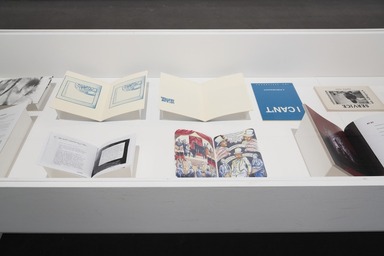

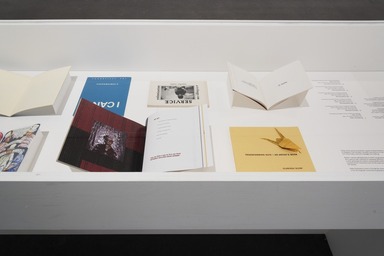

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_01_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_02_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_03_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_04_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_05_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_06_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_07_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_08_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_09_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_10_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_11_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_12_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_13_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_14_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_15_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_16_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_17_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_18_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_19_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_20_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_21_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_22_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_23_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_24_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_25_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_26_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_27_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_28_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_29_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_30_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_31_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_32_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_33_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_34_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_35_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_36_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_37_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_38_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_39_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_40_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_41_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_42_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_43_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_44_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_45_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_46_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_47_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_48_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_49_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_50_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, Thursday, August 23, 2018 through Sunday, March 31, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2018_Half_the_Picture_51_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2018)

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection

-

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection presents new acquisitions, rediscoveries, and major works from the Brooklyn Museum collection from an intersectional feminist perspective, reflecting on contemporary conversations about feminism and culture. Drawing its title from a 1989 Guerrilla Girls poster declaring “You’re seeing less than half the picture without the vision of women artists and artists of color,” the exhibition expands the definition of feminism beyond a movement to create equity between men and women. The more than fifty artists included here instead represent a plurality of voices advocating for their communities, their beliefs, and their hopes for equality across and between race, class, disability, and gender.

Half the Picture is organized by the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, now entering its second decade as the first, and still only, permanent museum space dedicated to feminist art. The exhibition highlights artists whose work commands our attention with direct messages of resistance and protest; questioning the historical narratives of the United States; calling for an understanding of how political realities are embedded in personal experience; exploring sexuality and exploitation in contexts of gendered power dynamics; and rethinking the biases present in art history and visual culture.

Works of art look different at different historical moments, and museums reflect the politics of both their time and history. Museums and their collections are not socially and culturally neutral. Traditionally, art history has operated from the premise that a work of art is static: the artist’s intention bestows a seemingly onetime meaning. Another approach considers that while meaning takes root when an artwork is made, new interpretations also form in the specific moment we look at the work, influenced by individual experience and cultural priorities.

Half the Picture proposes that works of art can have a dialogue across decades, whether by resonating with present-day concerns or shifting our understanding of an artist’s intention. This exhibition reflects current priorities and strategies for examining complex histories. The Brooklyn Museum endeavors to collect the work of a diverse array of artists, with varied backgrounds and approaches, sharing that work with our public and shepherding it into the future.

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection is organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator, and Carmen Hermo, Associate Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum. -

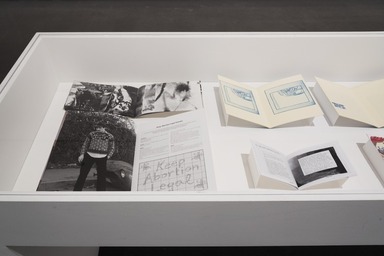

Resistance & Protest

In this section, art becomes an act of public protest against multiple forms of oppression by society or government, often in opposition to popular opinion. Artists may offer compelling narratives or pointed language to draw viewers to their cause, or employ conceptual gestures or abstraction to subtly shift perspectives.

Graphic art, performance, and other mediums meant to engage with a broader public carry an artist’s message far beyond the limited audience of a museum or gallery. Collectives such as the Artists' Poster Committee of Art Workers Coalition, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), and the Taller de Gráfica Popular used materials designed to allow images and text to be easily reproduced, ensuring that their political messages would be shared widely and efficiently. Adejoke Tugbiyele carried her Gélé Pride Flag in LGBTQ pride parades in both Nigeria and the United States, and Dread Scott performed On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide in downtown Brooklyn. In subtle, less-evident ways, works by Harmony Hammond, Sister Corita Kent, and Marilyn Minter call for mutual support among activists, more love, and breaking free from the constraints of conventional gender roles, barriers to political power, and isolation. -

Make America

Artists working in the United States have long grappled with the contradictions of a nation that was founded on the principle of “liberty and justice for all” but that often acted in opposition to that principle. The country was established by forced occupation and the removal of existing Native American societies, its power and wealth fed by the transatlantic slave trade and the exploitation of marginalized and disadvantaged communities.

The works in this section share a rejection of the white male supremacy central to U.S. history, from Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s exploration of American and Native American cultural priorities, to Yolanda Lopez’s commemoration of the Chicana women leaders of the farmworkers movement, to Catherine Green’s images of the thriving diaspora of Brooklyn’s West Indian Day Parade. Many of the works on view directly address the ways that violence has shaped the country, such as Nona Faustine’s call for recognizing the history of slavery in New York, Andy Warhol’s screenprint of police brutality against peaceful protesters during the Civil Rights Movement, and works by Vito Acconci and Pedro Reyes that provide a broader context for the nation’s current reckoning with gun violence. -

The Personal Is Political

The field of art history was revolutionized by feminists working in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and notably feminists of color, who set forth the notion that autobiography can form part of a wider social critique. The slogan “the personal is political” summarized how seemingly private matters usually considered the concern of individuals—such as health, family dynamics, disability, and sexuality—are inextricably linked to larger systemic oppressions and dominant social structures.

This resonance between the experiences of individuals and their broader societal implications is apparent in the works on view in this section. Artists like Käthe Kollwitz and LaToya Ruby Frazier speak across nearly a century, using black-and-white techniques to share the everyday challenges of living through war and in the face of environmental devastation, respectively. Beverly Buchanan and Graciela Iturbide refer to specific locations or regions—the American South and the Zapotec city of Juchitán, Mexico—to propose questions about commemoration, about who is honored and why. Works by Nayland Blake and Park McArthur create a literal shift in perspective, encouraging us to reconsider our own positions through the point of view of another person. -

Rewriting Art History

In 1971, feminist art historian Linda Nochlin asked, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” She answered the question in a groundbreaking essay that explored how women artists—and, by extension, artists from backgrounds marginalized by race, class, ability, and other intersecting oppressions—have been historically unable to access the mechanisms, support structures, and privilege of the academy and the art world at large. Nochlin and her peers, including Judy Chicago, whose monumental work The Dinner Party is installed in the nearby gallery, set the tone for a critical reevaluation of art history that continues today.

Artists have been at the forefront of these conversations, often from the vantage point of their own experiences. In this gallery, artworks by Dotty Attie, Miriam Schapiro, and Betty Tompkins ask us to reconsider the many contexts in which art is made, understood, and valued in terms of education, historical erasure, and biases that prize painting and sculpture over other mediums. Using a variety of approaches and techniques, Renee Cox, Lisa Reihana, and Stacy Lynn Waddell reimagine honorific portraiture, a genre rooted in whiteness, power, and privilege. Mickalene Thomas and Ghada Amer portray their subjects as models of self-possession and pleasure, challenging the long tradition of white male artists depicting nude women as available and passive. -

No Surprise

Recent public reckonings with sexual harassment and assault in the cultural sphere have underscored entrenched sexism and gender-based violence, bringing needed attention to their prevalence. As movements like #MeToo, #NotSurprised, and #TimesUp illuminate persistent abuses of power, artists uncover exploitation in both the private and public spheres, move beyond the binary genders of male and female—and the limiting roles they impose on individuals—and reframe our understanding of how consent, power, and gender intersect.

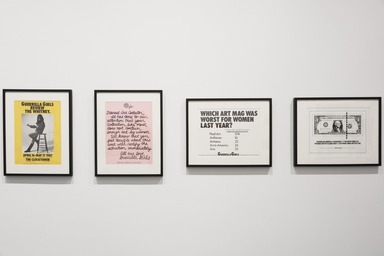

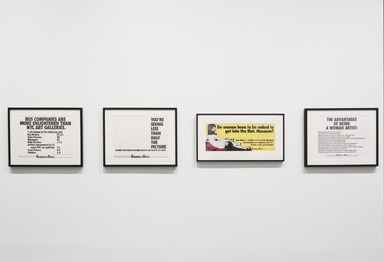

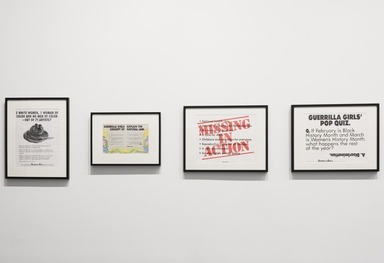

In works made in the 1970s and 1980s, long before the current waves of feminist activism, artists such as Ida Applebroog, Laurie Simmons, and Martha Rosler challenged the idealization of the family and home by depicting the menacing violence that sometimes takes place there. The Guerrilla Girls fused activism and art, bringing their messages of gender equity in the arts, health care, and the workplace to the streets of New York. More recently, Zanele Muholi enlists photography as “visual activism,” documenting her vibrant LGBTQ and gender-nonconforming community in South Africa. Sue Coe’s 1992 print of Anita Hill depicts the ways that women are put on trial for speaking out against workplace sexual harassment, while Betty Tompkins’s 2018 Apologia brings the weight of art history to bear on the formulaic apologies of powerful men. -

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection presents new acquisitions, rediscoveries, and major works from the Brooklyn Museum collection from an intersectional feminist perspective, reflecting on contemporary conversations about feminism and culture. Drawing its title from a 1989 Guerrilla Girls poster declaring “You’re seeing less than half the picture without the vision of women artists and artists of color,” the exhibition expands the definition of feminism beyond a movement to create equity between men and women. The more than fifty artists included here instead represent a plurality of voices advocating for their communities, their beliefs, and their hopes for equality across and between race, class, disability, and gender.

Half the Picture is organized by the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, now entering its second decade as the first, and still only, permanent museum space dedicated to feminist art. The exhibition highlights artists whose work commands our attention with direct messages of resistance and protest; questioning the historical narratives of the United States; calling for an understanding of how political realities are embedded in personal experience; exploring sexuality and exploitation in contexts of gendered power dynamics; and rethinking the biases present in art history and visual culture.

Works of art look different at different historical moments, and museums reflect the politics of both their time and history. Museums and their collections are not socially and culturally neutral. Traditionally, art history has operated from the premise that a work of art is static: the artist’s intention bestows a seemingly onetime meaning. Another approach considers that while meaning takes root when an artwork is made, new interpretations also form in the specific moment we look at the work, influenced by individual experience and cultural priorities.

Half the Picture proposes that works of art can have a dialogue across decades, whether by resonating with present-day concerns or shifting our understanding of an artist’s intention. This exhibition reflects current priorities and strategies for examining complex histories. The Brooklyn Museum endeavors to collect the work of a diverse array of artists, with varied backgrounds and approaches, sharing that work with our public and shepherding it into the future.

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection is organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator, and Carmen Hermo, Associate Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum. -

Resistance & Protest

In this section, art becomes an act of public protest against multiple forms of oppression by society or government, often in opposition to popular opinion. Artists may offer compelling narratives or pointed language to draw viewers to their cause, or employ conceptual gestures or abstraction to subtly shift perspectives.

Graphic art, performance, and other mediums meant to engage with a broader public carry an artist’s message far beyond the limited audience of a museum or gallery. Collectives such as the Artists' Poster Committee of Art Workers Coalition, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), and the Taller de Gráfica Popular used materials designed to allow images and text to be easily reproduced, ensuring that their political messages would be shared widely and efficiently. Adejoke Tugbiyele carried her Gélé Pride Flag in LGBTQ pride parades in both Nigeria and the United States, and Dread Scott performed On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide in downtown Brooklyn. In subtle, less-evident ways, works by Harmony Hammond, Sister Corita Kent, and Marilyn Minter call for mutual support among activists, more love, and breaking free from the constraints of conventional gender roles, barriers to political power, and isolation. -

Make America

Artists working in the United States have long grappled with the contradictions of a nation that was founded on the principle of “liberty and justice for all” but that often acted in opposition to that principle. The country was established by forced occupation and the removal of existing Native American societies, its power and wealth fed by the transatlantic slave trade and the exploitation of marginalized and disadvantaged communities.

The works in this section share a rejection of the white male supremacy central to U.S. history, from Jaune Quick-to-See Smith’s exploration of American and Native American cultural priorities, to Yolanda Lopez’s commemoration of the Chicana women leaders of the farmworkers movement, to Catherine Green’s images of the thriving diaspora of Brooklyn’s West Indian Day Parade. Many of the works on view directly address the ways that violence has shaped the country, such as Nona Faustine’s call for recognizing the history of slavery in New York, Andy Warhol’s screenprint of police brutality against peaceful protesters during the Civil Rights Movement, and works by Vito Acconci and Pedro Reyes that provide a broader context for the nation’s current reckoning with gun violence. -

The Personal Is Political

The field of art history was revolutionized by feminists working in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and notably feminists of color, who set forth the notion that autobiography can form part of a wider social critique. The slogan “the personal is political” summarized how seemingly private matters usually considered the concern of individuals—such as health, family dynamics, disability, and sexuality—are inextricably linked to larger systemic oppressions and dominant social structures.

This resonance between the experiences of individuals and their broader societal implications is apparent in the works on view in this section. Artists like Käthe Kollwitz and LaToya Ruby Frazier speak across nearly a century, using black-and-white techniques to share the everyday challenges of living through war and in the face of environmental devastation, respectively. Beverly Buchanan and Graciela Iturbide refer to specific locations or regions—the American South and the Zapotec city of Juchitán, Mexico—to propose questions about commemoration, about who is honored and why. Works by Nayland Blake and Park McArthur create a literal shift in perspective, encouraging us to reconsider our own positions through the point of view of another person. -

Rewriting Art History

In 1971, feminist art historian Linda Nochlin asked, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” She answered the question in a groundbreaking essay that explored how women artists—and, by extension, artists from backgrounds marginalized by race, class, ability, and other intersecting oppressions—have been historically unable to access the mechanisms, support structures, and privilege of the academy and the art world at large. Nochlin and her peers, including Judy Chicago, whose monumental work The Dinner Party is installed in the nearby gallery, set the tone for a critical reevaluation of art history that continues today.

Artists have been at the forefront of these conversations, often from the vantage point of their own experiences. In this gallery, artworks by Dotty Attie, Miriam Schapiro, and Betty Tompkins ask us to reconsider the many contexts in which art is made, understood, and valued in terms of education, historical erasure, and biases that prize painting and sculpture over other mediums. Using a variety of approaches and techniques, Renee Cox, Lisa Reihana, and Stacy Lynn Waddell reimagine honorific portraiture, a genre rooted in whiteness, power, and privilege. Mickalene Thomas and Ghada Amer portray their subjects as models of self-possession and pleasure, challenging the long tradition of white male artists depicting nude women as available and passive. -

No Surprise

Recent public reckonings with sexual harassment and assault in the cultural sphere have underscored entrenched sexism and gender-based violence, bringing needed attention to their prevalence. As movements like #MeToo, #NotSurprised, and #TimesUp illuminate persistent abuses of power, artists uncover exploitation in both the private and public spheres, move beyond the binary genders of male and female—and the limiting roles they impose on individuals—and reframe our understanding of how consent, power, and gender intersect.

In works made in the 1970s and 1980s, long before the current waves of feminist activism, artists such as Ida Applebroog, Laurie Simmons, and Martha Rosler challenged the idealization of the family and home by depicting the menacing violence that sometimes takes place there. The Guerrilla Girls fused activism and art, bringing their messages of gender equity in the arts, health care, and the workplace to the streets of New York. More recently, Zanele Muholi enlists photography as “visual activism,” documenting her vibrant LGBTQ and gender-nonconforming community in South Africa. Sue Coe’s 1992 print of Anita Hill depicts the ways that women are put on trial for speaking out against workplace sexual harassment, while Betty Tompkins’s 2018 Apologia brings the weight of art history to bear on the formulaic apologies of powerful men.

-

July 5, 2018

The Brooklyn Museum is pleased to announce Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, an exhibition presenting major works, new acquisitions, and rediscoveries in the Museum’s collection through an intersectional feminist lens. Highlighting work created in response to crucial social and political moments from the last one hundred years, from World War I to the Civil Rights Movement and #MeToo, the exhibition foregrounds more than fifty artists who use their work to advocate for their communities, their beliefs, and their hopes for equality across race, class, and gender. The exhibition is organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator, and Carmen Hermo, Assistant Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, and is on view August 31, 2018, through March 31, 2019.

Half the Picture draws its title from a 1989 Guerrilla Girls poster that declares, “You’re seeing less than half the picture without the vision of women artists and artists of color.” “The power of the Guerrilla Girls lies in their funny, concise, and biting graphic work, made to rally support and inspire action on behalf of a cause; to combat stereotypes and dominant narratives,” explains Morris. “Presenting the equally compelling work of over fifty other artists, Half the Picture explores how artists get the rest of us to pay attention.”

A number of recent acquisitions will be on view for the first time, including two works from Beverly Buchanan’s best-known series of shack sculptures; Betty Tompkins’s Fuck Painting #6 (1973), marking the first time a work from this controversial series is on view in an American museum; and Nona Faustine’s Isabelle, Lefferts House, Brooklyn (2016), in which the artist positions herself in front of the Lefferts homestead, a historic colonial farmhouse built by a family of slaveholders, which still stands in Prospect Park.

Other highlights include Renee Cox’s monumental photograph Yo Mama (1993); Dara Birnbaum’s iconic video Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978/79); and Wendy Red Star’s 1880 Crow Peace Delegation series, which features historical photographs overlaid with annotations drawing attention to the stereotypes and appropriation of Native Americans by mainstream popular culture. Also on view is Harmony Hammond’s large-scale sculpture Hunkertime (1979–80), in which a number of heavily wrapped ladder-like forms are displayed in close arrangement, evoking a supportive sisterhood. The earliest works in the show, dating from the 1920s, are a group of woodcuts by German artist Käthe Kollwitz, which depict the lives of women and the less fortunate in the gruesome aftermath of World War I.

Other notable artists included are Vito Acconci, Sue Coe, An-My Lê, Yolanda López, Park McArthur, Zanele Muholi, Dread Scott, Joan Semmel, Lorna Simpson, Kiki Smith, Nancy Spero, Mickalene Thomas, Adejoke Tugbiyele, and Taller de Gráfica Popular, among many others.

“The exhibition focuses on work that feels both meaningful and relevant in relationship to current politics and conversations about feminism, by artists of varied backgrounds, approaches, and intersecting identities,” adds Hermo.

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection is organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator, and Carmen Hermo, Assistant Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art.

Press Area of Website

View Original -

August 24, 2018

The Brooklyn Museum is pleased to announce Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection, an exhibition presenting major works, new acquisitions, and rediscoveries in the Museum’s collection through an intersectional feminist lens. Highlighting work created in response to crucial social and political moments from the last one hundred years, from World War I to the Civil Rights Movement and #MeToo, the exhibition foregrounds more than fifty artists who use their work to advocate for their communities, their beliefs, and their hopes for equality across race, class, and gender. The exhibition is organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator, and Carmen Hermo, Assistant Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, and is on view August 23, 2018, through March 31, 2019.

Half the Picture draws its title from a 1989 Guerrilla Girls poster that declares, “You’re seeing less than half the picture without the vision of women artists and artists of color.” “The power of the Guerrilla Girls lies in their funny, concise, and biting graphic work, made to rally support and inspire action on behalf of a cause; to combat stereotypes and dominant narratives,” explains Morris. “Presenting the equally compelling work of over fifty other artists, Half the Picture explores how artists get the rest of us to pay attention.”

A number of recent acquisitions will be on view for the first time, including two works from Beverly Buchanan’s best-known series of shack sculptures; Betty Tompkins’s Fuck Painting #6 (1973), marking the first time a work from this controversial series is on view in an American museum; and Nona Faustine’s Isabelle, Lefferts House, Brooklyn (2016), in which the artist positions herself in front of the Lefferts homestead, a historic colonial farmhouse built by a family of slaveholders, which still stands in Prospect Park.

Other highlights include Renee Cox’s monumental photograph Yo Mama (1993); Dara Birnbaum’s iconic video Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978/79); and Wendy Red Star’s 1880 Crow Peace Delegation series, which features historical photographs overlaid with annotations drawing attention to the stereotypes and appropriation of Native Americans by mainstream popular culture. Also on view is Harmony Hammond’s large-scale sculpture Hunkertime (1979–80), in which a number of heavily wrapped ladder-like forms are displayed in close arrangement, evoking a supportive sisterhood. The earliest works in the show, dating from the 1920s, are a group of woodcuts by German artist Käthe Kollwitz, which depict the lives of women and the less fortunate in the gruesome aftermath of World War I.

Other notable artists included are Vito Acconci, Sue Coe, An-My Lê, Yolanda López, Park McArthur, Zanele Muholi, Dread Scott, Joan Semmel, Lorna Simpson, Kiki Smith, Nancy Spero, Mickalene Thomas, Adejoke Tugbiyele, and Taller de Gráfica Popular, among many others.

“The exhibition focuses on work that feels both meaningful and relevant in relationship to current politics and conversations about feminism, by artists of varied backgrounds, approaches, and intersecting identities,” adds Hermo.

Half the Picture: A Feminist Look at the Collection is organized by Catherine Morris, Sackler Senior Curator, and Carmen Hermo, Assistant Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art.

Press Area of Website

View Original