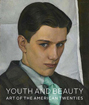

Luigi Lucioni (American, 1900–1988). Paul Cadmus, 1928. Oil on canvas, 16 × 121⁄8 in. (40.6 × 30.8 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, 2007.28

Luigi Lucioni (American, 1900–1988). Paul Cadmus, 1928. Oil on canvas, 16 × 121⁄8 in. (40.6 × 30.8 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, 2007.28

Joseph Stella (American, 1877–1946). The Amazon, 1925–26. Oil on canvas, 27 × 22 in. (68.6 × 55.9 cm). The Baltimore Museum of Art, Purchased with exchange funds from the Edward Joseph Gallagher III Memorial Collection, BMA 1991.13. Photo: Mitro Hood

For all of its ties to the Italian Renaissance profile portraits that Joseph Stella deeply admired, The Amazon more immediately evokes American movie goddesses and the glamorous exemplars of American fashion featured in ubiquitous magazine ads. Building on two earlier portrait drawings of a sensuous young woman named Kathleen Millay, Stella created this profile superportrait, which he later described as an homage to the “beauty and efficiency” of American womanhood and her “conquests obtained in every domain.”

Gerald Murphy (American, 1888–1964). Razor, 1924. Oil on canvas, 321⁄16 x 361⁄2 in. (81.4 × 92.7 cm). Dallas Museum of Art, Foundation for the Arts Collection, Gift of the Artist. © Estate of Honoria Murphy Donnelly / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

With its almost “pre-Pop” billboard-style oversizing and graphic boldness, Gerald Murphy’s Razor suggests the heraldic crest of a modern American man, whose necessary tools are a Gillette safety razor, a Parker Big Red pen, and Three Stars matches. As the son of the head of the Mark Cross company, known for fine leather goods, Murphy was attuned to product design, as well as to style and status. After taking up painting in Paris in 1921, he borrowed from the new, reductive decorative aesthetic of Purism to celebrate American machine-age design for an enthusiastic postwar French audience. The painting also resonates in the context of Murphy’s obsessive self-fashioning as ultramodern and unconventional—an expression, in part, of his own bisexuality.

Imogen Cunningham (American, 1883–1976). Nude, 1923. Gelatin silver print, 615⁄16 x 91⁄2 in. (17.6 × 24.2 cm). Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson, Purchase. © (1923), 2010 The Imogen Cunningham Trust, www.ImogenCunningham.com

The bodies featured in this sensuous image are those of the photographers Margrethe Mather and Edward Weston, who had been linked romantically and professionally several years before they posed for the photographer Imogen Cunningham in Weston’s Glendale, California, studio. Cunningham documented the pair’s connectedness in this precisely framed composition of two bodies in responsive contact. A daring subject for any artist (let alone a young woman) in twenties America, Cunningham’s Nude reaffirmed the equation of physical contact and creative agency.

Nickolas Muray (American, 1892–1965). Gloria Swanson, circa 1925. Gelatin silver print, 123⁄4 x 93⁄8 in. (32.4 × 23.8 cm). George Eastman House, International Museum of Photography and Film, Rochester, New York, Gift of Mrs. Nickolas Muray. © Estate of Nickolas Muray

One popular trope that emerged during the twenties to suggest a beautiful woman’s depth was to represent her holding her face, masklike, in her hands, as if to signal the simultaneous acts of self-invention and containment. In this captivating image of the young Gloria Swanson, the portrait photographer Nickolas Muray recorded the sultry perfection of the actress’s face as though it were held delicately in place by her sensuously bare shoulder and precisely placed hand.

Aaron Douglas (American, 1899–1979). Congo, circa 1928. Gouache and pencil on paper board, 143⁄8 x 91⁄2 in. (36.5 × 24.1 cm). North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, Gift of Susie R. Powell and Franklin R. Anderson

A passionate advocate of jazz as a new mode of African American expression based in deep emotions and black cultural traditions, Aaron Douglas pictured a scene of rhythm-induced abandon in Congo, an illustration for the novel Black Magic, in which the French writer Paul Morand exploited the primitivist vogue for its sensationalism. Here, Congo, an African American performer modeled on the uninhibited Josephine Baker, joins an ecstatic drumming and dance ritual in a Parisian bar. She foresees her own death in a vision of the Mississippi and her Creole grandmother, spotlit here in the electric beam of her gaze.

Edward Hopper (American, 1882–1967). Lighthouse Hill, 1927. Oil on canvas, 291⁄16 x 401⁄4 in. (73.8 × 102.2 cm). Dallas Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Maurice Purnell, 1958.9. © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art

Edward Hopper painted Lighthouse Hill during his first stay in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, a remote strip of land extending twelve miles into the Atlantic that Hopper reached in a newly acquired used Dodge. Seen from a dramatically low vantage point and in a strong, raking light, the massive Eastern Light and the steep-roofed house appear almost apparitional, suggesting the exposure of the site and the elemental existence of its inhabitants. Lighthouse Hill embodied the honesty, intensity, and “austerity” that twenties critics valued.

Winold Reiss (American, 1886–1953). Black Prophet, 1925. Pastel on Whatman board, 30 × 22 in. (76.2 × 55.9 cm). Private collection. © The Reiss Trust

Black Prophet, also known as The African, belongs to a significant group of portraits completed by Winold Reiss for Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro, a special 1925 issue of the journal Survey Graphic celebrating Harlem’s rising urban culture. The sitters were chosen by Alain Locke and other leaders of the New Negro movement, who sought to expand and dignify the image of black Americans. Distinguished by his heroic form and traditional dress, this sitter represented one element of what Locke called the “race capital” of Harlem, with its “concentration of so many diverse elements of Negro life,” including “the African, the West Indian [and] the Negro American.”

George Copeland Ault (American, 1891–1948). Brooklyn Ice House, 1926. Oil on canvas, 24 × 30 in. (61 × 76.2 cm). Newark Museum, Purchase 1928 The General Fund, 28.1760

George Ault’s distinctly unpeopled Brooklyn Ice House is typical of the reductive twenties realism praised by critics for its pleasing blend of modernism and naïveté. The impulse toward simplification offered a link to a simpler American past in which the individual had thrived. Ault’s strange but forceful palette and the hermetically closed forms of the industrial structure lend the image a mysterious air. He relieved the strict geometries of the architecture with the brittle forms of leafless trees, so common to twenties landscape imagery, and with the oddly lyrical plume of black smoke—the picture’s most emphatic sign of life.

George Wesley Bellows (American, 1882–1925). Two Women, 1924. Oil on canvas, 57 × 60 in. (144.8 × 152.4 cm). Portland Museum of Art, Maine, Lent by Karl Jaeger, Tamara Jaeger, and Karena Jaeger, 26.2004. © Bellows Trust

This ambitious work is an homage to an Italian Renaissance painting by Titian titled Sacred and Profane Love, circa 1514 (Galleria Borghese, Rome), in which a nude and a clothed figure are paired to contrast pure love (unclothed) with its worldly counterpart. In the twenties, when Freudian ideas were as current as the latest fashions, viewers most likely read George Bellows’s variation on Titian’s theme as an embodiment of the vying impulses of sexual openness and repression. The assertively lit nude and her clothed counterpart appear in the well-recognized parlor setting of Bellows’s home in rural Woodstock, New York.

Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties

October 28, 2011–January 29, 2012

How did American artists represent the Jazz Age? The exhibition Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties brings together for the first time the work of sixty-eight painters, sculptors, and photographers who explored a new mode of modern realism in the years bounded by the aftermath of the Great War and the onset of the Great Depression. Throughout the 1920s, artists created images of liberated modern bodies and the changing urban-industrial environment with an eye toward ideal form and ordered clarity—qualities seemingly at odds with a riotous decade best remembered for its flappers and Fords.

Artists took as their subjects uninhibited nudes and close-up portraits that celebrated sexual freedom and visual intimacy, as if in defiance of the restrictive routines of automated labor and the stresses of modern urban life. Reserving judgment on the ultimate effects of machine culture on the individual, they distilled cities and factories into pristine geometric compositions that appear silent and uninhabited. American artists of the Jazz Age struggled to express the experience of a dramatically remade modern world, demonstrating their faith in the potentiality of youth and in the sustaining value of beauty. Youth and Beauty will present 140 works by artists including Thomas Hart Benton, Imogen Cunningham, Charles Demuth, Aaron Douglas, Edward Hopper, Gaston Lachaise, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Luigi Lucioni, Gerald Murphy, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Weston.

The exhibition was organized by Teresa A. Carbone, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of American Art, Brooklyn Museum.

Sponsored by

Youth and Beauty: Art of the American Twenties is also made possible by the Henry Luce Foundation. Additional support has been provided by the Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Exhibition Fund, The Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz Foundation for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Arts, the Robert Lehman Foundation, the Wyeth Foundation for American Art, the Steven A. and Alexandra M. Cohen Foundation, Inc., Sotheby’s, the Norman M. Feinberg Exhibition Fund, and an anonymous donor. This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

The accompanying catalogue is supported by the Henry Luce Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, The Mr. and Mrs. Raymond J. Horowitz Foundation for the Arts, Furthermore: a program of the J.M. Kaplan Fund, and a Brooklyn Museum publications endowment established by the Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Foundation and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Print media sponsor