Rembrandt to Picasso: Five Centuries of European Works on Paper

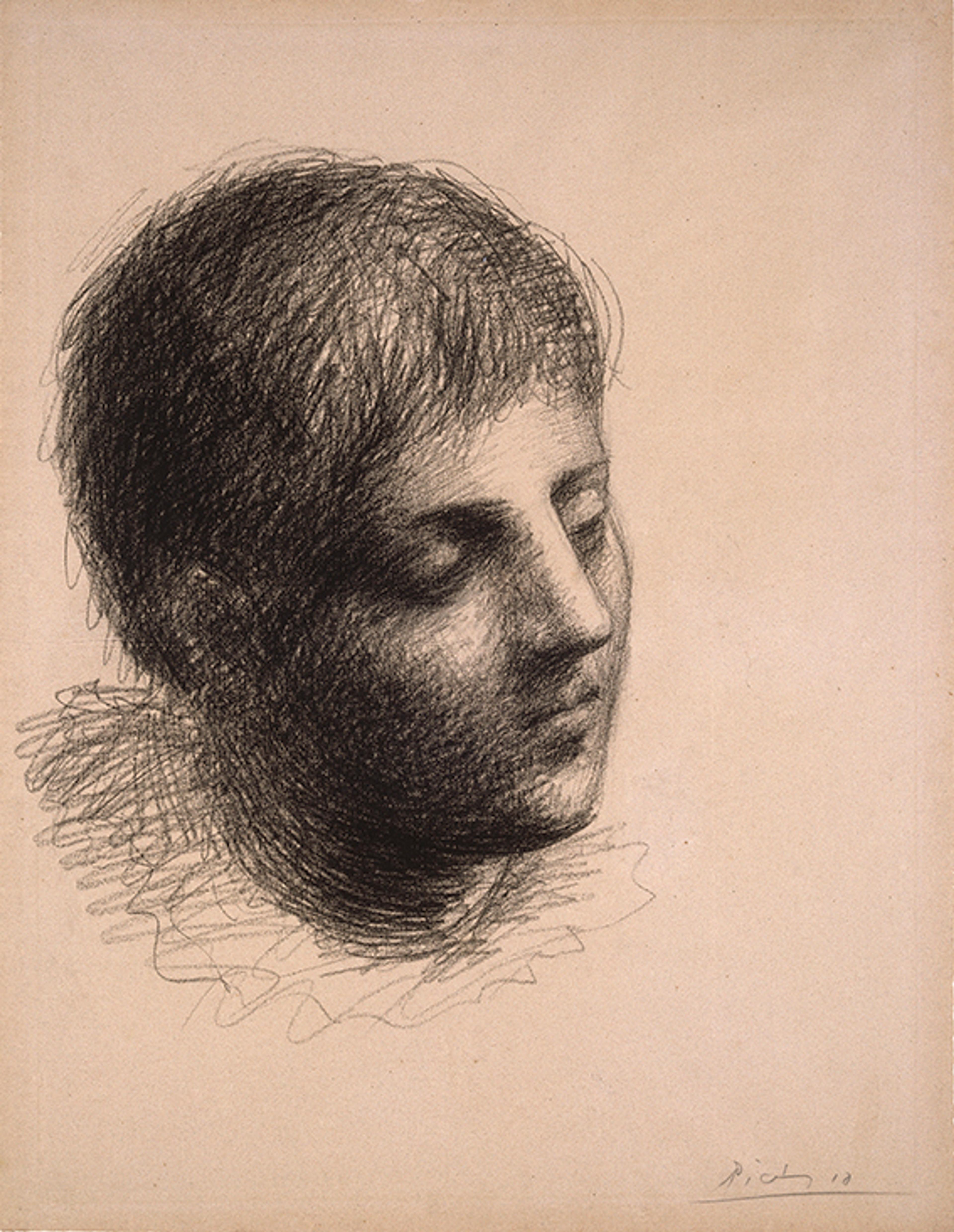

There is an immediacy and intimacy to works on paper that seems to bring us especially close to an artist’s vision and process. Drawn directly on paper or a printing plate, in broad gestures or precise marks, these works convey the vivid presence of the artist’s hand. Rembrandt to Picasso: Five Centuries of European Works on Paper highlights more than a hundred European drawings and prints from our exceptional collection, many of which are on view for the first time in decades.

From the remarkably spontaneous etchings of Rembrandt, through the bold graphite lines of Pablo Picasso, the exhibition explores the roles of drawing and printmaking within artists’ practices, encompassing a variety of modes, from studies to finished compositions, and a range of genres, including portraiture, landscape, satire, and abstraction. Working on paper, artists have captured visible and imagined worlds, developed poses and compositions, experimented with materials and techniques, and expressed their personal and political beliefs. Other featured artists include Albrecht Dürer, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Francisco Goya, Berthe Morisot, Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet, Vincent van Gogh, Käthe Kollwitz, and Vasily Kandinsky.

In conjunction with the exhibition One: Titus Kaphar, on view in the adjacent gallery, excerpts from a conversation with contemporary artist Titus Kaphar (b. 1976) accompany selected works here, addressing the often incomplete and difficult narratives presented by the predominantly white, male artists of the traditional Western art canon.

Rembrandt to Picasso: Five Centuries of European Works on Paper is curated by Lisa Small, Senior Curator, European Art, Brooklyn Museum.

Organizing department

Special Exhibition