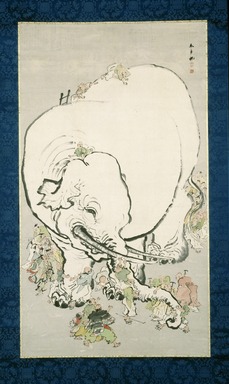

Artist:Ohara Donshu

Medium: Ink and colors on paper

Geograhical Locations:

Dates:early 19th century

Dimensions: Overall: 92 x 46 1/2 in. (233.7 x 118.1 cm) Image: 67 x 37 1/2 in. (170.2 x 95.3 cm)

Collections:

Accession Number: 1993.57

Image: 1993.57_IMLS_SL2.jpg,

Catalogue Description: The painting represents a large, benevolent, white elephant being examined by a group of figures, many of them blind. The blind men acquaint themselves with the elephant by touch, while those who can see either laugh at the event taking place in front of them or quietly queue up to take their turn to inspect it. The scene, known from sources throughout Asian literature and painting, is a metaphor for the human condition: each individual presumes to know the nature of the universe through his extremely limited personal experience of it. The subject is found in "Sketchbooks of Hoksai" ("Hokusai Manga") (1814-19), where a hulking elephant is shown in profile surrounded by miniscule blind figures. One blind man touches the trunk and exclaims: "Why an elephant is like a snake." Another, its tail: It's like a rope." Another, it's flank: "Like a wall." Expressive figures of blind men are frequently employed in later Japanese Buddhist painting to represent the vulnerable and precarious condition of those who are spiritually blind. The subject of blind men examining an elephant is found as early as the fifth century A. D. in the "Hitopadesha," the Indian version of Aesop's fables. The composition in the Donshu work closely follows an earlier Chinese precedent called "Washing the White Elephant," which we know from several late Ming examples, such as a painting by Ding Yungpeng of 1604, representing the annual event in China when the imperial court elephants were ritually cleaned (Hyland, "Deities, Emperors, Ladies and Literati; Figure Painting of the Ming and Qing Dynasties," Birmingham Museum of Art, 1987: Alabama, cat. # 20). Hokusai also treated this subject in Vol. 13 of the "Hokusai Manga" (c. 1849-50) (Hillier, "Hokusai Manga," fig # 40) although in Hokusai's version, the elephant is seen in profile. A more contemporary inspiration for later Japanese artists may have been the actual arrival in Japan, in 1978, of a white elephant brought from Siam, an event that appears to have generated a great deal of excitement. Ohara Donshu is a Kyoto painter of the Shijo School known for his wide variety of subjects and varied techniques. He is not, however, a typical Shijo painter. His work is sufficiently rare. Three paintings in the Ogino Collection, Kurashiki, Japan have been published: "A Fan Painting of Immortal Kinko" (The Suntory Museum Catalogue) Lady Playing a Zither; and the Chinese Literati landcape subject Lan-ting Pavilion. Donshu's abbreviated style can be associated with the haiga genre which is know for a sketchy, spontaneous technique often associated with haiku poems. Jack Hillier praises Donshu's work as a haiku illustrator and cites three additional paintings in Japanese Collection (Yabumoto and Richard Lane). Even more impressive than the published examples, the monumental scale of this painting is enhanced by the artist's detailed depiction of the elephant in dry brushwork and the animated figures surrounding it. He blurs the dry color applied to several patches of the figures' costumes, rather than laying it down in flat tints. The background is deliberately worked in serene gray washes. The painting came with an original wooden box on which the title "Elephant" and the artist's name "Donshu-hitsu (painted by)" were written. Condition: Good. There is scattered foxing throughout the paper and the green pigmants (probably of copper origin) have stained the paper where in contact. (See Record of Restoration File).