Vishnu Saving the Elephant (Gajendra Moksha). India, mid-18th century. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 81⁄16 x 59⁄16 in. (20.5 × 14.1 cm). Collection of Kenneth and Joyce Robbins

Vishnu Saving the Elephant (Gajendra Moksha). India, mid-18th century. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 81⁄16 x 59⁄16 in. (20.5 × 14.1 cm). Collection of Kenneth and Joyce Robbins

Vishnupada. Northern India or Pakistan, circa 500. Lapis lazuli, 2 × 43⁄8 x 33⁄4 in. (5.1 × 11.1 × 9.5 cm). Collection of Anthony d’Offay. Photo: Courtesy of John Eskenazi Ltd.

Vishnu’s footprints or, often, his feet (pada) are among the emblems used to stand in for his full body. The god’s feet are particularly significant because he took three steps across earth, sky, and heaven. As a mark left behind, the footprints celebrate Vishnu’s influence and presence. To touch someone’s feet is a gesture of humility and respect, so followers often bow down to touch Vishnupada that have been enshrined.

Miniature Shrine for an Icon or Ritual Object. Southern India, 19th century. Gold, rubies, emeralds, diamonds, and pearls, 51⁄8 x 35⁄8 x 31⁄8 in. (13 × 9.2 × 8 cm). Collection of Susan L. Beningson

This shrine is a miniature of a traditional Indian throne, which was designed to elevate the sitter while allowing him to sit in a cross-legged position. The parasol is an ancient mark of authority and often appeared over thrones, even indoors. This throne probably held a small icon, perhaps representing the infant Krishna, Vishnu on the serpent Shesha, or another figure in a seated or reclining position. It is also the right size to hold a shaligrama, the chakra-shaped fossil shell that is worshipped as a naturally occurring emblem of Vishnu.

Krishna and Radha in a Grove. Northern India (Rajasthan, Kota), circa 1720. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 71⁄2 x 43⁄8 in. (19 × 11.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon B. Polsky Fund, 2003.178a, b. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY

Until about 1000 C.E. , Hindu literature described Krishna’s romantic exploits as fully egalitarian: he gave love to every gopi equally. Later Hindu literature describes a favorite gopi, named Radha. She is Krishna’s great love but she is married, so the two must meet in secret. Devotees are invited to imagine themselves as Radha, involved in an intense affair with God. Some of India’s most beautiful paintings have treated the relationship between Krishna and Radha, celebrating their love and the bounteous pastoral setting in which it blossoms.

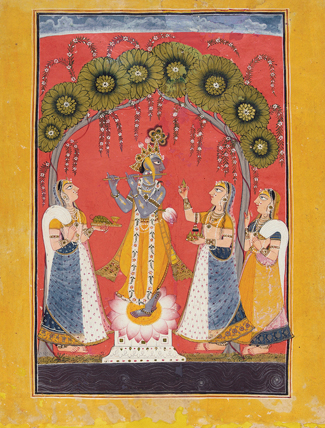

Krishna Fluting for the Gopis, page from an illustrated Dashavatara series. Northern India (Punjab Hills, Mankot), circa 1730. Opaque watercolor and gold on paper, 101⁄4 x 8 in. (26 × 20.3 cm). Collection of Catherine and Ralph Benkaim

Krishna is the most popular of Vishnu’s avatars, and many of his followers believe that he is far more than an avatar. Krishna lives on earth as a prince, but he grows up in a pastoral community. Like many herdsmen, Krishna plays the flute. His divine music has a mesmerizing effect, particularly over women, although animals and even rivers are also said to stop what they are doing in order to listen. Many texts describe the gopis, or milkmaids, stumbling through the woods toward the music’s source. Here they surround the flute-playing god, worshipping him, flirting with him, and adoring his beauty.

Yoga-Narasimha. Southern India (Tamil Nadu, Thanjavur region), Chola Period, 12th century. Bronze, 183⁄4 x 13 × 91⁄2 in. (47.6 × 33 × 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Samuel Eilenberg Collection, Bequest of Samuel Eilenberg, 2002.284.4. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY

Narasimha the half man, half lion is Vishnu’s most aggressive avatar. He is shown here seated in meditation. In the Hindu tradition, meditation and physical power are closely related. Long sessions of contemplation are said to build up heat and energy in the body and mind of the practitioner. For devotees of Vishnu, the Narasimha avatar is the embodiment of kinetic energy, so it is not surprising to see that he, more than any other avatar, is associated with the yogic practices that help develop and harness that energy.

Varaha Rescuing the Earth, page from an illustrated Dashavatara series. India, circa 1730–40. Opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, 101⁄2 x 81⁄8 in. (26.7 × 20.6 cm). Brooklyn Museum Collection, by exchange, 41.1026

Hindus believe that Vishnu has descended to earth on at least ten occasions, in smaller bodies known as avatars. Varaha the boar avatar saved the earth from being submerged in the primordial ocean. This painting of the Varaha story shows the boar balancing the earth on his head. The earth is here represented as a landmass, whereas in many other depictions the earth is a goddess. Varaha stands on the demon Hayagriva, signifying victory over the evil forces that wished the earth to drown.

Vishnu in His Cosmic Sleep. Central India (Madhya Pradesh), circa 12th century. Sandstone, 149⁄16 x 279⁄16 in. (37 × 70 cm). Private collection, Europe. Photo: Courtesy of Oliver Forge and Brendan Lynch Ltd.

Worshippers of Vishnu believe that their god created the cosmos while he reclined on a giant serpent that was floating on the primordial ocean. A lotus grew from Vishnu’s navel and from it emerged the god Brahma, who created the world. Here Brahma appears rather small and insignificant compared to Vishnu and his wife. Snakes and a sea monster along the base recall the primordial ocean, while along the top are figures of Vishnu’s ten avatars (starting with Matsya the fish and ending with the equestrian Kalki), followed by the nine planetary deities. The relief indicates that the planets, like the avatars and Brahma, have sprung from Vishnu.

Lakshmi Massaging the Foot of Vishnu. Northern India (Punjab Hills, possibly Basohli), circa 1765–70. Opaque watercolor, gold, and silver on paper, 103⁄4 x 73⁄8 in. (27.3 × 18.7 cm). Collection of Catherine and Ralph Benkaim

In this image, Lakshmi dutifully tends to her enthroned husband while a female servant whisks away flies. An inscription on the reverse of the painting identifies the artists, one of whom, Nainsukh, is celebrated for revolutionizing painting styles in the Punjab Hills with his preference for delicate brushwork and naturalistic poses. Nainsukh’s touch is readily apparent in his depiction of the god, who has the usual straight posture and blue skin but sits in a more relaxed pose than we find in most other images.

Lakshmi-Narayana. Northern India (Rajasthan), 10th century. Sandstone, 46 × 23 × 11 in. (110.5 × 57.2 × 17.8 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchase Gift of the Charles Bloom Foundation, Inc., 86.191

When Vishnu is shown with one wife, the pair is usually called Lakshmi-Narayana: Lakshmi is the goddess of good fortune, and Narayana is another name for Vishnu. In most representations of divine couples, the goddess is much smaller than the god, but in this image Lakshmi is almost the same size as Vishnu. Their embrace, their exchange of gazes, and the synchronized sway of their bodies (a rare feature for Vishnu) all point to the happiness that can be achieved when male and female qualities meet in a balanced union.

Vishnu Flanked by His Personified Attributes. Northern or central India, 12th century. Sandstone, 401⁄2 x 225⁄8 x 8 in. (103 × 57.7 × 20.3 cm). Krannert Art Museum and Kinkead Pavilion, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Gift of Ellnora D. Krannert, 1969-10-1

This complex stele with Vishnu surrounded by other deities includes two personifications of his weapons, standing immediately next to the god at either side. Shankhapurusha (the conch) and Chakrapurusha (also known as Sudarshana the discus) hold and gesture toward their attributes, which also appear in Vishnu’s two left hands. Vishnu carries the mace in his right hand, but he does not hold the lotus; instead he raises his lower right hand in a gesture that means “do not fear.” The various other figures are the attendants of the god. Vishnu’s straight posture distinguishes him from the many bending, swaying bodies of those around him.

Two-Sided Stele with Vishnu (Flanked by Personified Attributes) and Durga. Northern or Eastern India, circa 7th century. Sandstone, height 431⁄4 in. (110 cm). Private collection

On one side of this piece (pictured), Vishnu holds a lotus bud and conch in his front hands while his rear hands rest on his two personified weapons. Sudarshana Chakra, the discus, and the goddess Gadadevi, who is the mace, can be identified by the weapons behind their heads. On the other side is an image of the warrior goddess Durga, who is sometimes described as Vishnu’s sister but more often worshipped separately. This unusual two-sided stele was probably set up on a freestanding altar to serve a community with sectarian affiliations to both Vishnu and Durga.

Vishnu. Eastern India (West Bengal) or Bangladesh, Gupta period, 5th century. Terracotta, 357⁄16 x 175⁄16 in. (90 × 44 cm). Private collection

This image of Vishnu shows him in his primary form, standing erect with three of his four attributes: the wheel or chakra, the conch shell, and the mace. His fourth hand, now missing, probably held a lotus bud. This terracotta sculpture is unusual because it is freestanding (most clay and stone sculpture was made to line temple walls) and because it has a shiny dark surface, probably created by painting the clay black and then polishing it. Attached to a cart through the holes in its base, the image could be transported for religious processions.

Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior

June 24–October 2, 2011

Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior is the first major museum exhibition to focus on Vishnu, one of Hinduism’s three major deities. Presenting approximately 170 paintings, sculptures, and ritual objects that were made in India between the fourth and twentieth centuries, this exhibition serves as a brief survey of Hindu art styles as well as an examination of the Vaishnava (Vishnu-worshipping) tradition.

Known as Hinduism’s gentle god, Vishnu is easily recognized in paintings by his blue skin. While he is an interesting figure in his primary form, the complexity of Vishnu’s character becomes clear when he assumes new forms, known as avatars, in order to save the earth from various dangers. Vishnu’s ten avatars reveal the multiplicity of ways that one can envision and interact with the divine.

The first section of the exhibition introduces Vishnu in his primary form, with subsections dedicated to his attributes, his consorts, and his legends. The second section examines his avatars, as a group and then individually. The avatars that are more frequently celebrated in art are fully represented in the exhibition, with substantial subsections dedicated to Rama and Krishna. The third section shows some of the ways in which Vishnu has been worshipped, with images of temples and ritual objects.

Vishnu: Hinduism’s Blue-Skinned Savior has been organized by the Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, Tennessee, and curated by Joan Cummins, Lisa and Bernard Selz Curator of Asian Art, Brooklyn Museum.

Generous support is provided by the Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Exhibition Fund and the Estate of Bertram H. Schaffner.

Additional funding has been provided by the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation; The Selz Foundation, Inc.; Katharine and Rohit Desai; Gary Smith and Teresa Kirby; Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon Polsky; Ruth and Richard Dickes; the Alvin E. Friedman-Kien Exhibition Fund; the Asian Art Council; an anonymous donor; and other generous supporters.

Media sponsor