How Do Conservators Handle Ancient Art?

Breaking down questions about the treatment and preservation of ancient artworks.

by Angela Leersnyder

January 10, 2025

Ask a Conservator

Ask a Conservator is a regular series demystifying the work that conservators do at the Brooklyn Museum.

The array of materials within the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive collection, from contemporary canvases to prehistoric sculptures, requires an equally broad range of conservation treatments. At any given time in the Conservation Lab, the Museum’s conservators are treating objects that could be up to 6,000 years apart in age. With that age difference comes a difference in approach. Let’s look at key questions that arise when we treat ancient art.

Ancient dirt vs. modern dirt: When to keep it

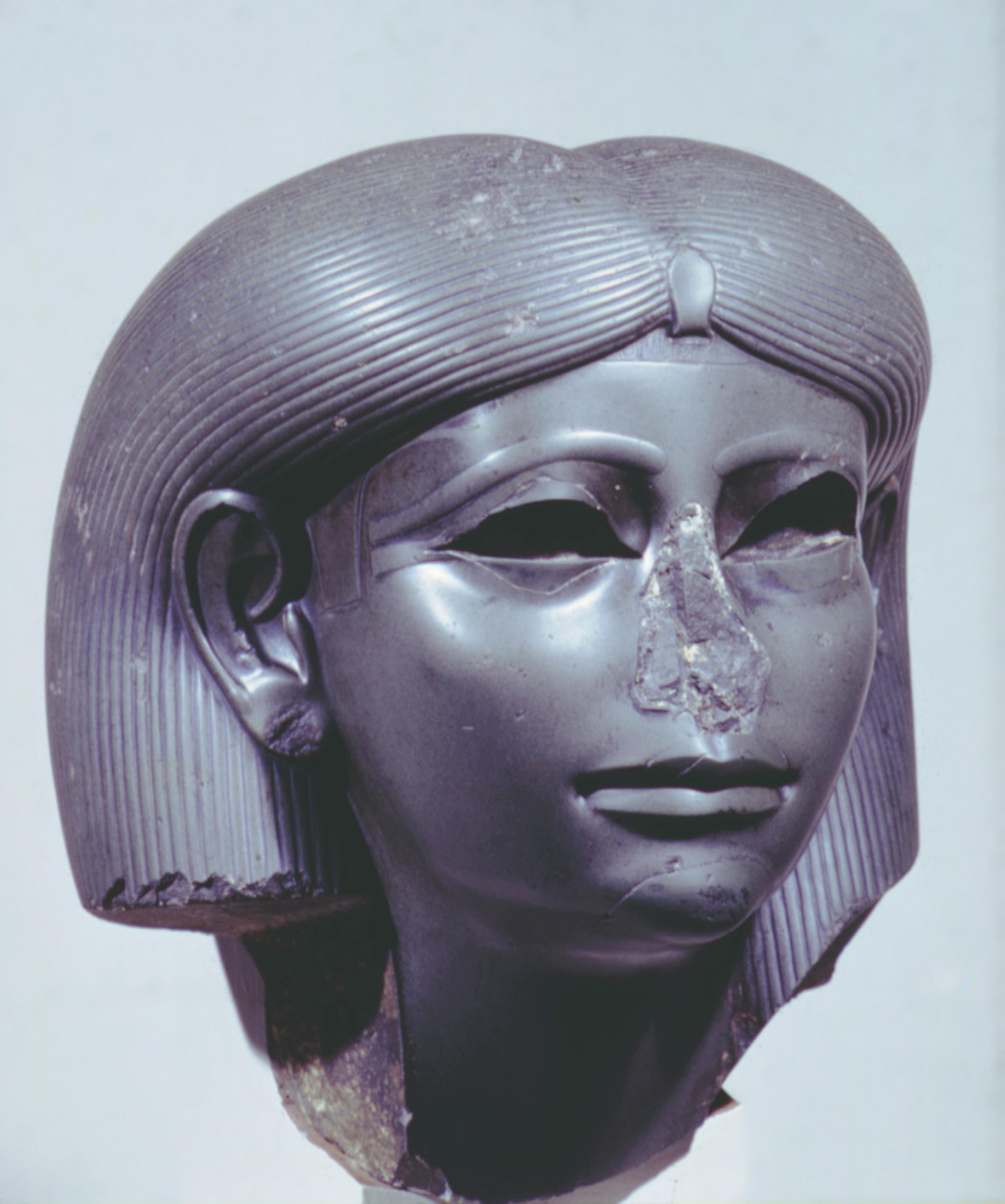

Cleaning is often the first step in the treatment process to ensure no dust or dirt is present and the object looks its best. However, for some ancient objects, the dirt is an integral part of their history and excavation context. Take Head from a Female Sphinx (ca. 1876–1842 B.C.E.), for example: the surface is clean overall, but if you look closer at the areas where pieces have broken off, there is dirt embedded in the stone.

Dirt is often removed from modern works, but here it is left in place to preserve this aspect of the sculpture’s past. While “newness” is an important factor for many newer objects, age holds significant value for ancient objects, so we approach surface dirt as a material to preserve rather than remove.

Repair or stabilize?

When an object is broken into fragments, it might make sense to put them back together. But what if you didn’t know what the piece originally looked like? Would you still try to reassemble it and make it look “new”? This question commonly arises in the conservation of ancient objects. Conservation teams often decide to repair the objects when possible, prioritizing their stability, but any purely aesthetic compensation added in must be supported by evidence from comparable objects and research.

For example, let’s compare Female Figure (ca. 3500–3400 B.C.E.) and Anthropoid Coffin of the Servant of the Great Palace, Teti (ca. 1339–1307 B.C.E.), two vastly different objects that both required some form of reassembly.

Female Figure was excavated in one piece; however, weaknesses in the clay from the lime content made it brittle, causing a hand to break off during travel in 2012. The break edges fit together almost perfectly, and the original alignment was well-documented in photographs, giving us a reliable guide. We reattached the hand to the figure with adhesive and applied small fills of plaster to further stabilize the break. Lastly, the plaster was painted to match the surrounding surface.

A different approach was required during a major conservation effort of Anthropoid Coffin of the Servant of the Great Palace, Teti. The coffin had many large losses in its surface. Before addressing them, the team categorized the fill areas, or the sections that needed repair, as structural, preventive, and/or aesthetic. Structural and preventive fills were completed to stabilize the object for the long term.

Aesthetic fills were deliberated carefully: Curators wanted to avoid creating a false sense of completeness. As there is no documentation of the coffin’s appearance before it was damaged, and its condition is a part of its journey as an object, it is not the conservator’s responsibility to try and make it look untouched. At the same time, we didn’t want the losses to be a visual distraction to visitors.

Ultimately only certain aesthetic areas were filled with plaster. Once the fills were completed, conservators either painted them to mimic the decoration of the surrounding area or applied a neutral color to blend into the surface.

To undo or to accept?

Conservation as an academic discipline is relatively new, having formed around the 1950s. However, people have been repairing artifacts for as long as they have been finding them. Ancient objects may have had historic repairs at some point after their creation, perhaps while they were in use or upon their excavation. Sometimes these repairs can be left in place, but in other instances, they need to be re-treated with a more appropriate conservation method or reversed for the object’s safety. This often entails a larger discussion with the curatorial team to consider the material used in the historic repair, the context in which it was applied, and how it is now interacting with the object.

For example, Head from a Female Sphinx contains plaster fills on the chin, lips, and both eyes. These repairs were reportedly completed in the 18th century, when Cardinal Alessandro Albani owned the head. The fills are stable, and though they are unmistakably a later addition, they are also now a part of the object’s history. Therefore, they have been left in place.

However, notice how other lost components have not been filled in, like the eyes. Filling those losses was not necessary for structural integrity, and the inlaid eyes’ removal is part of the sculpture’s journey, so no modern aesthetic fills have been added.

When historic repairs do endanger the object, we take action to mitigate the risk. At some point, two metal rods were inserted into the head so it could be displayed. The conservation team found that the rods were beginning to corrode, which could result in stress and damage to the sculpture. We carefully removed them and implemented a modern mounting system to protect the object while allowing it to be shown in the correct orientation.

While the approach to ancient art is different than that for more modern objects, the aim is always the same: to protect and stabilize the materials. Take a close look at our ancient collections and see if you can spot any other evidence of conservation!

Angela Leersnyder is the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Objects Conservation at the Brooklyn Museum.

More from this series

- Ask a Conservator

How Do You Handle Sensitive Materials?

By: Kate Wight TylerFrom building microclimates to considering cultural backgrounds, here are a few ways conservators work to protect artworks.

- Ask a Conservator

How Do You Become a Conservator?

By: Celeste MahoneyPeople from all types of backgrounds find themselves drawn to this unique career path.

- Ask a Conservator

What’s the Weirdest Work You’ve Ever Conserved?

By: Lisa BrunoIntroducing a new column that demystifies the work of museum conservators.