One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_01_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_02_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_03_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_04_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_05_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_06_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_07_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_08_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_09_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_10_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_11_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_12_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_13_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_14_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_15_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_16_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_17_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_18_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_19_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_20_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

One: Egúngún, Friday, February 08, 2019 through Sunday, August 18, 2019 (Image: DIG_E_2019_One_Egungun_21_PS11.jpg Brooklyn Museum. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado) photograph, 2019)

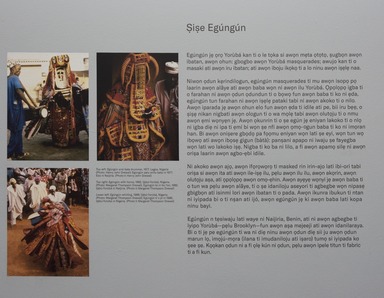

One: Egúngún

-

Special Features of a Paka Egúngún

Yorùbá egúngún masquerades vary regionally across southwestern Nigeria, with different kinds of egúngún playing distinct roles. Accordingly, masks are classified generally as egúngún, and then divided into specific types. Some masks also have given names, like a person. What’s true for one egúngún is not always true for all.

Specifically a paka egúngún, the mask now in Brooklyn was made in the city of Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́ between 1920 and 1948. Found only in the Ọyọ State region, paka dazzles the eye with colorful fabric panels that swirl into motion during intricate dances. Unlike other egúngún, it does not have a wooden or gourd headpiece. Composed of hundreds of layered textiles from Africa, Europe, and Asia, the costume reflects its owner’s wealth and prestige, while providing a physical place for ancestral spirits to inhabit. One of many egúngún used in Ọyọ State, paka takes on roles ranging from the glamorous escort of other egúngún masks representing elder ancestors, to the wild janduku (“hooligan”), who chases after spectators.

The many textiles on a paka egúngún invoke ideals of success, power, and influence in a larger-than-life format. Most of the fabric on the egúngún is from garments that have been cut and re-sewn into strip-like panels. These panels amplify the masker’s performance by swaying with each movement. They also visually reference a verse from the literary corpus of Ifá, the Yorùbá religious and divinatory system: “cloth only wears to shreds.” Just as cloth wears to shreds, the living are transformed via death into a state of immortality. Neither disappears, but exists in a new, enduring form. In the egúngún, cloths blur together when in motion, becoming more than their individual parts. They become a bridge that unites a lineage across time and space. -

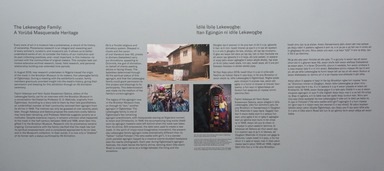

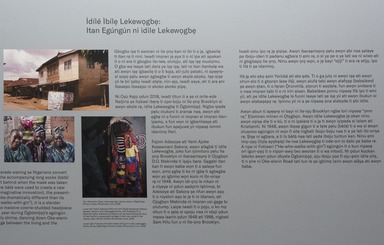

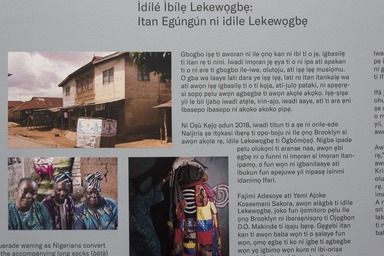

The Lekewọgbẹ Family: A Yorùbá Masquerade Heritage

In August 2018, new research undertaken in Nigeria traced the origin of the mask in the Brooklyn Museum to its makers, the Lekewọgbẹ family of Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́. During a meeting with the exhibition’s curator, family members graciously provided insight into the mask’s history, giving their permission and blessing for this exhibition through an Ifá divination ceremony.

Fajimi Adesoye and Yemi Ajoke Koseemani Sakora, elders of the Lekewọgbẹ family, sat for an interview with the Brooklyn Museum in a conversation facilitated by Professor D. O. Makinde, originally from Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́. According to a story told to them by their late grandfathers, an unidentified member of their community removed their egúngún from its shrine in 1948. The motives can only be guessed at over seventy years later, though Adesoye and Sakora propose the costume’s costly fabrics may have been tempting, and Professor Makinde suggests poverty as a motivator. Despite extensive inquiry, it remains unknown what happened to the mask in the half-century between 1948 and 1998, when Sam Hilu gifted it to the Brooklyn Museum. Research into its provenance remains ongoing. Conversations with the family clarified that the mask has lost its spiritual empowerment, and is considered appropriate to be on view and in the Museum’s collection. In their words, it is now only a “shadow” of its former self, a status confirmed by Ifá divination.

Ifá is a Yorúbà religious and divinatory system. Steeped in rituals and the canon of oral literature (ese ifá), priests or diviners (babaláwo) carry out divinations, appealing to Ọ̀rúnmìlà, the god of divination, on behalf of clients seeking advice or facing illness. The babaláwo determined through Ifá the spiritual status of this egúngún, and that the Lekewọgbẹ family could grant permission to this project and blessings to its participants. This determination was made via the medium of the family’s current egúngún.

The legacy of the egúngún now in the Brooklyn Museum lives on through its “son,” another egúngún in Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́. The Lekewọgbẹ family is one of Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́’s few remaining egúngún practitioners, with masquerade waning as Nigerians convert to Islam and Christianity. In 1948, the accompanying long socks (bàtà) worn by egúngún maskers were left behind when the mask was taken from its shrine. Still empowered, the bàtà were used to create a new mask. In the spirit of ìmọjú-mọra (imaginative innovation) the present-day Lekewọgbẹ family egúngún looks dramatically different than its “father.” Called Fotinroin (“He-who-walks-with-gin”), it is a slender cloth-paneled egúngún topped by a massive cowrie-studded headpiece (see the nearby photograph). Each year during Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́’s egúngún festivals, the mask leaves the family shrine, dancing down Oke-elerin Road to once again serve as a bridge between the living and the ancestors. -

One: Egúngún

One: Egúngún tells the life story of an early twentieth-century Yorùbá masquerade dance costume (egúngún), from its origins in Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́, Nigeria, to its current home in Brooklyn. The Yorùbá egúngún masquerade and masking society honors ancestors and connects them with their living descendants. Centuries old, egúngún is still practiced in parts of Nigeria, the Republic of Benin, and in areas of the Yorùbá diaspora.

While previously exhibited at the Brooklyn Museum, this egúngún has not been the focus of extensive research until now. By searching out the history of a single egúngún, this exhibition emphasizes the global connections of African masquerades, and it challenges static misconceptions of “tradition,” which wrongly propose that cultural practices don’t change over time. It also celebrates the unique story of this particular costume, looking at it as an individual creation within a larger cultural practice. Though no longer ritually empowered according to its community of origin, the egúngún at the Brooklyn Museum remains a compelling symbol of belief, history, and global connections.

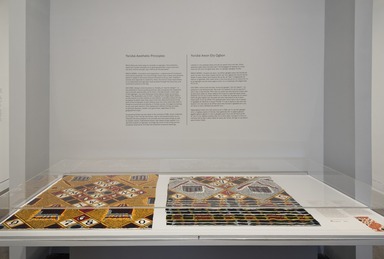

The exhibition also features four distinctive West African textiles and garments: aṣọ-òkè (strip-woven cloth), àdìrẹ (resist-dye), agbádá (embroidered prestige tunic), and ankara (“wax print”). Representing just a few of the many fabrics and disassembled garments that compose this egúngún, these related works further demonstrate the role of cloth in Yorùbá belief and aesthetics.

In addition, filmed interviews with Nigerian artists, scholars, and masquerade practitioners present multiple views of the historical and contemporary significance of egúngún on the continent, while a text contributed by a member of the Brooklyn Yorùbá community adds a diasporic perspective.

At the request of the Lekewọgbẹ family—the makers of this egúngún—this exhibition honors their family name and masquerade heritage. We thank and acknowledge them.

One: Egúngún is curated by Kristen Windmuller-Luna, Sills Family Consulting Curator, African Arts, Brooklyn Museum. -

Yoruba Aesthetic Principles

While there are many ways to consider an egúngún, this exhibition takes two Yorùbá concepts as its guiding premises: ìmọjú-mọra and ojú-ọnà. A third concept, àṣẹ, informs all Yorùbá belief.

Ìmọjú-mọra—innovation and imagination—underscores all Yorùbá art and cultural practices. It is only through ìmọjú-mọra, a keen and sensitive ability to adapt to the times without direction to do so, that “tradition” evolves and responds to modernity. Here, the lens of ìmọjú-mọra allows us to appreciate how egúngún have evolved through the centuries, and continue to evolve to this day.

Ojú-ọnà—design consciousness or, literally, an “eye for design”—is the exhibition’s second guiding premise. Ojú-ọnà guides the respectful and culturally appropriate use of cloth in Yorùbá culture. In the case of this egúngún, ojú-ọnà influences which fabrics make up its many layers. The expressive use of cloth—ranging from indigo-dyed cottons on the interior to shiny velvets on the exterior—provides a place for the ancestors to dwell when they return from the otherworld (ọ̀rún) to the land of the living (ayé). It also reflects upon the many ways that cloth is linked to community and identity in Yorùbá society. Arranged according to ojú-ọnà, each textile in this masterwork reflects Yorùbá concepts of spiritual devotion, wealth, and good taste, regardless of their geographic origin.

Empowering these two key ideas is the concept of àṣẹ, which underlies all things in the Yorùbá worldview. Àṣẹ is conceived broadly as an effective life force present in all animate and inanimate things as well as spoken words. A generative power, àṣẹ makes things happen: it is àṣẹ that enables an egúngún to bridge the world of the living and the ancestral otherworld, and àṣẹ that amplifies ancestral blessings. -

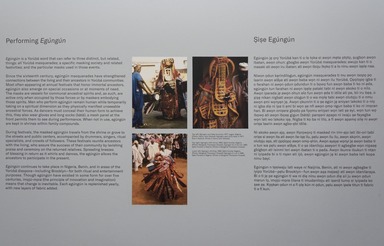

Performing Egúngún

Egúngún is a Yorùbá word that can refer to three distinct, but related, things: all Yorùbá masquerades; a specific masking society and related festivities; and the particular masks used in those events.

Since the sixteenth century, egúngún masquerades have strengthened connections between the living and their ancestors in Yorùbá communities. Most often appearing at annual festivals that honor immortal ancestors, egúngún also emerge on special occasions or at moments of need. The masks are vessels for communal ancestral spirits and, as such, are active only when occupied by those forces or by maskers embodying those spirits. Men who perform egúngún remain human while temporarily taking on a spiritual dimension as they physically manifest unseeable ancestral forces. As dancers must conceal their human form to achieve this, they also wear gloves and long socks (bàtà); a mesh panel at the front permits them to see during performance. When not in use, egúngún are kept in shrines within family compounds.

During festivals, the masked egúngún travels from the shrine or grove to the streets and public centers, accompanied by drummers, singers, ritual specialists, and crowds of followers. These festivals reunite ancestors with the living, who assure the success of their community by lavishing praise and ceremony on the returned relatives. Spreading breezes of blessing in return as it whirls and dances, the egúngún allows the ancestors to participate in the present.

Egúngún continues to take place in Nigeria, Benin, and in areas of the Yorùbá diaspora—including Brooklyn—for both ritual and entertainment purposes. Though egúngún have existed in some form for over five centuries, ìmọjú-mọra (the principle of innovation and imagination) means that change is inevitable. Each egúngún is replenished yearly, with new layers of fabric added. -

The Meanings of Cloth

Cloth—like the ancestors—is immortal in Yorùbá belief. When ancestors return to the world of the living, they arrive as a cloth-covered egúngún, as described in the adage “pátápátá leégun ńfaṣọ borí” (“the egúngún [eégun] completely covers his head with a shroud).” Cloth (aṣọ) ties the egúngún spirit to the human world, making the ancestral otherworld visible. Simultaneously, it conceals the human body of the dancer inside the costume. Finally, it enhances a mask owner’s prestige by showcasing wealth and design sense (ojú-ọnà). Like all paka egúngún, this mask is made from velvets, damasks, cottons, silks, and embroideries. Looking closely at these textiles tells us more about the life of the costume, and how fabric communicates social values and religious beliefs.

Yorùbá culture esteems wearing the right cloth for the right occasion, and that is no different for egúngún masquerades. Primarily sourced from prestige garments, the fabrics in this mask have been cut and sewn into symmetrically arranged panels. Ladder-like compositions of triangular and rectangular pieces of imported fabrics form the shimmering exterior panels. The triangular fabric shapes on the mask’s central tiers evoke similarly shaped protective amulets and drums that accompany egúngún performers. Reds dominate for their association with Ṣàngó, historic king of Ọ̀yọ́, where egúngún is said to have begun. Triangular trim surrounding panels allude to ancestral blessings: gbala, the name of this trim, evokes Yorùbá words for “saving” or “rescuing.”

The costume must conform to Yorùbá aesthetics while permitting easy movement. For paka egúngún, whose actions range from solemn walking to running to spinning, the costume’s loose, shroud-like inner layer is made of durable, locally made kíjìpá and aṣọ-òkè fabrics. In contrast, rare and delicate imported fabrics appear on the exterior, where they can be easily admired. Fabrics in this egúngún have been traced to Nigeria, England, and India.

-

December 19, 2018

A single egúngún masquerade costume, on view from February 8 to August 18, 2019, traces the rich history of Nigeria’s Yorùbá culture from West Africa to the United States.

One: Egúngún, which features a single Yorùbá masquerade costume from the Brooklyn Museum’s collection, uses new research and multiple perspectives to emphasize the global connections and contemporary contexts of African masquerades. Made during the early twentieth century in southwestern Nigeria, this costume—or egúngún—is composed of more than three hundred different textiles from Africa, Europe, and Asia, suspended from a single length of wood, which swirl in motion during festival dances honoring departed ancestors. The presentation is accompanied by photographs and footage of Yorùbá masquerade festivals, related textiles, and new curatorial research that uncovers the vibrant history of this particular egúngún, tracing its journey from West Africa to Brooklyn.

The exhibition is curated by Kristen Windmuller-Luna, Sills Family Consulting Curator, African Arts, Brooklyn Museum. It is part of the One Brooklyn series, in which each exhibition focuses on an individual work from the Brooklyn Museum’s encyclopedic collection, revealing the many stories woven into a single work of art.

One: Egúngún tells the life story of a singular early twentieth-century Yorùbá masquerade costume from its origins in Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́, in southwestern Nigeria, to its current home in Brooklyn. A paka type of egúngún, the masquerade costume is defined by its numerous suspended fabric panels. Composed of materials ranging from indigo-dyed cottons on the interior to imported fabrics on the outside, the egúngún is meant to provide a place for the ancestors to dwell, and it reflects the many ways that cloth is linked to community, identity, and honor in Yorùbá society. Each textile in the costume indicates the spiritual devotion, wealth, and good taste of the family that created it. Though no longer ritually empowered or used in religious practices, the egúngún at the Brooklyn Museum remains a powerful symbol of belief, history, and global connections.

Included in the exhibition is new research and filming done throughout Nigeria in summer 2018 by Windmuller-Luna, thanks to the support of the Sills Family Foundation. Her research traces the egúngún on view at the Museum back to its original makers, the Lekewọgbẹ family from the city of Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́. At their request, this exhibition will honor the Lekewọgbẹ name by telling the story of their family’s masquerade heritage in their own words, incorporating video filmed at their compound in August 2018. One: Egúngún includes text in both English and Yorùbá, marking the first time an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum has included wall labels in an African language. The exhibition will also feature a text contribution from Chief Ayanda Ifadara Ojeyimika Clarke, the Ajibilu Awo of Osogbo and a leader of the local Brooklyn Yorùbá community.

Since the sixteenth century, egúngún masquerades have been practiced in West Africa and its diasporas as a way to strengthen connections between living Yorùbá peoples and their ancestors. The masquerade practices vary from region to region in Nigeria, with each egúngún playing a specific role in these performances. The egúngún in the Brooklyn Museum’s collection represents an important cultural practice that has evolved and expanded over five centuries, and is still performed in Nigeria, Benin, and in areas of the diaspora—including Brooklyn—for both ritual and entertainment purposes.

“It’s key to consider an egúngún—or any piece of art from Africa or around the world—from multiple angles and with multiple sources, from oral history to written documents to fiber analysis,” says Windmuller-Luna. “I hope that with this exhibition we are able to introduce many voices and perspectives into our galleries, celebrating how egúngún is both part of Yorùbá history and a vibrant part of its present, whether in Nigeria or here in Brooklyn.”

Also on view are four distinctive West African textiles and garments that demonstrate the importance of cloth in Yorùbá belief and aesthetics. These selected textiles—which include aṣọ-òkè (strip-woven cloth), àdìrẹ (resist -dye), agbádá (embroidered prestige tunic), and ankara (wax print)—represent just a few of the many textiles that compose this egúngún, whose fabric components underwent detailed historical and scientific examinations in preparation for the exhibition. When combined with the oral history of the masquerade costume, this information helps to date the work more precisely. By focusing on a single egúngún, this exhibition emphasizes the global connections of African masquerades, while also celebrating the unique life history of this particular costume.

One Brooklyn is made possible by a generous contribution from JPMorgan Chase & Co. Additional support for One: Egúngún is provided by the Sills Family Foundation.

One: Egungun

View Original