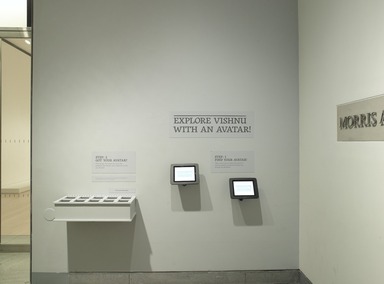

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_01_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_02_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_03_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_04_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_05_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_06_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_07_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_08_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_09_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_10_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_11_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_12_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_13_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_14_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_15_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_16_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_17_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_18_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_19_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_20_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_21_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_22_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_23_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_24_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_25_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_26_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior, June 24, 2011 through October 2, 2011 (Image: DIG_E_2011_Vishnu_27_PS4.jpg Brooklyn Museum photograph, 2011)

Vishnu: Hinduism's Blue-Skinned Savior

-

VISHNU: HINDUISM'S BLUE-SKINNED SAVIOR

Hinduism is an ancient and complex religion, constantly evolving as it absorbs and reinterprets many different belief systems. Hinduism is polytheistic, with thousands of different gods and goddesses. Over time, three deities—Vishnu the Preserver, Shiva the Destroyer, and Devi the Great Goddess—have attracted large sectarian followings. For his or her worshippers, the favored deity is the Supreme Power, who is served by all other gods; alternately, the many gods are understood as diverse aspects of the primary deity.

Among the three supreme deities, Vishnu is the most multifaceted, and his character and nature have grown more complex with each century. Although he is celebrated as the great creator of the cosmos, he most often serves as its preserver, descending to save the world—and lesser gods—from powerful demons and other threats. He assumes many different shapes in his quest to maintain order, including a number of limited, earthly bodies called avatars. Although the avatars have individual talents and personalities, they are usually said to share Vishnu's signature skin tone: the blue distinguishes them from mere humans, and it reflects the god's association with the vast expanses of sea and sky as well as his usually cool, tranquil approach to saving the world.

Vishnu has been worshipped for more than two thousand years throughout India, and today his devotees, known as Vaishnavas, can be found all over the world. The god and his avatars have been the inspirations for countless great works of art and literature. This exhibition focuses on works of art from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh and is organized by theme, with objects in radically different forms, styles, and media appearing together. It offers an introduction to the sophisticated artisanal practices that developed in varied regions over the course of about 1,600 years while revealing the many ways that one of Hinduism's most important deities was portrayed and celebrated.

Joan Cummins

Lisa and Bernard Selz Curator of Asian Art -

IMAGES OF VISHNU

In Hinduism, supreme deities such as Vishnu are thought to be so vast, varied, and brilliant that their form is incomprehensible to mere mortals. These deities reveal themselves to devoted followers in smaller, more approachable bodies. It is these forms that appear in art. Most depictions of Hindu gods look like humans, but better, with special physical traits that reflect their superior powers.

When Vishnu reveals himself in his primary form, he always has blue skin. While this feature is not portrayed in most stone and bronze sculptures, other identifying characteristics are included. Vishnu wears the tall crown, jewels, and wrapped skirt (dhoti) of an early Indian prince. He often has more than two arms: extra hands represent the ability to do many things and to reach in many directions at once. He holds his preferred weapons and emblems: conch shell, discus, lotus, and mace. Whereas other gods are shown swaying gracefully, Vishnu stands straight, a reference to his role as a maintainer of balance. -

VISHNU'S ATTRIBUTES

In Hinduism, all deities wear or carry special objects that signify aspects of their individual personalities and allow us to identify them. In addition to his blue skin and straight posture, Vishnu can be identified by the four objects he holds. Most gods and goddesses carry a favorite weapon that they use in battles against demons: for Vishnu these are the discus or wheel (called a chakra) and the mace. Vishnu blows the conch shell like a trumpet, while his lotus is an emblem of transcendence. Occasionally one of the objects will be omitted in a representation of Vishnu so that he can make an expressive hand gesture, known as a mudra, signifying reassurance or the granting of wishes.

For the worshippers of Vishnu, the god’s four attributes are so important that sometimes they are revered as separate deities. Vishnu is the only Hindu god whose attributes are personified in images, shown as servants standing at his side. -

THE CONSORTS AND FEMALE FORMS OF VISHNU

Hinduism identifies the masculine with the intellect and spirit, and the feminine with emotions and physical energy. The two are complementary and necessary to the well-being and continuity of the cosmos. There are many goddesses in Hinduism. Some are powerful warriors, while others are loving wives and mothers. Icons that depict the gods with their wives allow the worshipper to celebrate masculine and feminine aspects of the divine at the same time.

Most Hindu gods have at least one wife, whose personality reflects and balances that of the god. Vishnu’s primary consort is Lakshmi, an extremely popular goddess who promotes wealth and good fortune. Vishnu is sometimes shown with two wives, Shri Devi and Bhu Devi, who are really Lakshmi split into two complementary parts. It could be said that while Vishnu tends to the well-being of the cosmos, his wives tend to the more humble daily needs of mankind.

Distinct from the worship of wife or consort goddesses is a more esoteric tradition in which the feminine aspect (shakti) of each major Hindu god takes form as a separate goddess. Vishnu’s feminine manifestation is a volatile goddess called Vaishnavi. -

GARUDA

Every Hindu deity has an animal that he or she rides: Shiva has a bull, Durga has a lion, and Vishnu has an eagle, whose name is Garuda. These animal vehicles reflect aspects of the god’s character. A figure of a deity’s animal mount is often enshrined just outside the entrance to the god’s temple to face the icon of its master.

Like Vishnu, an eagle swoops down to earth from above, attacking enemies with deadly precision. Images of Vishnu mounted on Garuda usually show the exciting moment when the god appears from above to save the day. Garuda is often depicted as part-man, part-bird, with a human face and arms but with wings, talons for feet, and a beaklike nose. With his speed, strength, flying power, and unswerving dedication to his lord, Garuda has been a popular emblem for kings and their armies for millennia, and the bird can be found on flags, thrones, and airline logos from Mongolia to Bali. -

THE LEGENDS OF VISHNU

The objects in this section illustrate narratives that reveal the great scope of Vishnu’s power and influence. Usually when he descends to earth, Vishnu takes the more limited form of an avatar, but at the moments of cosmic creation and destruction, and in select rescues, he acts in his primary form.

In the Indian tradition, painting is far more likely than sculpture to play a storytelling role, so in this section dedicated to narratives of the legends of Vishnu we will begin to see fewer sculptures and more paintings. There were three major types of painting in premodern India: murals (not represented in this exhibition), large-scale paintings on cloth, and smaller paintings on paper. The paintings on cloth were either displayed temporarily in temples or used by bards to provide visuals for storytelling performances. The paintings on paper often served as illustrations for texts, sometimes bound into manuscripts; many shown in this exhibition were originally part of large series. They are sometimes called miniature paintings, but many are actually quite large. -

THE AVATARS OF VISHNU

Vishnu’s most distinctive trait is his choice to act through avatars. These earthly manifestations are less glorious than the god, have finite bodies, and are usually mortal. Vishnu’s descent from the heavens in the form of an avatar may be compared to his reaching his hand down: the hand is fully Vishnu, but it is not the god in full.

Most Hindu texts list ten avatars: nine past avatars and one scheduled to arrive in the future. Some Hindus believe that Krishna is more than a mere avatar and do not include him on the roster. The most commonly depicted avatars are the following:

MATSYA the fish

KURMA the tortoise

VARAHA the boar

NARASIMHA the man-lion

VAMANA the dwarf

PARASHURAMA the Brahmin

RAMA the king

KRISHNA the cowherd prince

BALARAMA the brother of Krishna

BUDDHA the preacher

KALKI the avatar of the future

When all ten avatars are shown together, often as small figures surrounding a central image of Vishnu, they serve as illustrations of the god’s manifold powers, or as a celebration of the many times that Vishnu has saved the world.

-

THE MATSYA AVATAR

Vishnu’s first descent to earth, then a new world consisting primarily of oceans, was as a fish, named Matsya. Although he receives relatively little attention from worshippers, Matsya is celebrated for two heroic deeds.

In one story, Matsya is summoned by the god Brahma, who is the keeper of the Vedas, Hinduism’s most ancient scriptures. A demon named Hayagriva has stolen the sacred texts and hidden them at the bottom of the ocean. Matsya defeats Hayagriva and returns the Vedas to their rightful guardian.

In the second story Matsya saves Manu, the progenitor of all men, from a great flood. Manu finds a small fish and takes care of it until it grows to an enormous size. The fish reveals himself to be an avatar of Vishnu and then rewards Manu by warning him that a great deluge is coming. He tells Manu to bring the most learned Hindu sages, plus two of each type of animal, aboard a boat and tether it to the great fish. With Matsya’s help, Manu and his passengers survive to repopulate the earth. -

THE KURMA AVATAR

Among Vishnu’s avatars, Kurma the tortoise has the least developed personality, and as a result he is probably the least worshipped. However, the tortoise (also called a turtle) participates in one of Hinduism’s most important stories.

The legend begins not long after Creation, when an influential sage cursed the gods, causing them to lose some of their powers to the demons. The gods appeal to Vishnu, who tells them to churn the ocean much as people churn cream for butter. They tie a giant snake, Vasuki, around a mountain and pull back and forth on it, causing the peak to rotate like a churning paddle. Vishnu becomes Kurma the tortoise to support the spinning mountain on his back.

The churning produces fourteen magical things, including the nectar of immortality. The gods and demons are supposed to share the nectar, but Vishnu fools the demons out of their portion; as a result, the gods become immortal and the demons do not. -

THE VARAHA AVATAR

Vishnu descends as Varaha at the request of Manu, the ancestor of men, because the earth is sinking into the ocean. The Varaha avatar is a giant wild boar, a form suitable for digging down into the water in order to sniff out the earth beneath. Indian hunters have long admired wild boars for their strength and bravery, and Varaha is treated as a dashing superhero, with a muscular body and gallant personality.

Varaha dives into the ocean, grabs the earth—usually shown as the goddess Bhu—and emerges, usually with the goddess hanging from one of his tusks or seated on his shoulder. He places the earth on the surface of the ocean, where she remains to this day. In many accounts, Varaha also battles and defeats a demon named Hiranyaksha, who wants the earth to drown.

Varaha is one of Vishnu’s most popular avatars. The boar appears prominently among the sculptures on Vishnu temples and sometimes has temples of his own. -

THE NARASIMHA AVATAR

Vishnu assumes the hybrid form of the man-lion Narasimha in order to kill a powerful demon named Hiranyakashipu. As is often the case with Vishnu’s demon foes, Hiranyakashipu starts off as a dedicated practitioner of yoga and meditation. The god Brahma rewards the demon by granting his wish that he be invincible by man or beast, indoors or out, on earth or in the heavens. Hiranyakashipu then wreaks havoc, so the gods turn to Vishnu for help.

The demon’s son, Prahalada, is a devout worshipper of Vishnu. Mocking his son’s dedication, the demon asks, “If Vishnu is everywhere, is he even in this column holding up the roof?” When the son answers yes, Hiranyakashipu kicks the column and Vishnu instantly emerges from it in a ferocious form, with the body of a man and the teeth and claws of a lion. Narasimha—who is neither man nor beast—drags Hiranyakashipu to the threshold—neither in nor out—and places him upon his divine lap—between earth and heaven. He rips open Hiranyakashipu’s abdomen and pulls out his entrails, putting an end to the demon’s reign of terror.

The most fearsome of Vishnu’s avatars, Narasimha nevertheless enjoys a relatively large following, and Indian warriors have long compared themselves to him. -

THE VAMANA AVATAR

In his first fully human avatar, Vishnu comes to earth as a dwarf in order to defeat a demon named Bali. After making elaborate ritual sacrifices and honoring Brahmin priests in exchange for their blessings, Bali gains excessive power. When he seizes the kingdom of heaven, the gods go to Vishnu for help.

Vamana dresses in the humble clothes of a young Brahmin scholar and approaches the demon, who asks him what he might do to gain the Brahmin’s favor. Vamana asks him for a parcel of land, only as big as he can cover in three steps. Bali grants the apparently puny request, whereupon the dwarf reveals himself to be Vishnu, gigantic and powerful. The god takes three steps, covering all the earth with the first, all the sky with the second, and all the heavens with the third. Vishnu becomes master of all creation and Bali loses everything, although Vishnu later gives him a small kingdom to rule.

Trivikrama, Taker of the Three Steps, is perhaps Vishnu’s most ancient identity, celebrated in the first Hindu scriptures. -

THE PARASHURAMA AVATAR

Parashurama, the vengeful Brahmin, is perhaps Vishnu’s least sympathetic avatar, but he represents an ancient and important Hindu belief in the necessity of maintaining order and balance among the classes, or castes. He descends because all of earth’s kings, who are members of the warrior (kshatriya) caste have become intoxicated with their own power and are failing to acknowledge the superiority of the priestly or Brahmin caste.

Born to the sage Jamadagni and his wife Renuka, Parashurama proves his unyielding sense of right and wrong at an early age. Later, King Kartavirya, a member of the warrior caste, visits Parashurama’s family compound and steals their most prized possession, a wish-granting cow. The Brahmin tracks down the king and kills him by cutting off the king’s many arms. The king’s sons avenge Kartavirya’s death by killing Parashurama’s elderly father. Parashurama then dedicates his life to the punishment and humiliation of the warrior caste. -

THE RAMA AVATAR

Rama the prince is one of Vishnu’s most important and revered avatars. He is the hero of the Ramayana, an immensely popular epic recorded in Sanskrit about 300 b.c.e. and later retold in many Indian dialects and in countless pageants, films, and television series.

Rama is born on earth as a prince to defeat the demon king Ravana, who had been granted a wish that he would be invincible by man or god (but not by a man-god). Political machinations cause him to be exiled to the wilderness, where he lives happily in the forest with his wife, Sita, and brother, Lakshmana. When the king of the demons, Ravana, kidnaps Sita, Rama locates her with the aid of a clan of monkeys. After a long war, Rama’s troops vanquish the demons. Then the term of his exile ends, and he assumes his father’s throne and rules well for many years.

Levelheaded, brave, and morally blameless, Rama became a model for all Hindu kings and for the royal courts of several Southeast Asian countries as well. Nevertheless, he did not enjoy a strong sectarian following until the fourteenth century or later, and there are few if any early temples dedicated solely to him. Today he is adored by many as a promoter of Hindu values and a foe to enemy invaders. -

HANUMAN

Rama’s most helpful ally, the monkey general Hanuman, is one of Hindu literature’s most delightful characters. Hanuman is the son of the wind god, but he retains many monkey characteristics, including the ability to leap long distances and a playful, even mischievous quality that serves as a foil for Rama’s upright seriousness.

Hanuman jumps across the ocean to Lanka to find Sita; he sets the demon capital ablaze; and he retrieves an herb from the Himalayas to heal the wounded Rama and Lakshmana. In later versions of the story, he emerges as Rama’s greatest devotee.

Hanuman was not widely worshipped until recently, but today he is extremely popular as the possessor of magic powers of healing and good fortune. His devotees come from every sector of Hindu society, and much of Hanuman worship has little or nothing to do with worship of Vishnu. -

KRISHNA AS AVATAR AND GOD

Krishna appears in early lists of the ten avatars, but later he is often replaced by his brother. This is because Krishna attracted a very wide following, and his devotees consider him to be more than an avatar, equivalent or identical to Vishnu, the god in full.

Krishna’s earthly biography is more extensive and detailed than that of any other avatar, even Rama. Krishna is born into a royal family but his parents send him to be raised in the countryside to protect him from a murderous uncle. It soon becomes clear that Krishna is superhuman, and he is much beloved by his adoptive community. He spends his youth carousing in the pastures and fighting the occasional demon. He eventually leaves the cowherds, kills his uncle, and assumes his rightful throne. The Bhagavad Gita, one of Hinduism’s most important scriptures, is preached by Krishna during this mature period.

As Krishna grows older, his divine charisma makes him irresistible to women. Devotees of Krishna often use romantic love as an analogy for their feelings about the god, and Krishna’s relationship with his favorite milkmaid (gopi), Radha, is explored in great depth by India’s poet-saints.

Few temples or sculptures were dedicated to the god before about 1000 c.e. Since that time, however, Krishna’s devotees have become some of India’s most avid patrons of the arts. -

THE BALARAMA AVATAR

When Balarama is included in lists of Vishnu’s avatars, he is celebrated almost entirely as Krishna’s older brother. Nevertheless, Balarama has ancient origins as a hero-deity with a complex personality.

As a child, Balarama is sent to the same pastoral community that Krishna subsequently joins, and the two grow up together. In paintings Balarama is identified by his white skin. Many accounts say that Krishna is the incarnation of Vishnu, while Balarama, his lifelong supporter, is the incarnation of Vishnu’s giant serpent, Shesha, on whom the god reclined while creating the cosmos. Because of Balarama’s association with Shesha, he is often depicted with a cobra hood behind him.

Krishna is mischievous, but he rarely makes mistakes; Balarama, by contrast, is sometimes too impulsive. His signature deed, performed after Krishna has left the cowherds, is the plowing of the Yamuna River. Balarama is usually depicted holding a plow, shaped like a long sickle or hook. This attribute appears in the most ancient images of the god, suggesting his origins as an agrarian deity. -

THE BUDDHA AVATAR

According to some texts, Vishnu’s ninth avatar is the Buddha, ancient founder of the Buddhist religion. He is the only avatar who can be traced to a historical period, about 500 b.c.e., when, as an Indian prince named Siddhartha, he preached an alternative to Hinduism.

The Buddha avatar is not a recognition or absorption of the rival religion’s ideas. Rather, his story asserts that Hinduism, not Buddhism, is the true religion. The Buddha avatar descends to defeat a group of demons and other lowly types who have gained too much power through study of sacred Hindu texts. He convinces them to embrace the new creed and reject the Hindu teachings, causing them to lose their power.

The Buddha avatar receives little attention among Hindus. He is usually depicted simply standing or sitting; paintings often show him as a temple icon on an altar, receiving worship. -

THE KALKI AVATAR

Vishnu’s final avatar has not yet arrived. Hindus believe that we are currently living in a decadent period, when all that is good in Creation is gradually dissolving in preparation for the great Destruction that will end it all.

The last avatar, Kalki, will usher in the end of this phase and the beginning of the new, better era. He will be born to a Brahmin family and trained under an earlier avatar, Parashurama, who is said to remain on earth. The god Shiva will grant Kalki a white horse that can change its shape, a parrot that knows everything about the past and future, and a powerful sword. Kalki will battle the forces of delusion and sloth, saving a handful of righteous individuals to repopulate the earth.

Kalki is not extensively worshipped except as part of the larger group of avatars. He is always depicted with his horse and sword. -

MULTIFACED VISHNUS

Even among the very earliest Hindu sculptures we find images of Vishnu with four faces. The central face is that of his primary form, placid and apparently human. The faces at either side are usually those of a boar and a lion. Sometimes there is another face at the back, or it is simply implied. The identity of these complex figures is a matter of considerable debate among modern scholars. It is likely that different images have different identities, depending on where they were made, or that their meaning has changed over the years.

Multiheaded Vishnus are usually identified as representations of Vaikuntha, a form of Vishnu that combines the many avatars in a single body. In this interpretation, the boar and lion heads are understood to be the avatars Varaha and Narasimha. In addition, however, early texts celebrate a four-fold form of Vishnu that has little if anything to do with the avatars. Vishnu is said to have created four successive versions of himself, called vyuhas, each less vast and ethereal and therefore easier to comprehend than its predecessor. According to the texts, the fourth vyuha, the smallest and most concrete, creates the universe. -

WORSHIPPING VISHNU

Vishnu assumes many different forms to address the needs of the cosmos. Similarly, his worship assumes varied forms in accordance with the needs of his followers. Hinduism is ever evolving, adding new ideas and practices in response to the teachings of influential religious leaders, local traditions, and economic, political, and technological change.

This section includes images that depict the people who pray to Vishnu and the places where they pray, as well as the objects that they have used during prayer. The diverse selection of objects barely scratches the surface of Vaishnava tradition. Many visual forms are not represented here, and there are numerous Hindu practices that do not involve the use of art objects. These include meditation and yoga, Vedic sacrifice, the study of sacred texts, music and dance, charitable acts, and any number of daily prayers, annual festivals, and rites of passage that are performed in homes throughout the world using nothing more than a pot of water or the flame from an oil lamp. -

SHRI NATHAJI

Beginning in the fifteenth century, devotees of Krishna identified a small group of figures of the god as earthly manifestations of the divine, something like avatars in sculptural form. The most celebrated of these miraculous icons is Shri Nathaji, an image of Krishna raising Mount Govardhana above his head with one hand. This icon is enshrined in a large temple at Nathadwara, where it is worshipped during a rigorous schedule of festivals and rites, each accompanied by elaborate decoration of the shrine area.

The signature method for decorating Shri Nathaji’s shrine is the picchawai, a large painted cloth that hangs behind the icon, usually decorated in a manner pertinent to a season or holy day. Most of these picchawais were made by workshops of artists located near the temple. These same artists also developed a thriving industry making small paintings and picchawais as souvenirs for pilgrims. Featured at the center of these images is Shri Nathaji, a distinctive black stone figure with bright white painted eyes, usually dressed in seasonal clothing. -

POPULAR PRINTS

At the end of the nineteenth century, Indian publishers began to mass-produce inexpensive, full-color images using the new technology of chromolithography. The best-selling images were those of Hindu deities, and many were installed in home and office shrines. Although some publishers enlisted traditionally trained artists to design their images, many employed painters who practiced the Western styles that were being taught at new art schools in India’s major cities. Proficient in oil painting and one-point perspective, these artists created compositions that combine Hindu subject matter with Western pictorial conventions.

Literally thousands of chromolithographs have survived from the first half of the twentieth century. Many are close copies of previously released compositions and many were poorly printed. The Vaishnava images shown here were selected for their artistic merits and for the novel or unusual treatments of their subject matter.

-

March 1, 2011

Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior will feature more than 170 objects that will explore the many personae and legends of Vishnu, his entourage, and his accoutrements, as well as the diverse traditions of worship related to him. This large-scale exhibition includes Indian sculpture, paintings, textiles, and ritual objects that range in date from the fourth century C.E. to the twentieth century and will be on view June 24 through October 2, 2011, at the Brooklyn Museum. The exhibition will include sixteen objects from the Brooklyn Museum’s permanent collection.

Vishnu, one of the most important gods in Hinduism, is often described as part of a trinity consisting of Brahma the Creator, Vishnu the Preserver, and Shiva the Destroyer. He is responsible for maintaining balance in the universe and is often depicted in a serene and peaceful state. Visual representations often depict him with four arms, signifying strength and the ability to engage in many activities simultaneously, as well as a blue skin tone that associates him with the cool expanses of water and sky. Vishnu is believed to assume other forms, called avatars, which allow him to descend to earth to fight the forces of chaos and to protect humankind.

The exhibition is organized thematically and will be divided into three main sections. The first is an introduction to Vishnu featuring his emblems; his wives and female manifestations; his eagle mount, Garuda; and legends recounting his role in creation. This introductory section includes sculptures of Vishnu, one of which is a large-scale terracotta of the god standing alone. Most gods in Hinduism are portrayed in a swaying posture, but Vishnu is almost always shown standing upright to symbolize the balance he brings to the world. Also included in this section is a tenth-century sandstone sculpture of the god reclining on a giant serpent, depicting the moment of Creation.

Every Hindu deity has a female counterpart; in Vishnu’s case this is his consort, Lakshmi, who is portrayed along with Vishnu in many of the works on view, often in affectionate poses. In an elaborately carved stele, Lakshmi and Vishnu (known as Lakshmi-Narayana when shown together) are captured in an intimate embrace; the portrayal is unusual because they are both the same height, standing as equals. Another notable artwork is a watercolor decorated with silver and gold that demonstrates Lakshmi’s humility while she lovingly massages Vishnu’s feet.

The second and largest section of the exhibition focuses on objects that show Vishnu in the forms of his avatars, earthly and sometimes mortal beings who bring peace to humankind. The avatars include not only his human forms, Krishna and Rama, but also animals ranging from a fish to a ferocious lion. Among the artworks representing the animal avatars are an illustrated page from the Dashavatara, or Ten Avatar, series that features Varaha, the boar, saving the earth by raising it out of the sea, and a bronze of the man-lion avatar Yoga-Narasimha created in the twelfth century. Krishna is the most revered of Vishnu’s avatars and appears in many legends that reveal his complex personality, ranging from young prankster to divine ruler. One of the highlighted depictions of Krishna is an exquisitely decorated page from a Dashavatara series that depicts Krishna as a young man playing a flute for a group of milkmaids. Vishnu’s multifaceted character is embraced by his followers (known as Vaishnavas), some of whom choose to worship a specific avatar rather than the god’s primary form.

Vishnu has been worshipped for more than two millennia by people of diverse backgrounds and tastes. The final section of the exhibition will focus on the ritual objects used for prayer as well as images of Vaishnavas in prayer. Although most devotees of Vishnu visit public temples, much daily worship takes place at small shrines set up in homes. One intriguing object in this section is a gold shrine that was created in the form of a miniature throne. This intricately detailed shrine, no taller than six inches, has a tiny fringed parasol and is inlaid with rubies, emeralds, diamonds, and pearls. Also included in this selection are more-modern objects that demonstrate Vishnu’s enduring popularity, among them a twentieth-century papier-mâché pageant mask, a selection of early twentieth-century popular religious prints, and a pair of Bollywood posters.

Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior is organized by the Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, Tennessee, where it is on view February 19 through May 29, 2011. The exhibition is curated by Joan Cummins, Lisa and Bernard Selz Curator of Asian Art at the Brooklyn Museum, who also organized the Brooklyn Museum presentation. This exhibition is made possible in part by the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation and an anonymous donor. Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with an introductory essay and object entries by Dr. Cummins and scholarly essays by Leslie C. Orr, Concordia University; Cynthia Packert, Middlebury College; and Doris Meth Srinivasan, SUNY Stony Brook.

Press Area of Website

View Original