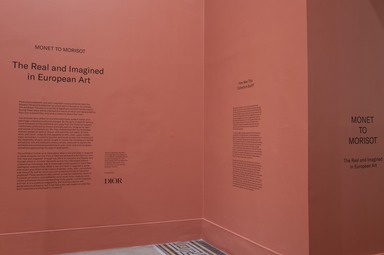

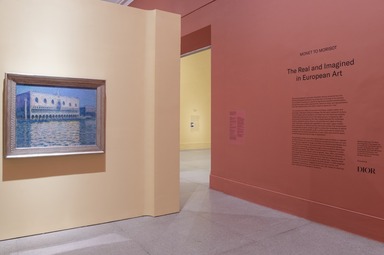

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_01_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_02_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_03_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_04_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_05_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_06_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_07_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_08_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_09_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_10_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_11_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_12_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_13_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_14_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_15_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_16_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_17_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_18_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_19_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_20_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_21_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_22_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_23_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_24_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_25_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_26_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_27_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_28_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_29_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_30_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_31_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_32_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art, Friday, February 11, 2022 through Sunday, May 21, 2023 (Image: DIG_E_2022_Monet_Morisot_33_PS20.jpg Photo: Danny Perez photograph, 2022)

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art

-

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art

Featuring nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artworks from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection by artists born in Europe or its colonies, this exhibition focuses on a period of significant societal transformation. During these years artists explored the nature of vision and representation, their own subjectivities, and what it meant to depict the “real.”

The artworks here reflect an era when technique, subject matter, and patronage underwent profound changes. By the early nineteenth century, some European artists started to turn away from the historical subjects traditionally preferred by church and state patrons. Intrigued by light and scenes of contemporary life, they instead depicted the landscape, ordinary people at work or leisure, and activities and sights of home, work, and travel—subjects that appealed to new urban, upper-middle-class consumers. In colorful touches and broad strokes that emphasized the materiality of paint, artists sought to convey the immediacy of optical sensations. Into the twentieth century, artists continued to explore the aesthetic and emotional possibilities of color, form, and pictorial space, sometimes approaching the edge of abstraction.

The exhibition invites us to think about what is real and what is imagined in these artworks not only from a historical perspective but from our own. The “real and imagined” through line offers an evocative and flexible lens through which to consider the works across five interrelated themes, unbound by chronology, and to encourage critical questions about their ideological underpinnings: What is real and what is imagined in works that assert and reflect certain views of gender, class, labor, colonialism, and nature? By and for whom are such collective frames of reference produced? These questions also remind us that the traditional canon of European art history, exemplified by many works here—made by white artists and almost exclusively depicting white people—is both imagined and real. It is a construct imagined by and serving a narrow, self-designated constituency, but it has had a very real impact on what has been collected and displayed in museums.

How Was This Collection Built?

Like most U.S. collections built during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Brooklyn Museum’s European holdings from this period consist primarily of works by white male artists, with only a handful by women artists and none by artists of color. This lack of diversity reflects historical sociopolitical forces, not European demographics at the time. Unequal power relations determined who had access to the training, opportunities, and financial support necessary to become a successful artist. Institutional, curatorial, and academic biases over time also defined the type of artists and artworks deemed worthy of exhibiting and collecting.

The Museum began acquiring European art from this period at the beginning of the twentieth century. Founding supporters bought artworks from dealers and auctions and gave them to the institution, while other initial acquisitions were purchased with funds donated by the public. In the 1920s Brooklyn demonstrated its commitment to modern French art by being the first museum in New York City to add to its collection paintings by Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec—considered bold acquisitions at the time. Over the years the Museum also exhibited and acquired modern works by artists from European countries other than France, including Belgium, Croatia, Germany, Hungary, Spain, and Russia.

Throughout the twentieth century the Museum’s collection of European art continued to expand through designated purchase funds or, more often, gifts. These came from individuals whose philanthropy was made possible by earned or inherited wealth from businesses such as finance, entertainment, real estate, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and sugar (the last built on enslaved African labor in the Caribbean). Much of Brooklyn’s European modern collection reflects the taste of these white, urban, mostly male donors, and the centrality of nineteenth-century France in the art historical canon. Today, the Museum’s priority is to build a more artistically and thematically diverse and inclusive European art collection through which we can continue to explore the dynamics of race, gender, class, and colonialism.

Posed and Composed

Portraits and still lifes engage with the complexities of likeness, whether that likeness is visual, psychological, or symbolic. Bourgeois patrons posed for fashionable portraits that signaled their social and economic status and were potentially lucrative commissions for artists competing in a newly independent art market. Artists also made psychologically resonant portraits of family and friends in familiar spaces, often inflected by memory, as well as still lifes of objects that project emotional intensity. Favorite models posed in costume convey a double likeness, recognizably themselves while also representing an imagined “type.” In the twentieth century, some avant-garde artists traded optical verisimilitude for abstraction or stylization.

Near and Far

Artists portrayed places, times, and social milieus that they perceived as distant from their own and from those of their urban bourgeois patrons. In the nineteenth century European artists frequently envisioned contemporaneous non-European peoples as not only physically remote but fixed in an unchanging past. Such “exotic” imagery reduced vast regions and different cultures to monolithic, disparaging stereotypes. Some artists traveled to Egypt and the Ottoman Empire, destinations made accessible to them by European imperialist and colonialist incursions. But they created their paintings in the studio, using clothing and objects collected during their travels as props—collapsing the space between near and far, and between the real and the imagined.

Likewise, mythological subjects, pastoral scenes of idle pleasure, or even images of European peasant figures in traditional regional attire all evoke a timeless elsewhere, though they were often posed by costumed professional models, performers, or an artist’s friends or family.

Performing Labor

Concerns about the effects of industrialization and urbanization on rural life intensified in Europe after the revolutionary upheavals of 1848. By the 1850s rural labor had become a significant theme in European art, particularly in France. Critics interpreted representations of these working rustic figures as dignified, animalistic, spiritual, bleak, contented, or dangerous, depending on their own fears or political inclinations. Looking at these images at a time of social and political flux, and primarily from an urban vantage point, many collectors in France and in the United States were reassured by visions of what they imagined as an eternal, stable countryside and its unthreatening inhabitants.

The predominantly female performers and servers of the urban entertainment economy were also a popular focus for male artists, who encountered them throughout Parisian nightlife. Studio models who posed for artworks were workers, too, employed by artists who themselves had to find ways to promote and exhibit their wares in a new and changing art market.

Faith and Conflict

Even as depictions of ordinary and secular daily life came to prominence in the nineteenth century, European artists continued to grapple with visualizing faith, spirituality, political conflict, and the psychic toll of war. They created public monuments that communicated themes of revolution or anarchy through the language of allegory. Using vibrant colors or stylized forms, they imagined biblical narratives as subjective, dreamlike interludes. Other artists pictured devout peasants whose poverty and simple virtue, according to the Catholic Church, made them inherently closer to God. Women were believed to be especially pious, and paintings featuring them at prayer or within a humble familial context were particularly appealing to collectors in the nineteenth century.

In the twentieth century, after the horrors and dislocations of two world wars, artists experienced crises and reaffirmations of faith, conveying their feelings about the human condition with emotional immediacy and impact.

Picturing Nature

Landscape painting became a vital field for formal experimentation in the nineteenth century as artists sought to materialize their perceptual experiences of light and space. Traditional training encouraged artists to sketch outside and use those studies to develop finished landscape compositions for exhibition. By the 1830s artists (and later, the public) embraced the sketch aesthetic—a taste for loosely rendered, unidealized images free of historical or literary associations—in works they considered complete. Such energetic brushwork became identified with individuality and immediacy of vision and execution, although many artists still finished their paintings inside the studio.

Landscapes also embodied various intersecting subjectivities. In the nineteenth century open-air sketching was an almost exclusively male practice, since painting outside, often in isolated areas, was not socially acceptable for women. Artists painted their own property or familiar regions: sites of work and leisure such as the Forest of Fontainebleau; popular destinations, including the Normandy coast, where they joined other urban tourists experiencing “nature”; and imagined dreamscapes. Human presence or intervention and the impacts of industrialization on the natural world are apparent in some paintings, while others reference geological forces or atmospheric conditions.

-

January 6, 2022

Opening February 11, 2022, the new thematic reinstallation of the Museum’s renowned holdings of nineteenth- and twentieth-century European art features nearly ninety important paintings, sculptures, and works on paper, many of which have not been on view together in Brooklyn since 2016.

Monet to Morisot marks the reinstallation of the Brooklyn Museum’s collection of historic and foundational works of European art made by artists born in Europe or its colonies, highlighting nineteenth- and twentieth-century selections by artists including Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Berthe Morisot, Francisco Oller, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Gabriele Münter, Yves Tanguy, and Vasily Kandinsky. Casting fresh eyes on the collection, this presentation explores not only the profound and ongoing influence of modern European art, but also how the art historical canon itself is a site of tension. Many of these works are on view together in Brooklyn for the first time since 2016, when they began touring the United States and Asia in the acclaimed exhibition French Moderns: Monet to Matisse, 1850–1950.

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art is curated by Lisa Small, Senior Curator, European Art, with Shea Spiller and Talia Shiroma, Curatorial Assistants, Arts of the Americas and Europe.

“It’s thrilling that so many of Brooklyn’s extraordinary holdings of modern European art, including some of our earliest acquisitions by Degas and Cézanne, are going back on view in a beautifully designed space where visitors can experience them anew, alongside rarely seen ‘discoveries’ by artists like Chana Orloff and Ivan Meštrovic,” says Lisa Small. “I’m particularly excited about the opportunity that this and future European art presentations provide to reexamine and expand the stories we can tell with these objects, to make connections across all of the Museum’s collections, and, most importantly, to think critically about what and who is missing.”

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an era of significant social and artistic transformation, artists moved away from traditional forms of representation to portray scenes from ordinary contemporary life. They began to explore the nature of vision as well as their own subjectivities in works that increasingly appealed to new urban, upper-middle-class consumers. This exhibition’s throughline of “real/imagined” offers an evocative and flexible lens through which to consider the nearly ninety paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures across five interrelated themes of portraiture, “exoticism” and “primitivism,” labor, faith and conflict, and landscape. These works are organized nonchronologically and encourage critical questions about their ideological underpinnings, such as: What is real and what is imagined in works that assert and reflect certain views of gender, class, labor, colonialism, and nature? By and for whom are such collective frames of reference produced?

Broadly, the presentation reminds visitors that the traditional canon of European art history, exemplified by many of the works on view—made by white artists and almost exclusively depicting white people—is both imagined and real. It is a construct imagined by a narrow, self-designated constituency, which has had a real impact on what museums such as the Brooklyn Museum have chosen to collect and display for decades.

Monet to Morisot: The Real and Imagined in European Art

View Original