Ancient Egyptian Art

1 of 23

Portions of these galleries will be closed November 10, 2025–January 30, 2026.

Our collection of ancient Egyptian art, one of the largest and finest in the United States, is renowned throughout the world. Egypt is the oldest continuously documented civilization on the African continent, and our collection, begun in 1902, tells the story of its art from its earliest known origins until the Roman period.

The ancient Egyptians were an Indigenous African people whose cultural and artistic origins in the Nile Valley can be traced back over 8,000 years. Joined over five millennia by other Africans from Nubia and Libya, as well as West Asians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans, their distinctly multicultural society produced an astonishing array of objects and structures.

Our Egyptian galleries contain more than 1,200 objects that include sculpture, reliefs, paintings, pottery, and papyri. On view are such treasures as a gilded wooden statuette of Amunhotep III, an exquisite chlorite head of a Middle Kingdom princess, a statue of queen Ankhnes-meryre holding her son Pepy II, and a terra-cotta statuette of a woman created over 5,000 years ago. Dedicated spaces highlight Tutankhamun’s youth and the city of Amarna, as well as pottery and figurines from ancient Egypt and Nubia.

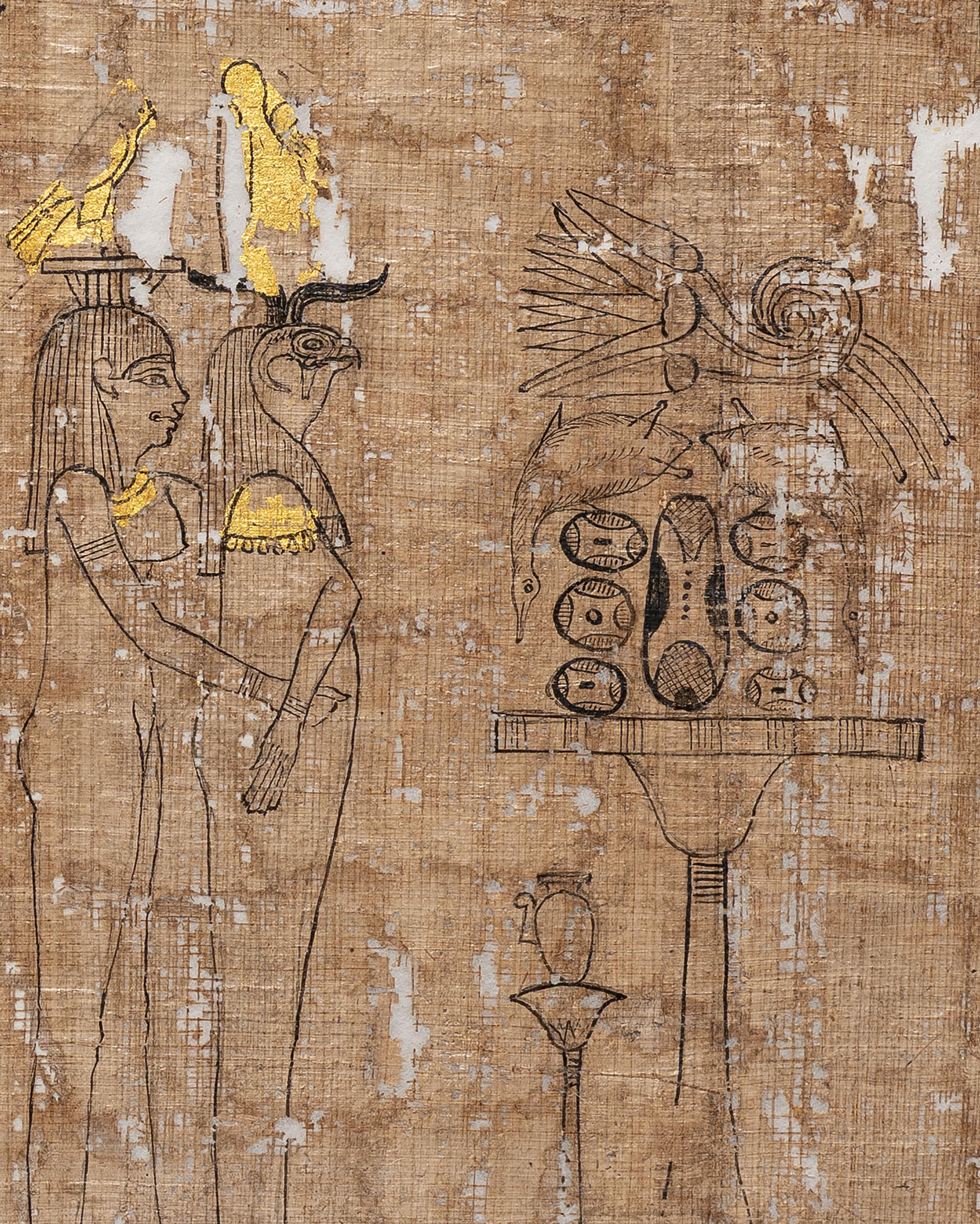

Also included is a newly refreshed funerary gallery that explores rituals and objects related to Egyptian afterlife beliefs. On view are the elaborately decorated coffin and mummy board of Pasebakhaienipet, mayor of Thebes; wall reliefs from the tomb of the vizier Nespeqashuty; several mummified individuals and animals; and a nearly 25-foot-long Book of the Dead scroll. On January 30, 2026, one of the world’s only complete and gilded Books of the Dead joins this space—on public display for the first time.

Location

Audio Guide

Listen to audio content with the Bloomberg Connects app.

This installation is organized by Edward Bleiberg, Curator of Egyptian Art, with Yekaterina Barbash, Curator, and Morgan Moroney, Assistant Curator, Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern Art.

Generous support for the installation of the Introduction and Early Egypt galleries as a part of the Brooklyn Museum’s Countdown to Launch initiatives is provided by the Elizabeth A. Sackler Museum Educational Trust, the Jerome Levy Foundation, the Frederick and Diana Elghanayan Family Foundation, and Richard A. Fazzini and Mary E. McKercher.

Organizing department

Egyptian, Classical, Ancient Near Eastern Art

![<i>Outer Coffin of Horus</i>, 796–771 B.C.E.. Wood, pigment, beeswax, plant resins, bitumen, and proteinaceous adhesives, Lid: 15 7/8 x 25 x 79 1/4 in. (40.3 x 63.5 x 201.3 cm) Box: 18 x 27 1/8 x 79 1/4 in. (45.7 x 68.9 x 201.3 cm) Box: 151 lb. (68.49kg) Lid and Base together: 30 7/8 x 27 1/8 x 79 1/4 in. (78.4 x 68.9 x 201.3 cm) [Note: this is 3 inches shorter than the two heights combined because the tongs on the base go into the slots of the lid]. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 37.1927Ea-b. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)](https://cms-images.brooklynmuseum.org/5fde120f3cf926a023c65ca09eea9aed327f5c0a-1200x1500.jpg?w=3840&q=75)