How Do Photographers Know When an Image is Complete?

Three artists from our exhibition In the Now address the final stages of their creative process.

by Corinne Segal

April 17, 2024

A new exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum brings together nearly 50 artists who are grappling with questions of power, identity, and history through photography. Titled In the Now: Gender and Nation in Europe, Selections from the Sir Mark Fehrs Haukohl Photography Collection, the exhibition shows photographs by women artists born or based in Europe. Much of their work addresses the continent’s intertwined legacies of colonialism, racism, and violence. The images also highlight the tension between an ever-changing geopolitical landscape and the medium of photography, which captures a single moment in time. With this in mind, we asked a few artists represented in the collection how they know when an image is complete.

In the Now: Gender and Nation in Europe, Selections from the Sir Mark Fehrs Haukohl Photography Collection is on view through July 7, 2024.

Milja Laurila

My writing professor said that he once “edited his novel to death,” and that can happen to images as well. How do you keep that sense of experiment, of spontaneity—of life!—in the final stage as well? I sometimes feel like my sketches are better than the finished works. Somehow, they seem to lose something on their way from first drafts to the gallery wall. Trying to make everything perfect can backfire.

Observatory was a long time in the making. I had small prints of it on my desk as early as 2009, and I created an initial exhibited version in 2015, but wasn’t satisfied with it. I felt I had a powerful work with these women. However, it didn’t feel right as prints on the wall; something was missing. So, I went back to the studio and experimented with different sizes, materials, and ways to arrange the women. I realized I wanted them to touch each other and the images to overlap, and when I made the first tests with a transparent material, I knew it was there; I could feel it in my body. Now the work will be complete.

In my work I don’t seek complete images.

Sarah Jones

The Rose Garden (Display: III/White) (I) (2007) is one of a group of ongoing works made in rose gardens in London’s public parks, gardens that are for everyone in the city. I make several visits to a location. Things often change. Sometimes the rose I’m thinking about photographing is kept well, sometimes unkempt.

Some flowerheads and leaves are newly formed, others are on the point of decay. Time is embedded in these transitions, fixed when I return to photograph with my large format camera. With these works I was interested in measuring, in using the camera to describe a familiar, everyday subject. You could think of these cultivated public spaces as pleasure gardens. Often with photography a flattening of space happens—the rose is pressed into a photographic realm, a bit like how a botanist might cut and preserve a plant in the field.

The lighting technique I use is called “night for day.” I photograph my subjects on location in broad daylight with studio lights. The park disappears, and the rose appears set into an inky dark space—a photographic night. Day and night collapse into one another. This rose is photographed from the back, i.e. it faces away from us into a fictional night.

After processing my film I make small-print proofs to think about the tone and scale of the work, with very slight adjustments, so all the roses across this series are in the same pictorial world. When I feel all these things fall into place, I then work closely on exhibition printing. All the plants are printed so that they approximate lifesize, so when you stand in front of the work, in the gallery, the experience approximates being in front of the rose itself. The work is done—to this stage, anyhow. The next is the framing: white so the image appears to float, and matte-sealed so you only see the subject and not yourself reflected.

Of course, the conversations around a work can mean a work is never completely done. A work can often change over time. My conversations with a viewer or collector, or a writer, gallerist or curator I may work with, can bring new things I hadn’t thought of, that often show ways to move forward—to make the next work.

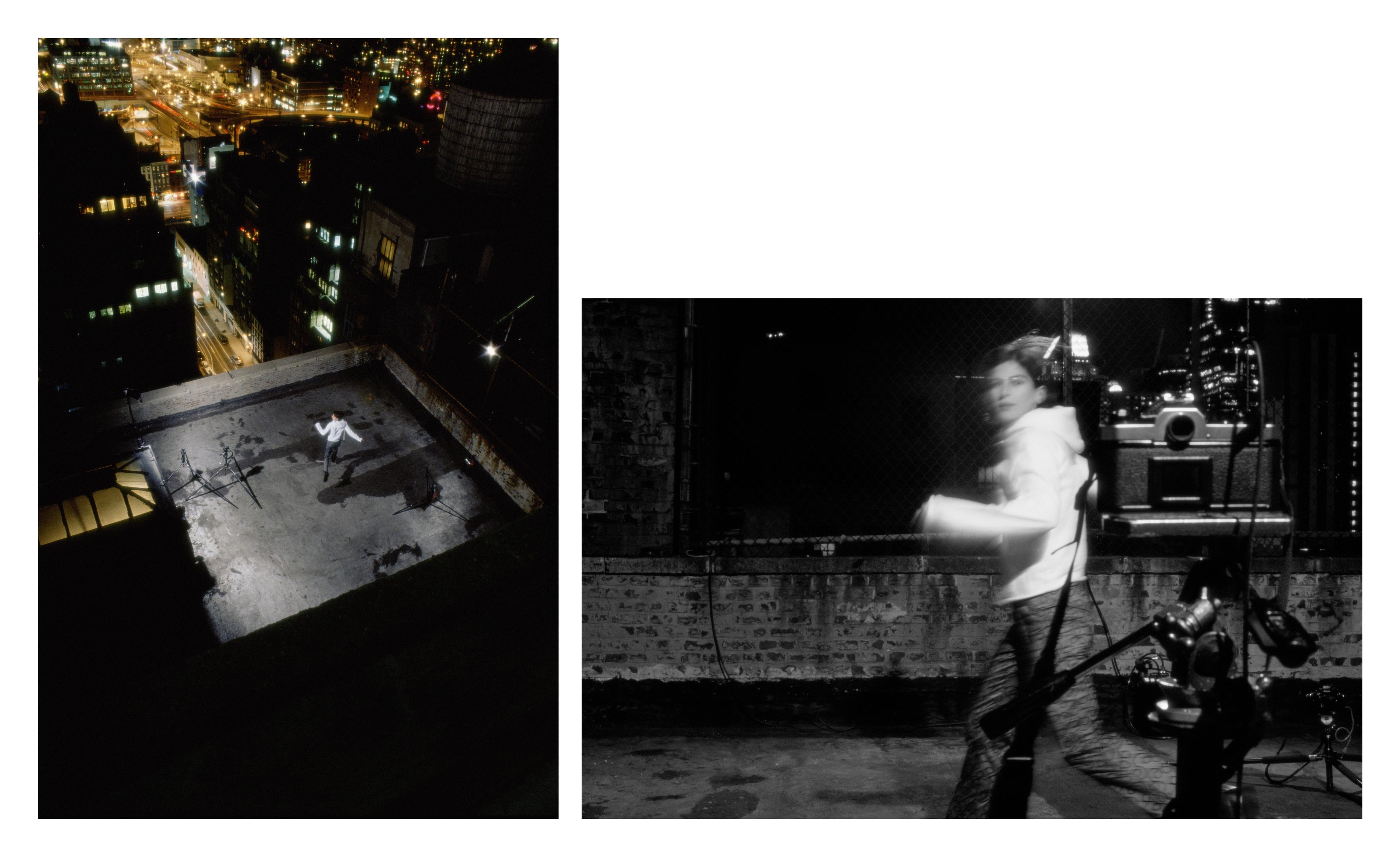

Barbara Probst

In my work I don’t seek complete images. On the contrary, I am specifically aiming for incomplete images without a complex narrative or subject matter, images that are somehow fragmentary and ambiguous as well as open and lightweight enough to easily connect to others of their kind. In other words, these images don’t make sense on their own. Only the viewer can bring them to life by seeing the group as a whole, looking at the relationships between the images, perhaps filling the gaps between them. I see the individual images of a group as cooperating agents dedicated to triggering a process in the mind of the viewer, wherever it might take them. When the images of a group collaborate successfully, when they are able to draw the viewer into such an adventure of looking, I would call the series complete.

Corinne Segal is Senior Digital Producer at the Brooklyn Museum.