, to her artistic independence. The main characters include the Little Girl with Pink Sash (O’Grady’s childhood self), the Teenager in Magenta (an adolescent O’Grady), the Woman in Red (O’Grady as an adult), and the Woman in White. Representing the artist’s mother and her Jamaican heritage, the Woman in White is a beautiful, if aloof, figure whose singular task is to grate coconut. The Nantucket Memorial, a figure in a makeshift boat and foul-weather gear, represents New England, where O’Grady was raised. The narrative follows the Woman in Red as she navigates the New York art world of the 1970s, where her gender and her Blackness exclude her from both Black and white artists’ circles. Art Snobs, Black Male Artists, and the Debauchees act as choirs framing her fraught social encounters, which include a symbolic assault. The artist’s moment of self-actualization occurs when she spray paints a white stove red, signaling her political transformation via feminism and her release from her mother’s oppressive cultural dictates. The narrative culminates as O’Grady’s childhood, adolescent, and adult selves unite to walk down the stream together.

O’Grady has called Rivers, First Draft her most overtly feminist work, and regards the moment when her three selves join to begin their journey of independence as the birth of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, the artist’s iconic alter ego. -

The Mlle Bourgeoise Noire Project

The three projects in this room feature Lorraine O’Grady’s most famous performance persona, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (Miss Black Middle Class). The character, an aging beauty queen who was crowned in French Guiana in 1955, adorned herself in a gown made from white gloves of the type worn by young ladies in polite society. She appeared several times in the artist’s work between 1980 and 1983. Most famously, she “invaded” exhibition openings at the Black-founded New York City gallery Just Above Midtown (JAM) and the New Museum. She also directed O’Grady’s 1983 parade performance Art Is . . . and curated The Black and White Show at Kenkeleba House, a not-for-profit gallery on the Lower East Side dedicated to showing Black artists. These projects were intended as the first of an open-ended series of Mlle Bourgeoise Noire interventions, but the artist’s need to return to Boston in 1983 to care for her ailing mother interrupted those plans. O’Grady now considers the three projects in this room to be a trilogy, all connected by Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s determination to challenge the art world’s segregation by calling on Black artists to oppose the status quo, demanding white institutions face their exclusion of Black artists and audiences, and asking art viewers and critics to examine their definitions of artistic quality and excellence. -

Mlle Bourgeoise Noire

Mlle Bourgeoise Noire appeared in O’Grady’s first public performances, most famously at the gallery Just Above Midtown (JAM) in June 1980 and the New Museum in September 1981. Designed to directly confront the racial segregation of the art world, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire was a debutante cum racial-justice revolutionary and an equal-opportunity critic, ready to take both the white and Black art worlds, artists, and institutions to task for their shortcomings. Her JAM appearance, at the opening of the exhibition Outlaw Aesthetics, sought to challenge her Black artist peers to take more risks by demanding their place in the mainstream art world. At the opening of the New Museum’s show Persona—which featured an all-white roster of performance artists who, like O’Grady, created characters in their art—she called out the provincial smugness of the white and privileged gatekeepers of artistic culture. At the same time, wearing a gown composed of the white gloves of the polite Black society of her youth and carrying a cat-o’-nine-tails (the “Whip-That-Made-Plantations-Move”), Mlle Bourgeoise Noire comments on both the externally imposed violence and the internalized rules of “respectability” that have kept Black people from achieving freedom. -

The Black and White Show

As Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, O’Grady guest curated The Black and White Show, which ran from April 22 to May 22, 1983, at the Black-operated Kenkeleba House on East Second Street in New York City. The exhibition was a conceptual experiment, in which Mlle Bourgeoise Noire invited fourteen Black artists and fourteen white artists to each contribute a single work composed in black and white. In trying to build a level playing field for viewing and understanding the Black artists’ work, O’Grady, in the guise of her performance persona, intended to make a rational argument for the debilitating limitations of the segregated art world. The Black and White Show offered a deliberate and cogent counterpoint to the emotionally charged entreaty she made in her New Museum performance. Ultimately, as O’Grady later reflected, “its ‘appeal to reason’ had as little effect as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire’s ‘joyous anger.’ The art world’s complexion was the same.” -

Miscegenated Family Album

Composed of sixteen diptychs, Miscegenated Family Album grew out of Nefertiti/Devonia Evangeline. In the 1980 performance of mourning and reconciliation, Lorraine O’Grady paired slides juxtaposing family snapshots of her sister Devonia and her children, with ancient sculptural portraits of the Eighteenth Dynasty queen Nefertiti and her sister. Connecting personal and historical familial narratives across millennia, the artist harnesses the power of the diptych to enrich and humanize parallel stories of sibling love and strife, and points to suppressed narratives of Black Egypt in her own Black middle-class upbringing in Boston.

The edition of Miscegenated Family Album seen here was produced specifically for exhibition display. Edition 6/8 is included in the Brooklyn Museum collection; Purchased with funds given by John and Barbara Vogelstein and Shelley Fox Aarons and Philip E. Aarons and bequest of Richard J. Kempe, by exchange, 2008.80. -

Announcement of a New Persona (Performances to Come!)

A persistent theme in Lorraine O’Grady’s work is the way that Blackness has always been present at the heart of the concept of “the West”—and that, in fact, the West and modernity couldn’t exist without Blackness. This idea propels the artist’s engagement with European art of the modern era in Announcement of a New Persona (Performances to Come!), which blends geographic and cultural forms including the European chivalric tradition, nineteenth-century portraiture, and Caribbean carnival, with its origins in the melding of Black and Indigenous cultures. In these large, staged photographs (which she terms “performances for the camera”), O’Grady is seen dressed from head to toe in custom-made armor, which she designed to include direct references to medieval European examples. The aging Knight sports a helmet that sprouts palm trees and other signifiers of the Caribbean. Announcement also includes a set of “family portraits” showing the Knight with two attendants—a wooden toy horse named Rociavant, and Pitchy-Patchy, a squire based on an amalgam of characters from the carnival traditions of the Jamaican Jonkonnu and Belizean Wanaragua festivals, enacted here by O’Grady’s longtime associate, the artist Sur Rodney (Sur).

-

August 19, 2020

Opening March 5, 2021, Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And will span four decades of the artist’s career and feature nearly all of the artist’s major projects, including the Mlle Bourgeoise Noire trilogy, Rivers, First Draft, and Body Is the Ground of My Experience, plus a wide selection of archival materials on view for the first time. The exhibition will also mark the debut of a much-anticipated new body of work titled Announcement of a New Persona (Performances to Come!).

Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And is the first comprehensive overview of the work of Lorraine O’Grady (b. Boston, 1934), one of the most significant figures in contemporary performance, conceptual, and feminist art. O'Grady is widely known for her radical persona Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, and has a complex practice that also encompasses video, photomontage, concrete poetry, cultural criticism, and public art. The artist has consistently been ahead of her time, anticipating contemporary art world conversations about racism, sexism, institutional inequities, and cultural oversights by decades, and her prescience has inspired younger generations of artists. Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And will mark the first time that O’Grady’s four decades of artistic output will be given its much-deserved institutional credit. The exhibition is curated by Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum, and writer and critic Aruna D’Souza, with Jenée-Daria Strand, Curatorial Assistant, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum.

Raised in Boston by middle-class Jamaican immigrant parents and educated at Wellesley College, O’Grady began her career as a visual artist at the age of forty-five. She previously spent years working as an intelligence analyst for the United States government, a translator, a rock music critic for The Village Voice and Rolling Stone, and literature instructor at the School of Visual Arts. It was, in part, her encounter with Just Above Midtown (JAM) gallery in the late 1970s (and its community of African-American artists and other artists of color) that prompted her to begin her own artistic career. Some of her most important early performances were attempts to lay bare what she recognized as the deeply segregated nature of the art world. At the same time, O’Grady has continually imagined her own history, body, relationships, and biography within a cultural landscape that often erases or obscures Black female subjectivity.

These parallel threads—of outward-facing critique and inward-turning self-reflection—are some of the many binaries that O’Grady’s work addresses. By putting seemingly contradictory ideas into proximity and refusing the possibility of resolution, O’Grady seeks to undermine the power and hierarchy that usually attaches to such oppositions as black and white, museum and individual, self and other, West and non-West, and past and present. The exhibition’s subtitle, Both/And, alludes to O’Grady’s ambitious goal of dismantling the either/or thinking that forms the basis of much of Western thought, and its attendant structural inequalities.

“A Lorraine O’Grady retrospective is long overdue,” says exhibition co-curator Catherine Morris. “For forty years—from the moment she bravely launched herself into the New York art world via the critically astute and unflinching character Mlle Bourgeoise Noire in 1980—Lorraine O’Grady has utilized the tools of the avant-garde to make work prioritizing and valuing her own lived experience as a diasporic subject.” She adds, “We are proud to present the first comprehensive survey of such an important and long underappreciated artist. In addition to holding an important work by O’Grady in our collection, the Brooklyn Museum has featured several of her compelling projects in two recent groundbreaking exhibitions, We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965–85 and Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power. We are so pleased to have this opportunity to further our support of Lorraine’s extraordinary vision and to build her legacy at the Brooklyn Museum.”

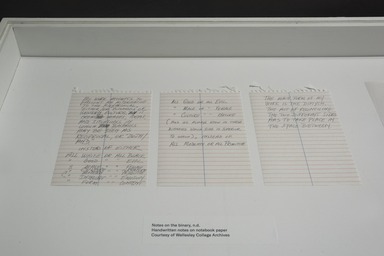

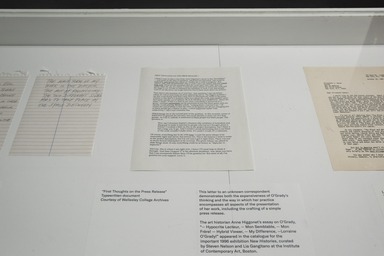

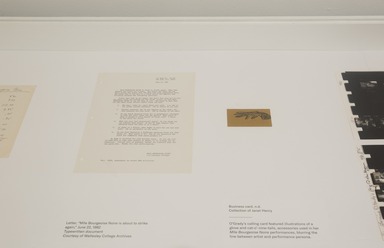

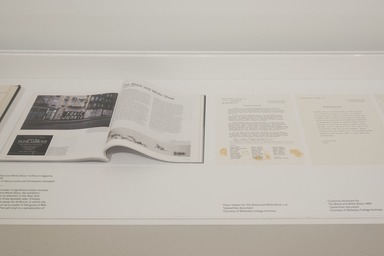

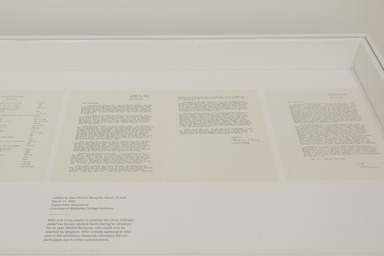

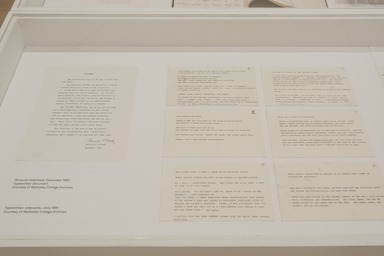

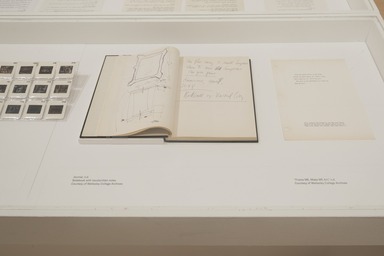

Both/And is organized in six sections; three sections will be located in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, and three in the European Art, Ancient Egyptian Art, and Arts of the Americas galleries located throughout the Museum. These important bodies of work will be embedded in the collections to highlight O’Grady’s long-standing critical engagement with the biases underlying mainstream art historical and cultural institutions. Alongside all of these projects will be a critical selection of materials from O’Grady’s personal archive, which will shed light on the careful decision-making and ambitious intellectual range of her creative process. This ephemera, fastidiously preserved by the artist, is now housed at her alma mater, Wellesley College, and includes correspondence with Adrian Piper, Kobena Mercer, Lucy R. Lippard, and Martha Wilson, along with drafts of writings, journals, interviews, and photographs.

The three sections in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art begin with O’Grady’s 1982 performance Rivers, First Draft, a conceptual source of many of the ideas that would go on to animate the artist’s career. A one-time performance staged in a secluded corner of Central Park before a few dozen spectators, the complex event lives on as a carefully-constructed photo installation. Rivers, First Draft draws upon practices ranging from Dada cabaret and contemporary theatre to West African Vodun symbolism to narrate O’Grady’s own transition from child to teenager to adult artist. The performance speaks to the double bind Black women face, excluded from white spaces because of their race and from Black spaces because of their gender.

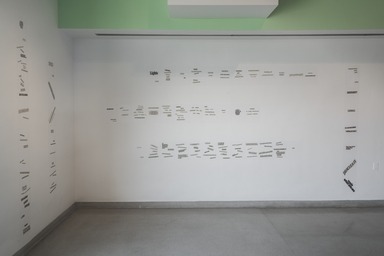

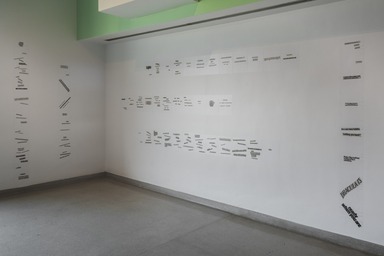

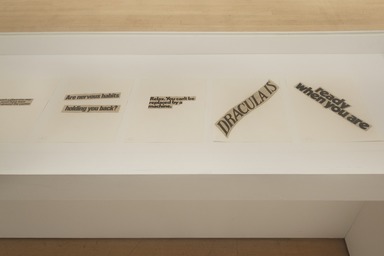

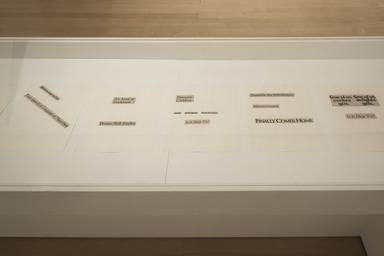

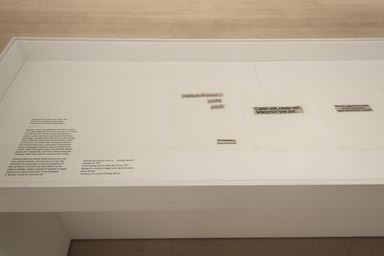

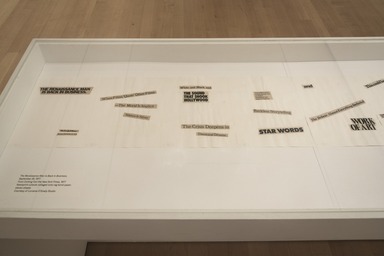

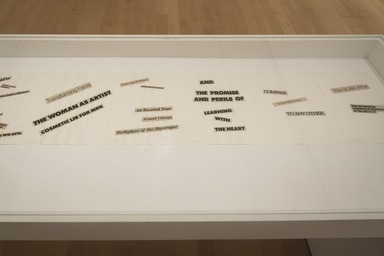

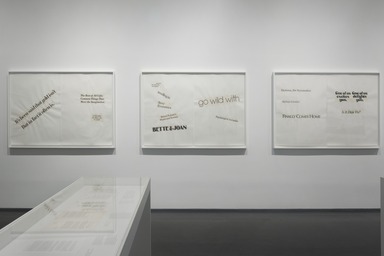

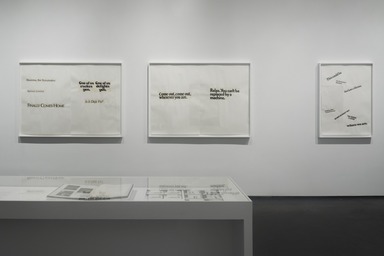

A selection of the original collages from Cutting Out the New York Times (1977) will be on view in the same gallery, and additional examples reproduced in vinyl will be installed throughout the building. Over the course of six months in 1977, O’Grady created her first works of art in the aftermath of a medical crisis, crafting a group of twenty-six highly personal poems from words and phrases extracted from the headlines of the Sunday edition of the New York Times. Both/And will mark the first time the original collage poems will be on public view. Elsewhere in the Sackler Center is Cutting Out CONYT (2017), a recent “remix” of the 1977 Cutting Out the New York Times, which distills the original collage poems into “haikus” in the form of diptychs.

The exhibition’s second section focuses on O’Grady’s critique of the art world’s unexamined cultural assumptions, and the institutional structures it has built to support them. The three projects represented here—Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (1980), Art Is… (1983) and The Black and White Show (1983)—pinpointed the ways in which the art world excluded Black people both as artists and as audiences. O’Grady made each of these works, produced between 1980 and 1983, while in the guise of her performance persona, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (Miss Black Middle Class). The character, an aging beauty queen wearing an evening gown made from 180 pairs of second-hand white gloves, appeared in O’Grady’s landmark guerrilla performances at both Black and “mainstream” (white) cultural institutions in New York City such as JAM and the New Museum. In Art Is…, she responded to a Black acquaintance’s assertion that “avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with Black people” by creating a conceptual artwork for the largest public Black space she could envision: a parade float at Harlem’s annual African American Day Parade. In The Black and White Show, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire invited thirteen pairs of artists—half of them Black, half white—to contribute works in a black-and-white color palette to her exhibition at the important Black-owned Kenkeleba Gallery. In each of these works, the artist’s piercing critique of the racism and sexism of the art world established her as an active voice in the alternative New York art scene.

The third section will feature photocollages from the artist’s series Body Is the Ground of My Experience (1992), including the diptych The Clearing: or Cortés and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me. Perhaps one of O’Grady’s most controversial and misunderstood works, it imagines even the most intimate relationships between Black and white people to be inevitably shaped by the deep history of racism and colonialism in which they occur.

To illuminate O’Grady’s critical engagement with the sweep of art history, a number of projects will be installed in galleries throughout the Museum. In the Ancient Egyptian Art galleries, viewers will have a rare opportunity to see in its entirety Miscegenated Family Album, one of O’Grady’s best-known works and an important part of the Brooklyn Museum’s collection; the 18-minute video installation Landscape (Western Hemisphere) (2010–12) will be sited in the Arts of the Americas; and an exciting new body of work entitled Announcement of a New Persona (Performances To Come!) will premiere in the European Art galleries. The placement of these works in the Museum’s collection galleries provides visitors to Both/And the opportunity to see O’Grady’s work within the art historical contexts that have simultaneously inspired and infuriated her.

The newly-debuted work Announcement of a New Persona (Performances To Come!) will offer a recontextualization of the driving concepts and complex narratives that form the basis of Lorraine O’Grady’s entire career. While much of the project remains secret, O’Grady says that the work consists of a four-part series of character studies in the form of life-size cartes-de-visites for a performance she has been developing since 2013. Though it is a complete work in itself, the series also signals future possibilities for performances and critiques centered around the new persona.

Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And will be accompanied by a catalogue documenting the full span of O’Grady’s artistic career, the first publication to do so. It will include essays by Harry Burke; Malik Gaines; Zoé Whitley; Stephanie Sparling Williams; and the editors, Catherine Morris and Aruna D’Souza, along with a conversation between O’Grady and Catherine Lord. A detailed timeline of O’Grady’s life and career will also be included. Concurrently, a volume of collected writings, Writing in Space: 1973–2019, edited by D’Souza for Duke University Press, will bring together O’Grady’s extensive and important theoretical and critical writings. Conceived in dialogue, the exhibition catalogue and the collection of writings will provide both a robust overview for those unfamiliar with O’Grady’s work, and a valuable permanent resource for those who aim to explore her work in depth.

Lorraine O'Grady: Both/And

View Original