Timeline of Independence

The decolonization of the African continent has been a centuries-long journey that witnessed dramatic upheavals in the political and socioeconomic lives of hundreds of millions of people.

During the second half of the twentieth century, colonial governments, impaired by violence and widespread unrest, rapidly transitioned to becoming independent states. Referred to as the “Year of Africa,” 1960 was a turning point in which more than a dozen African countries would secure their independence. By the decade’s end, Africa had forty-eight independent nations. However, it would take another three decades before the entire continent would achieve emancipation from colonial rule.

This timeline provides an overview of Africa’s fifty-four nations, plus one disputed territory, on their journey to independence and the decades following decolonization. Political and cultural conflict are common themes within these nations, which are the result of centuries of colonial intervention. Despite this, the seminal journeys of each country are representations of their own rich historical legacies and fight toward political sovereignty and self-governance.

1847

LIBERIA

July 26, 1847, from the American Colonization Society

Liberia was established as a colony by the American Colonization Society, an organization founded to urge and support the migration of emancipated and freeborn Black Americans to the African continent. The early settlers, known as Americo-Liberians or Congaus, imposed many of the systems promoted in the United States, including plantations. In 1847, the settlers issued a Declaration of Independence and passed a constitution, initiating Americo-Liberian self-governance.

1910

SOUTH AFRICA

May 31, 1910 / May 31, 1961, from the United Kingdom / April 27, 1994, voting independence post apartheid

After two centuries of colonial expansion, resource extraction, and dominance by the Dutch and British, the Union of South Africa was established and declared a self-governing dominion of the British Empire on May 31, 1910. With independence, anti-Black and anti-Indigenous racism in the form of segregation, land-ownership restrictions, and disenfranchisement was codified into law. The provisions were later strengthened and expanded upon with the establishment of apartheid in 1948. While South Africa left the British Commonwealth of Nations (the political association of former British colonies) in 1961, it was not until the fall of apartheid in April 1994 that the country experienced true democratization.

1922

EGYPT

February 28, 1922, from the United Kingdom

While the United Kingdom first issued a unilateral declaration of Egyptian sovereignty on February 28, 1922, their occupation of the country would continue unabated for several decades. It was not until June 18, 1953, following a revolution helmed by military officer Gamal Abdel Nasser, that the Kingdom of Egypt was formally abolished and declared an autonomous republic. Egyptian independence ushered in a wave of pan-Arabist sentiment and decolonization efforts that spread throughout the Middle East and North Africa.

ETHIOPIA

Maintained independence

Despite European imperial interests, Ethiopia was never colonized and maintained independence throughout the colonial period. In March 1896, the First Italo-Ethiopian War under Emperor Menelik II culminated in Italian defeat at the Battle of Adwa, securing Ethiopia’s place as Africa’s oldest independent nation. During World War II, British and other Allied powers (including Ethiopian troops) once again defeated Italian forces who had occupied Ethiopia in 1935, under the direction of Benito Mussolini. In May 1941, Emperor Haile Selassie returned to the throne during continued guerrilla fighting by Italian forces and under British military administration. In December 1944, the United Kingdom and Ethiopia signed the second Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement, reestablishing Ethiopian sovereignty.

1951

LIBYA

December 24, 1951, from France and the United Kingdom

With the outbreak of World War II, Libya, then an Italian colony, became the setting for a brutal North African campaign that culminated in 1943, with Italian defeat (with the regions of Italian Cyrenaica and Tripolitania later merging to form Italian Libya) and Allied (Franco-British) occupation of Libya. In December 1951, Libya declared independence and established itself as a constitutional monarchy. A brief period of prosperity followed the discovery of oil in 1959. However, complaints about the use of oil proceeds by the Libyan monarch, Idris I, to benefit his own family led to his deposition by rebel officers in 1969. The coup’s leader, Muammar Gaddafi, quickly established a violent authoritarian regime that ruled Libya until 2011.

1956

SUDAN

January 1, 1956, from the United Kingdom and Egypt

By 1898, present-day Sudan was administered by the United Kingdom and Egypt (then occupied by British forces). In 1946, British administrators determined that northern and southern Sudan, which had been administered as separate provinces, should be unified under one governmental authority under which northern Sudanese elites would be integrated into the colonial government. An agreement enabling Sudanese self-government was reached between the United Kingdom and Egypt in 1953. Three years later, on January 1, the British and Egyptian governments officially recognized Sudan’s independence. By that time, however, the disparity and power imbalance between the north’s and the south’s development led to the First Sudanese Civil War.

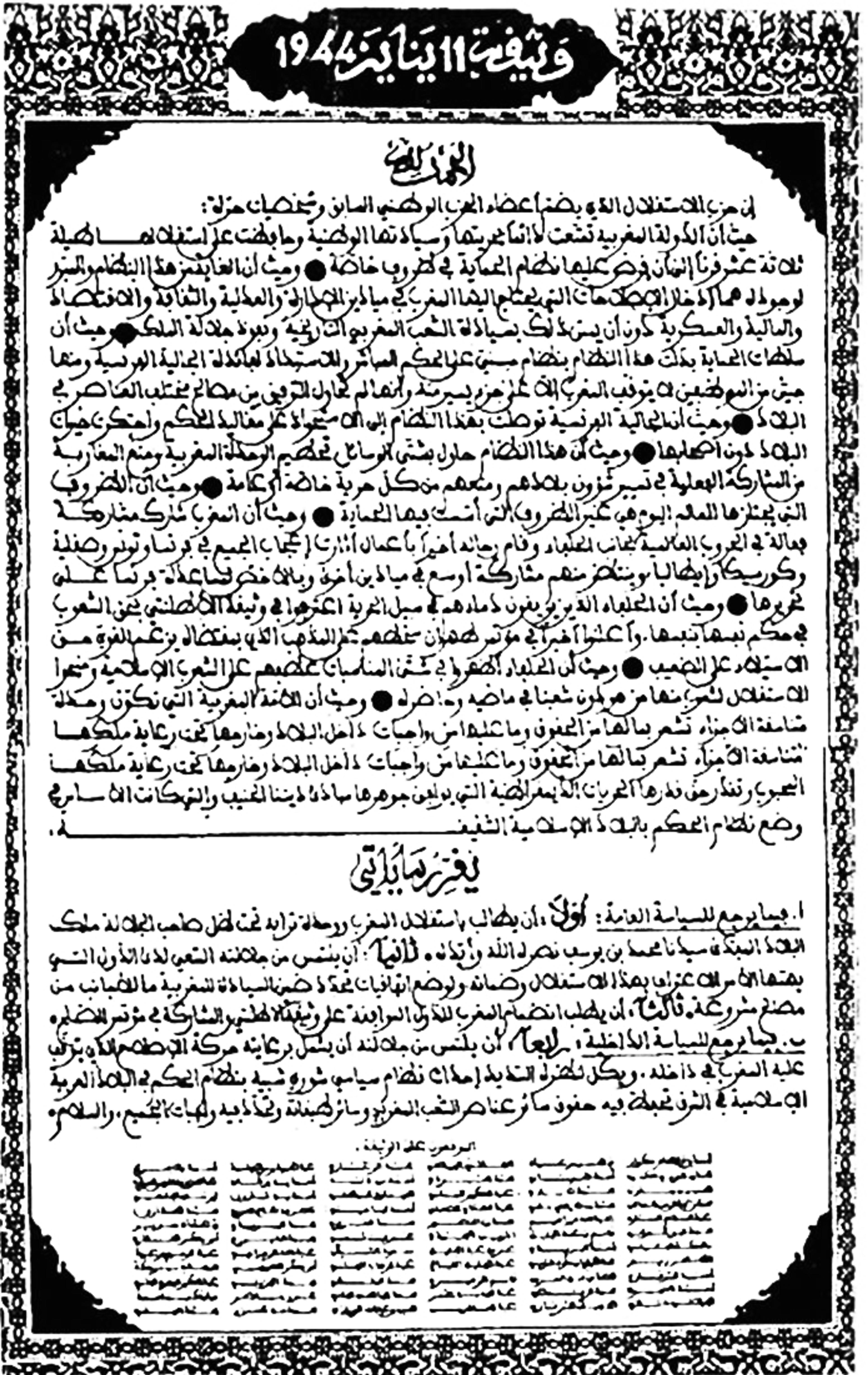

MOROCCO

March 2, 1956, from France

From 1666 to the present, the ʿAlawī dynasty has ruled Morocco. In 1884, the Spanish government created a protectorate of Ceuta and other coastal areas after waging a successful war against Morocco in 1860 to strengthen its claim. France colonized the remaining part of Moroccan territory as a protectorate in 1912. Following years of resistance to French rule, the Kingdom of Morocco regained sovereignty in 1956, although Spain continues to control the coastal territories of Alhucemas, Ceuta, the Chafarinas Islands, Melilla, and Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera today.

TUNISIA

March 20, 1956, from France

After three centuries of Ottoman rule, France invaded Tunisia in 1881 and colonized it as a protectorate in 1883. The Tunisian independence movement gained momentum following World War I. In 1934, Habib Bourguiba established the Neo-Destour Party, which led the Tunisian independence movement, resulting in his inaugural presidency. After Tunisia gained independence in 1956, Bourguiba became the country’s leader for three decades.

1957

GHANA

March 6, 1957, from the United Kingdom

Ghana’s independence movement was led by Kwame Nkrumah, who established the Convention People’s Party (CPP) in the British colony of the Gold Coast. The CPP campaigned for independence through strikes and other nonviolent actions and would go on to win thirty-four out of thirty-eight seats in the Gold Coast’s Legislative Council in the 1951 general election. As a result of a United Nations plebiscite in 1956, British Togoland and the Gold Coast became a united territory. Under Nkrumah’s leadership and the CPP, the former British colonies of Asante and the Northern Territories, along with British Togoland and the Gold Coast, merged to form the Republic of Ghana upon independence in 1957.

1958

GUINEA

October 2, 1958, from France

Guinea was ruled by a series of African empires before France colonized the region in the late nineteenth century. French colonial rule exploited Guinea’s abundant natural resources with forced labor and harsh taxation. In 1958, the French Fourth Republic under the fourth constitution of the French republican government collapsed, replaced by the French Fifth Republic under the fifth constitution of the French republican government and France’s current political system, which gave the colonies the option to establish immediate independence. Unlike many other French colonies, Guinea’s population overwhelmingly voted for independence under the leadership of their first president, Sékou Touré.

1960

CAMEROON

January 1, 1960, from France / October 1, 1961, from the United Kingdom

Colonized by Germany in the late nineteenth century, Cameroon was transferred to French and British administration following World War I. Although French and British Cameroon had different trajectories, both territories were exploited for their natural resources and remained dependent on European nations for finished goods. World War II sparked a surge of nationalism in Cameroon, culminating in the establishment of the Cameroon People’s Union (UPC), founded by Ruben Um Nyobè in 1948 to promote unification. In 1955, France banned the UPC for its nationalist sentiments, sparking a seven-year civil war. French Cameroon gained independence in 1960, and a year later, British Cameroon’s southern portion was united with it (with northern British Cameroon joining Nigeria).

SENEGAL

April 4, 1960, from France

In 1958, the French Fourth Republic under the fourth constitution of the French republican government fell and was replaced by the Fifth Republic under the fifth constitution of the French republican government and France’s current political system, which granted greater autonomy to its colonies. This led to the establishment of the Mali Federation, which included both Senegal and French Sudan (present-day Mali). However, tensions led to the Federation dissolving within two years, resulting in Senegal’s independence on April 4, 1960, after more than three centuries of colonial rule.

TOGO

April 27, 1960, from France

As part of the Scramble for Africa, an imperial episode where Belgium, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain partitioned Africa into subsequent colonies, the German Empire declared the protectorate of Togoland in 1884. The German government and corporations quickly established plantations where Togolese were forced to work. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, British and French forces occupied Togo. After the war, the League of Nations mandated the United Kingdom and France administer the territory. In 1956, British Togoland voted to join the newly independent nation of Ghana. Four years later, in 1960, the territory that is today Togo declared its independence from France.

MADAGASCAR

June 26, 1960, from France

During World War II, Madagascar’s independence movement was fomented by opposition to France’s Vichy regime. Nationalist and decolonial sentiments led to a two-year Malagasy nationalist rebellion in 1947. France’s violent suppression of the rebellion and stoking of ethnic resentments continued to impact the nation following independence in 1960. It’s estimated that between 11,000 and 100,000 Malagasy were killed in the rebellion, depleting post-independence Madagascar of skilled workers and impacting its social fabric.

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

June 30, 1960, from Belgium

Prior to colonization, the Kongo, Luba, Lunda, and several other kingdoms occupied what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 1885, King Leopold II of Belgium claimed these lands for his own personal use (known as the Free State) and exploited them, killing millions of Congolese in the process due to inhumane and brutal working conditions. International pressure forced Leopold to give up the Congo Free State in 1908, allowing the Belgian government to take control and rename the region the Belgian Congo. The country gained independence from Belgium as the Republic of Congo in 1960 and was soon renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1964. In 1971, the country’s name changed once again to the Republic of Zaire and then back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1997.

SOMALIA

July 1, 1960, from the United Kingdom and Italy

Britain and Italy colonized present-day Somalia in the late nineteenth century, administering them as British Somaliland and Italian Somaliland. Following their independence in 1960, the former colonies merged to form the Republic of Somalia. However, after a civil war began in 1991, residents of British Somaliland have sought independence as the Republic of Somaliland, while Puntland residents in the northeast have sought autonomy since 1998.

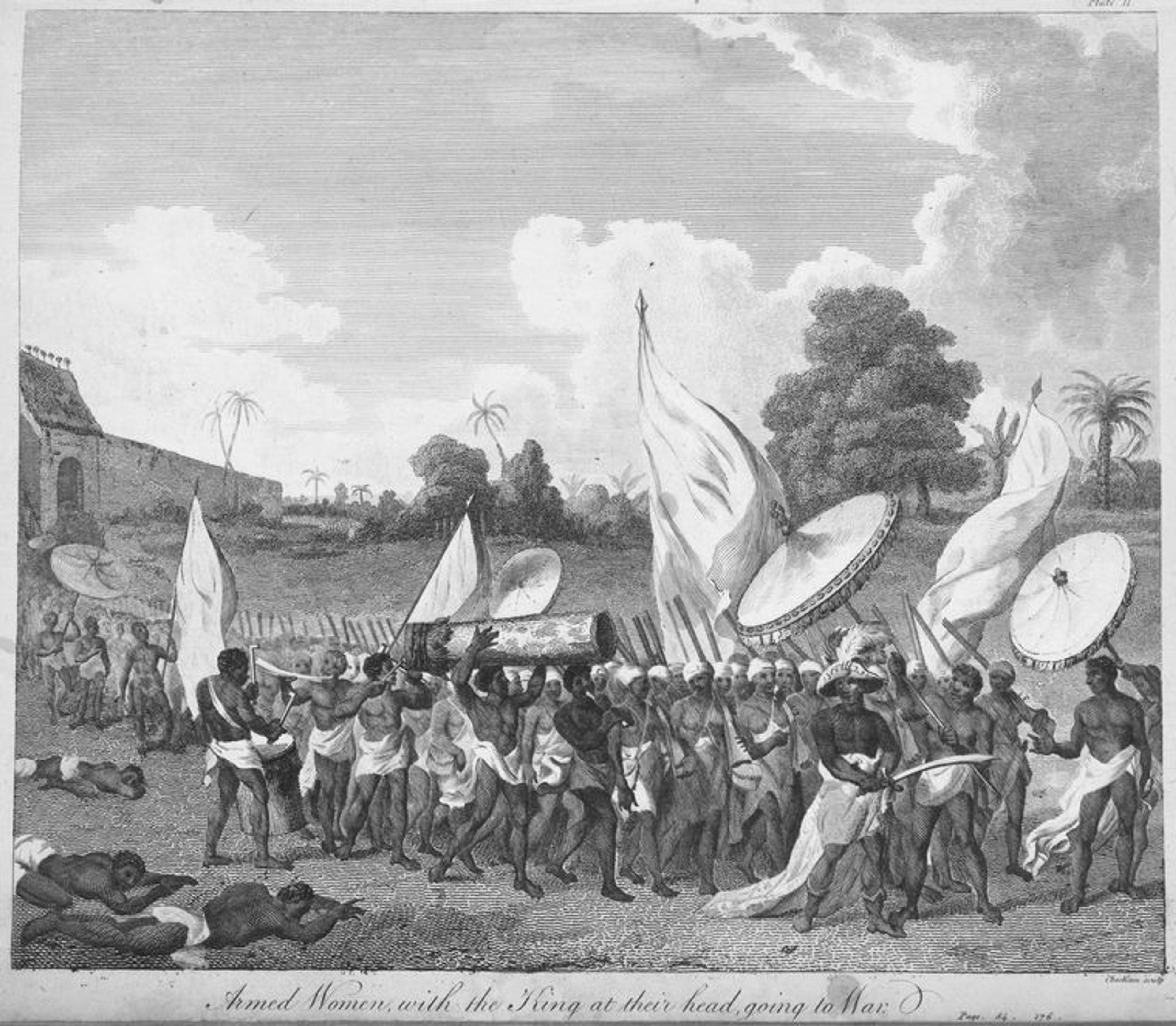

BENIN

August 1, 1960, from France

Dahomey, today known as Benin, gained independence from France on August 1, 1960, after nearly seventy years of colonial rule. Following its independence, however, local nationalist movements threatened to fragment the country. The post-independence period was marked by political instability, economic underdevelopment, and social unrest, exacerbated by a series of military coups and authoritarian regimes.

NIGER

August 3, 1960, from France

The former French colony of Niger gained independence on August 3, 1960, during a wave of decolonization across Africa. As a result of rising costs of colonial rule and nationalist activism following World War II, France granted Niger greater autonomy. In 1958, the French Fifth Republic, under the fifth constitution of the French republican government and France’s current political system, allowed colonies to declare immediate independence. In 1960, Niger broke all ties with France and became fully autonomous. After independence, Niger was ruled by a one-party regime for fourteen years, and political instability and economic mismanagement abounded.

BURKINA FASO

August 5, 1960, from France

Prior to colonization, Burkina Faso was home to many ethnic groups with diverse cultural and political systems. In 1895, France established Upper Volta as a protectorate during the Scramble for Africa, an imperial episode where Belgium, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain partitioned Africa into subsequent colonies. A number of political leaders led the struggle for independence, such as Maurice Yaméogo, who formed the Voltaic Democratic Union (UDV) in 1948, and intellectuals such as Joseph Ki-Zerbo, who founded the African Independence Party (PAI) in 1957.

CÔTE D’IVOIRE

August 7, 1960, from France

The region today known as Côte d’Ivoire was colonized by France in 1893 and remained under its administration until August 1960. French colonial policy mandated local assimilation to French culture, through the adoption of French language, customs, institutions, and laws. Côte d’Ivoire’s first agricultural trade union was founded by Félix Houphouët-Boigny in response to colonial policy that favored French plantation owners and disempowered farm workers, who often worked as forced laborers. Houphouët-Boigny quickly rose to prominence and was elected as Côte d’Ivoire’s first president upon independence.

CHAD

August 11, 1960, from France

First occupied by France in 1900, Chad was viewed by the French administration primarily as a source of labor as well as cotton. Having failed to effectively govern and maintain public confidence in the face of mounting decolonization movements, the French Fourth Republic under the fourth constitution of the French republican government collapsed in 1958. That year, Chad became an autonomous republic within the French Community, the constitutional organization comprising France and its remaining African colonies during decolonization, and, in 1960, the nation gained complete independence.

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC

August 13, 1960, from France

Colonial incursions by various European powers into the region today known as the Central African Republic (CAR) began during the last two decades of the nineteenth century, known as the Scramble for Africa, an imperial episode where Belgium, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain partitioned Africa into subsequent colonies. Following World War I, France annexed the territory and immediately began leasing it to private companies, who exploited both the local resources and Indigenous peoples. Laborers were forced to harvest rubber, coffee, and other commodities without compensation, and their families were held hostage until they met company quotas. In 1928, an anticolonial uprising was staged by an unprecedented coalition of thousands of forced laborers in the western region of Ubangi-Shari (present-day CAR). Following the collapse of the French Fourth Republic under the fourth constitution of the French republican government in 1958, Ubangi-Shari was granted autonomy within the French Community, the constitutional organization comprising France and its remaining African colonies during decolonization, and changed its name to the Central African Republic. CAR gained full independence from France on August 13, 1960, and in the months that followed the nation fell under one-party rule.

REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

August 15, 1960, from France

The Republic of the Congo was colonized by the French in 1880 and known as the French Congo. In 1908, the region became known as Middle Congo and was incorporated as a constituent part of French Equatorial Africa. It gained independence as the Republic of the Congo in 1960 but was renamed the People’s Republic of the Congo in 1969, when it became a Marxist-Leninist state. It returned to its status as the Republic of the Congo in 1991.

GABON

August 17, 1960, from France

Beginning in the sixteenth century, the region that is today Gabon served as a center of the transatlantic slave trade. Seeking to compete with Britain, which had established itself as the leading commercial manufacturer and trader in the Gulf of Guinea, France began making territorial inroads. By 1886, France had occupied Gabon, joining it with the French Congo. The French granted vast concessions to monopolistic corporations, which served as the state, while extracting petroleum, iron, manganese, and other natural resources. In 1910, alongside the French Congo, Ubang-Shari (later the Central African Republic), and Chad, Gabon became one of the four colonies to comprise French Equatorial Africa. During the interwar period, an anticolonial yet pro-French elite began to emerge as a political force. During the French Fourth Republic under the fourth constitution of the French republican government, this same pro-French political class held elected office locally and in the French Parliament. In 1958, the Fifth Republic, under the fifth constitution of the French republican government and France’s current political system, promised a new, liberatory approach to its colonies. Gabon became part of the French Community, the constitutional organization comprising France and its remaining African colonies during decolonization. Two years later, the nation gained full independence.

MALI

September 20, 1960, from France

Following colonization by France at the end of the nineteenth century, present-day Mali was known as French Sudan and administered as part of French West Africa. During the colonial period, the local population was subject to conscription, forced labor, and heavy taxation, which elicited several small-scale revolts. It was not until the passage of the French Reform Act in 1956, which granted self-government capabilities to its African territories, that decolonial and Pan-Africanist parties gained political clout within the country. In November 1958, alongside the establishment of the French Fifth Republic under the fifth constitution of the French republican government and France’s current political system, the region became an autonomous state within the French Community, the constitutional organization comprising France and its remaining African colonies during decolonization, and was renamed the Sudanese Republic. Two months later, the Sudanese Republic joined with Senegal to form the Mali Federation. Other francophone African nations did not heed the call to join the Federation, and shortly after gaining full independence from France in 1960, the union collapsed over irreconcilable political differences. A month later, in September of 1960, the Sudanese Republic became the independent Republic of Mali.

NIGERIA

October 1, 1960, from the United Kingdom

Beginning in the late fifteenth century, European powers established settlements and outposts throughout present-day Nigeria to support the trade of slaves, gold, and ivory. By the mid-nineteenth century, Britain had established an entrenched presence in the region, investing heavily in palm oil and Christian missionization. In 1861, the British annexed the port city of Lagos and within a year declared it a colony. Throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century, Britain continued to extend its sphere of influence in West Africa, declaring protectorates over the Oil Rivers and hinterlands of Lagos and establishing the Royal Niger Company to administer the lower Niger and the south of present-day Nigeria. It was not until 1914, however, that these disparate British holdings were united as the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria. British colonization of Nigeria was met with fierce opposition from various Indigenous peoples and kingdoms, who sought to maintain their autonomy and land rights. Following World War II, as a wave of Pan-African sentiment swept the continent, a broad anticolonial coalition that cut across ethnicity, class, and geographic region mobilized against British rule. In the wake of African decolonization, the British, fearing the loss of their colony, granted continued concessions and reforms until Nigeria was granted full independence in October 1960.

MAURITANIA

November 28, 1960, from France

After seizing coastal territory in 1817, France formally colonized Mauritania in 1904. The political elite leading Mauritania’s independence movement differed over the country’s orientation toward sub-Saharan Africa or North Africa and the Arab world. Moktar Ould Daddah was elected in 1958, heading the country’s first elected government. He then became president when the Islamic Republic of Mauritania became independent from France in 1960. While he was in power, he sought to maintain balance by joining both the Organization of African Unity (now the African Union) and the Arab League. Today, Mauritania is nearly entirely Muslim, with the majority of residents being Sunni.

1961

SIERRA LEONE

April 27, 1961, from the United Kingdom

Sierra Leone’s capital, Freetown, was first settled in 1787 by four hundred formerly enslaved African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, Africans, Southeast Asians, and British-born Black people sent from London, England, as part of the Committee for the Relief of the Black Poor, spearheaded by British abolitionist Granville Sharp. The “Province of Freedom” was established on land purchased from the precolonial Kingdom of Koya Temne in the north of present-day Sierra Leone. Founded in 1792, the area was officially named Freetown, which Britain took as a colony in 1808 along with its surrounding areas in 1896. Following World War II, nationalist pressure forced the British government to introduce democratic institutions, eventually resulting in the establishment of the independent Dominion of Sierra Leone, which later became the Republic of Sierra Leone in 1961. Between 1991 and 2002, a brutal civil war killed fifty thousand people and displaced more than two million. After decades of violence, Sierra Leone has held democratic elections since 1998, resulting in substantial economic growth.

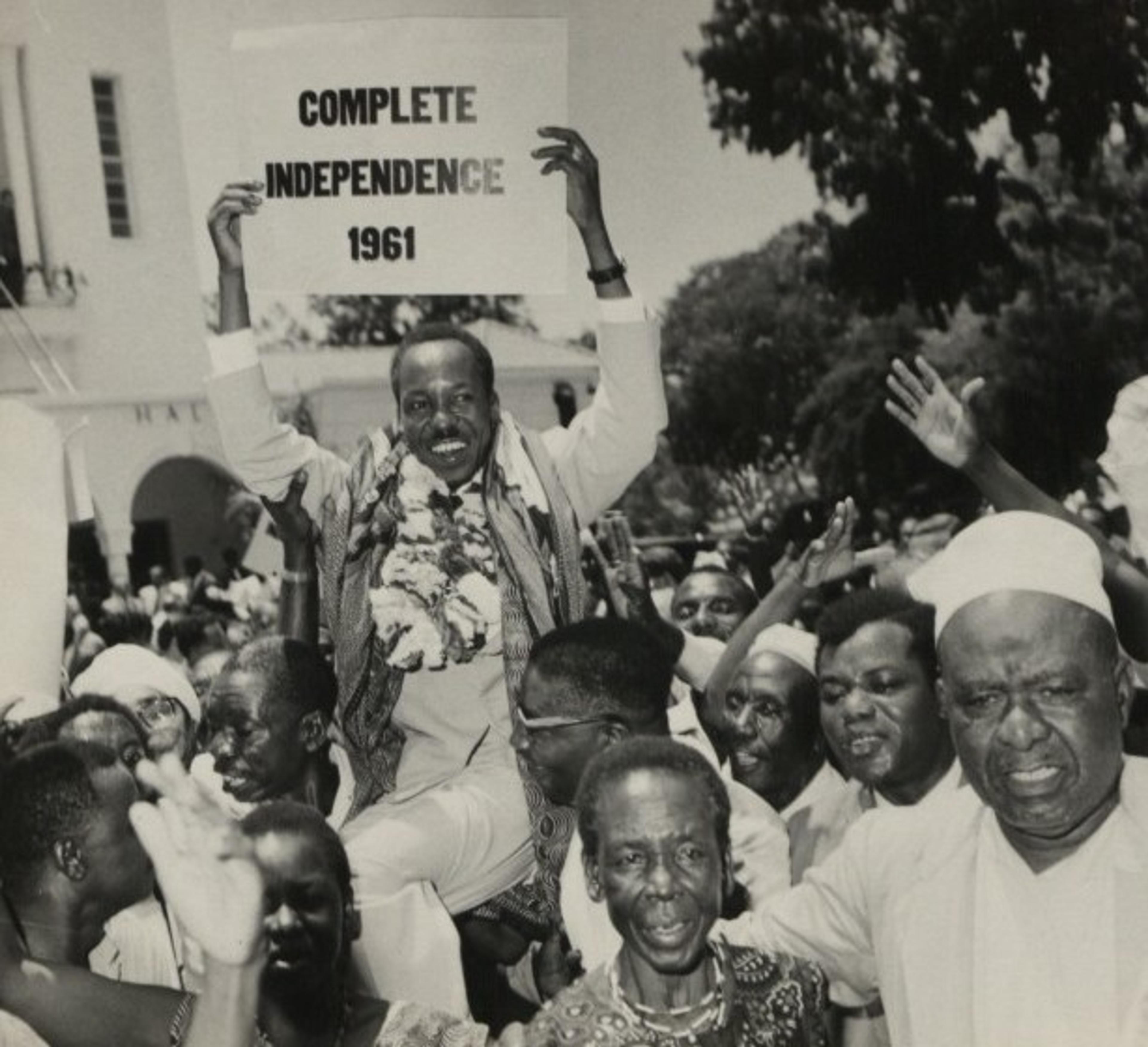

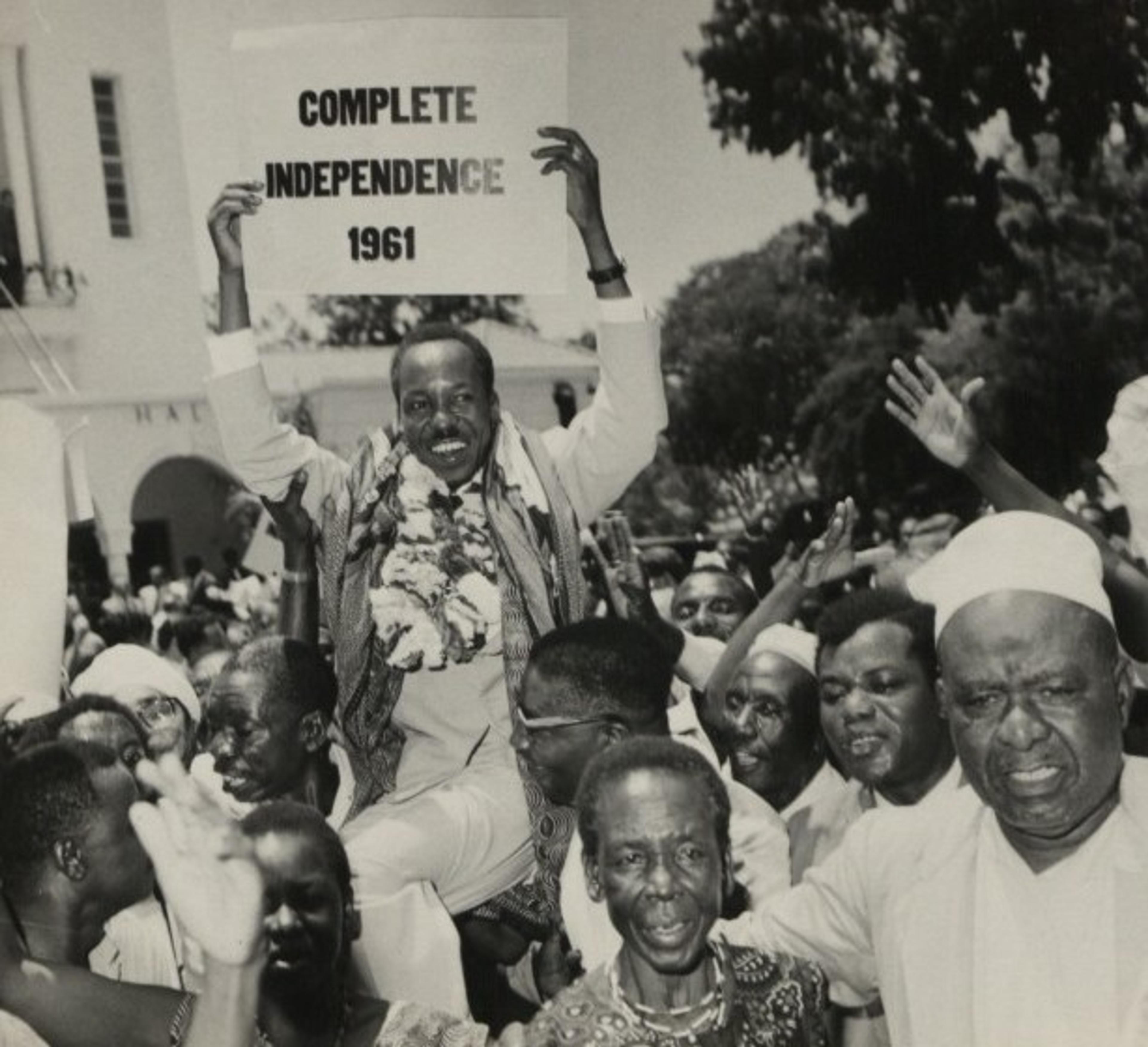

TANZANIA

December 9, 1961 / January 12, 1964, from the United Kingdom

Until 1961 and 1964, Tanganyika (mainland Tanzania) and Zanzibar were British colonies. Julius Nyerere led Tanganyika’s independence movement and was its first postcolonial leader, while Zanzibar briefly established a constitutional monarchy controlled by a minority Arab population. In 1964, thousands of Zanzibaris of Arab and Indian descent were killed or expelled after a popular uprising overthrew the Omani sultan Sayyid Saïd bin Sultan al-Busaidi, as Zanzibar was the location of his court. Soon after the upheaval, Tanganyika and Zanzibar merged to form the United Republic of Tanzania, though Zanzibar maintained some autonomy. Today, Tanzania is one the most ethnically and linguistically diverse countries in Africa.

1962

BURUNDI

July 1, 1962, from Belgium

Ruanda-Urundi’s (present-day Rwanda and Burundi) independence was led by a number of nationalist movements, including the Union for National Progress (UPRONA), established in 1958. As anticolonial nationalism spread in the Congo in the late 1950s, the Belgian government grew increasingly concerned. A surge of Burundian national pride following World War II prompted legislative elections in 1961, and the country gained independence the following year. However, ethnic tensions and violence complicated Burundi’s transition to independence. Belgian and earlier German colonial rulings attempted to racialize and categorize distinct groups, particularly the Hutu and Tutsi communities. Since independence, Burundi has been divided by coups, assassinations, and civil wars.

RWANDA

July 1, 1962, from Belgium

Belgium’s “divide and rule” strategy in Rwanda favored the Tutsi minority, much of whom represented the precolonial aristocratic class, while suppressing Hutu political participation. In 1933, the colonial administration issued I.D. cards categorizing individuals as Tutsi, Hutu, or Twa based on their appearance. Following independence in 1962, the country experienced coups, dictatorships, and civil unrest that further intensified these divisions. Tensions between the Hutu and Tutsi eventually led to a genocide in 1994 that killed nearly 800,000 people.

ALGERIA

July 5, 1962, from France

In 1954, the Algerian War of Independence began with the National Liberation Front’s (FLN) campaign of guerrilla warfare against occupying French forces. The conflict was marked by violence and war crimes. As it dragged on, France lost support from its citizens and allies. Devoid of political will, French Prime Minister Charles de Gaulle asserted Algeria’s right to self-determination in 1959. The Evian Accords, which was a set of peace treaties signed by France and the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic in Évian-les-Bains, France, ended the war and granted Algeria independence in 1962. Nevertheless, political instability, economic hardships, and continued violence characterized the aftermath of independence, including a period of civil war in the 1990s that killed thousands.

UGANDA

October 9, 1962, from the United Kingdom

After more than sixty years of British colonial rule, Uganda gained independence from Britain on October 9, 1962. Several rival political parties, including the Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) and the Kabaka Yekka (KY) party, fueled the nationalist movement for independence. However, ongoing ethnic, linguistic, and religious tensions complicated the transition to independence. Consequently, Uganda’s early years of independence resulted in political instability and violence, including the assassination of the country’s first prime minister, Benedicto Kiwanuka.

1963

KENYA

December 12, 1963, from the United Kingdom

Kenya gained its independence from Britain on December 12, 1963, after a protracted struggle against colonial rule since the late nineteenth century. In the wake of World War II, for which Kenya provided manpower and abundant resources, growing nationalist sentiment led to the formation of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) under the leadership of Jomo Kenyatta, who would become the country’s first president. KANU’s reform efforts were considered insufficient by many Kenyans and more militant groups emerged to take up the independence cause. Between 1952 and 1959, the Mau Mau led a violent resistance campaign against British authorities, which prompted colonial authorities to declare a state of emergency. By 1963, continued colonial administration of Kenya had become too costly.

1964

MALAWI

July 6, 1964, from the United Kingdom

From the late 1800s until 1953, Malawi, formerly known as Nyasaland, was a British protectorate, then part of the short-lived Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (also known as the Central African Federation). Bitter opposition to the Federation, coupled with a rise in postwar nationalism across the continent, led to civil unrest and decolonial resistance. Malawi’s independence movement was led by the Malawi Congress Party (MCP) under the leadership of Hastings Kamuzu Banda. After independence, Banda became the country’s first president and ruled Malawi for three decades as a totalitarian one-party state.

ZAMBIA

October 24, 1964, from the United Kingdom

Formerly known as Northern Rhodesia, Zambia was administered as a protectorate by the British South Africa Company, who viewed the region chiefly as a source of labor for its mines. In 1924, the British government assumed administration of Northern Rhodesia, which it would maintain for another four decades. After World War II, British politicians feared that Southern Rhodesia (today Zimbabwe) would fall under the sway of Afrikaner nationalists who had risen to power in South Africa. In 1953, the decision was made to join Northern Rhodesia, Southern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland (today Malawi) under the Central African Federation (CAF), which was met with growing nationalist opposition. By 1963, the Federation had dissolved, and in the following months the country gained independence from Britain. Although the early years of Zambian independence were prosperous, the nation quickly slid into one-party rule, which continued until 1991.

1965

GAMBIA

February 18, 1965, from the United Kingdom

The Gambia River, from which the country takes its name, cuts deep into the African continent, making it a coveted geographic feature for the European countries who sought to gain an advantage in the slave trade. It is estimated that more than three million people from the region were sold as slaves between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. Following years of territorial jockeying, Gambia was established as a British holding in the late nineteenth century during the Scramble for Africa, an imperial episode where Belgium, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Spain partitioned Africa into subsequent colonies. Following World War II, internal pressure for independence grew. On February 18, 1965, Gambia was granted independence within the British Commonwealth of Nations (the political association of former British colonies).

ZIMBABWE

November 11, 1965 / April 18, 1980, from the United Kingdom

In 1888, the British imperialist and mining magnate Cecil Rhodes received a concession of exclusive mining rights for the British South Africa Company (BSAC) from King Lobengula of the Ndebele peoples in Matabeleland. The following year, the BSAC was granted a royal charter for administration of the Matabeleland and its client states. In 1895, the BSAC formally renamed the territory “Rhodesia” after Rhodes imposed a violent, extractive regime. Although Rhodesia’s government, which comprised members of the white minority, unilaterally declared independence in 1965 in response to the British government’s “Wind of Change” approach to African independence (the empire’s final attempt at maintaining power in their African colonies), formal British occupation of the region did not cease until 1980, following a fifteen-year civil war.

1966

BOTSWANA

September 30, 1966, from the United Kingdom

The Bechuanaland Protectorate, known as Botswana from independence onward, was annexed and administered by Britain in 1885 to safeguard their existing colonies in southern Africa. When the Union of South Africa was formed in 1910, the Bechuanaland Protectorate was not among the British colonies incorporated. The region was instead used as a convenient appendage to its neighboring colonies, to which it provided migrant labor and rail routes, and was planned to eventually be incorporated into Rhodesia or South Africa. With the codification of apartheid in South Africa, this objective became unviable and Britain, pressured by growing nationalist sentiment, began to push the region toward self-governance. In 1966, Botswana officially gained independence from Britain but remained economically dependent for the first five years of its existence.

LESOTHO

October 4, 1966, from the United Kingdom

At the request of King Moshoeshoe I, Lesotho, known as Basutoland until independence, was made a protectorate by Queen Victoria in 1868, to prevent further invasions by Dutch and British colonists. In 1871, a year following Moshoeshoe I’s death, Basutoland’s administration was transferred to the British Cape Colony, which initiated efforts to undermine traditional leadership structures. Following World War II, Basutoland saw the emergence of nationalist parties who pressed for independence, granted by the British in 1966. In the succeeding years, Lesotho’s economy and political stability remained intimately tied with South Africa.

1968

MAURITIUS

March 12, 1968, from the United Kingdom

Mauritius was colonized by various European powers, including the Dutch, French, and British, with the latter holding control between 1810 and 1968. Following the abolition of slavery in 1835, the British began importing indentured labor from other regions of the empire, particularly India, to work on sugar plantations. Over the coming decades, resentment mounted between the majority Indo-Mauritian community and the Franco-Mauritian elites and plantation owners. Prior to independence, the country experienced significant social and political unrest, including trade union strikes and deadly race riots. By 1965, Britain had initiated a decolonial approach to its African holdings, and the following year, Mauritius became an independent state of the British Commonwealth of Nations (the political association of former British colonies). However, economic inequality and ethnic tensions persisted.

ESWATINI

September 6, 1968, from the United Kingdom

After the Second Boer War, a decolonial conflict between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the South African Republic and the Orange Free State), Swaziland (today Eswatini) was claimed as a British territory in 1903. Its land was partitioned between 1907 and 1910, with only 38 percent reserved for the Swazi population. However, Swaziland retained its monarch, under Sobhuza II, who reigned for more than sixty years and advocated for land restoration. In 1968, Swaziland gained independence from Britain as a constitutional monarchy. Five years later, Sobhuza II suspended the constitution and dissolved parliament, rendering Swaziland an absolute monarchy, which it remains today. In 2018, fifty years after independence, the nation’s name was changed to Eswatini, to reflect the Swazi name for the state.

EQUATORIAL GUINEA

October 12, 1968, from Spain

As much of the African continent gained independence in the 1960s, Spain decided to pursue partial decolonization in Equatorial Guinea in an effort to dissuade the rise of local independence movements. By 1967, however, growing internal nationalist fervor and pressure from the United Nations prompted Spain to hold a constitutional convention. The convention ended in a deadlock with Equatorial Guinean separatists and unionists divided primarily along ethnic lines. In 1968, Equatorial Guinea gained independence from Spain and Francisco Macías Nguema, whom Spanish Francoists had supported, was elected president in the country’s only fair and free election. The nation’s newfound independence was quickly overshadowed by an influx of refugees from the Nigerian Civil War and authoritarian rule.

1973

GUINEA-BISSAU

September 24, 1973, from Portugal

Guinea-Bissau was a Portuguese colony from the fifteenth century until its independence in 1973, although white Portuguese settlements were discouraged on the mainland unlike on nearby islands, such as Cape Verde. Beginning in the 1960s, the region’s leading nationalist group, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC), established a guerrilla campaign against Portuguese forces primarily on the mainland in Portuguese Guinea. Backed by communist nations, the PAIGC gained control of a large swath of territory and unilaterally declared independence in 1973 after more than a decade of fighting. After independence, the young nation added the name of its capital city, Bissau, to Guinea to avoid confusion with the former French colony of Guinea. Following independence, the country experienced profound political instability, including a one-year civil war between 1998 and 1999.

1975

MOZAMBIQUE

June 25, 1975, from Portugal

Mozambique’s struggle for independence began in the early 1960s, as self-determination movements spread across the African continent, with the formation of the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO). FRELIMO waged guerrilla war against Portuguese colonial rule, which had administered Mozambique for more than four centuries. The armed conflict lasted for over a decade, resulting in the deaths of thousands of Mozambicans and Portuguese soldiers. Mozambique became an independent nation in 1975 under FRELIMO control, but the country was soon swept into a fifteen-year civil war as opposition forces funded by Rhodesia and South Africa sought to overthrow the one-party regime.

CAPE VERDE

July 5, 1975, from Portugal

Positioned along key trade routes between Africa, Europe, and the Americas, Cape Verde had been claimed by the Portuguese since the fifteenth century, before which the islands had been uninhabited. A number of factors—famine, epidemics, and the rise of Pan-Africanism on the mainland—led to the Cape Verdean independence movement. In 1956, alongside other activists, Amílcar Cabral, a trained agricultural engineer, founded the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC). Quickly, the party became the basis of both Guinea’s and Cape Verde’s independence movements and eventually waged armed rebellions against the Portuguese in 1961. More than a decade later, PAIGC controlled much of Portuguese Guinea despite the presence of Portuguese troops. Portuguese Guinea declared independence in 1973, and two years later, Cape Verde was granted independence by the Portuguese.

COMOROS

July 6, 1975, from France

In 1975, following more than a century of French occupation and subsequent colonial rule, Comoros gained sovereignty and established itself as an independent republic. The country faced significant challenges in the following years, including political instability, a series of coups, and continued French administration of the island of Mayotte, whose population voted against independence.

SÃO TOMÉ AND PRÍNCIPE

July 12, 1975, from Portugal

Although Portugal had officially abolished slavery in 1876, forced labor by exiled Angolan and Mozambican “undesirables” remained intrinsic to the islands’ cocoa and coffee plantations until the mid-twentieth century. In the 1950s and 1960s, a small group of São Toméans opposed to Portuguese rule formed the Committee for the Liberation of São Tomé and Príncipe. It was not until 1975, a year after Portugal’s dictator, Marcelo Caetano, was overthrown, that São Tomé and Príncipe achieved independence.

ANGOLA

November 11, 1975, from Portugal

The territory that is now Angola was colonized by the Portuguese in 1484, when explorer Diogo Cão established a trading post at the mouth of the Congo River. Portuguese settlements and outposts were established along the Angolan coast, mainly for the purpose of enslaving and trading Indigenous Angolans, a practice that continued into the early nineteenth century. Even after abolition, colonial-era laws prohibiting Black Angolans from forming political parties or labor unions and requiring Black Angolan men to pay an imposto indígena (native tax) bolstered a system of unpaid, coerced labor. A rise in labor activism in 1960 shifted into a twelve-year war of independence that ended with the collapse of Portugal’s conservative and autocratic regime, Estado Novo (New State). Following independence in 1975, Angola became a one-party state rooted in Marxist-Leninist principles.

1976

WESTERN SAHARA

February 27, 1976, from Spain

Colonized by Spain from 1884 to 1976, Western Sahara has continued to seek independence from Morocco, which annexed the territory after Spain’s withdrawal. The Sahrawi-led Polisario Front, a nationalist liberation movement, declared the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) an independent state in 1976. Morocco, however, has annexed large parts of the country since 1975 and fought a war with the Polisario Front until a UN-brokered truce in 1991. Today, Morocco claims sovereignty over Western Sahara and controls about 80 percent of its territory, while the Polisario Front controls about 20 percent. A new round of fighting between Morocco and the Polisario Front broke out in November 2020.

SEYCHELLES

June 29, 1976, from the United Kingdom

While the islands of the Seychelles were known to Austronesian and Arab traders for centuries prior to European incursion, they remained uninhabited until colonization by Europeans beginning in the sixteenth century. The islands came under British control in 1794 and remained a colony until 1976, when it was granted independence. Seychelles remains a member of the British Commonwealth of Nations (the political association of former British colonies) and the least populated sovereign African nation.

1977

DJIBOUTI

June 27, 1977, from France

Present-day Djibouti was first established as French Somaliland. In 1958, a referendum was held to determine whether French Somaliland would remain a French territory or become an independent nation. Despite the failure of the first independence referendum, two subsequent referendums were held throughout the late 1960s and 1970s in response to inroads by armed liberation movements. The territory gained independence in 1977 and formally changed its name to Djibouti after 98 percent of its population voted to disengage from France. However, the country’s early years were marked by instability, culminating in a civil war beginning 1991 until 2000.

1990

NAMIBIA

March 21, 1990, from South Africa

Namibia was established as a German colony in 1884 under Chancellor Otto von Bismark to prevent further British encroachment on what was then known as German South West Africa. As German colonizers quickly set about realizing their vision of a white “new African Germany,” they seized land and property, and, between 1904 and 1908, committed a genocide against the Herero and Nama peoples. With the outbreak of World War I, the South African government, which aligned itself with the Allies, ordered its troops to invade German South West Africa. South Africa continued to administer the region until 1988, until it succumbed to years of guerrilla struggle by the South-West Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO). Free elections were held in 1989, and Namibia’s first president, Dr. Sam Nujoma, was sworn into office in 1990.

1991

ERITREA

May 24, 1991, from Ethiopia

After decades of successive Italian and British occupation, Eritrea formed a coalition with Ethiopia in 1952 despite largely mixed public sentiment. Six years later, a group of Eritreans covertly founded the Eritrean Liberation Movement to counter Ethiopia’s attempt at state centralization. In 1962, a decade after the Federation of Ethiopia and Eritrea was established, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia annexed Eritrea, breaching international law. The resulting Eritrean war of independence was subsequently waged against successive Ethiopian governments until May 1991, when a coalition of liberation groups regained control of the capital. International recognition of Eritrea’s independence was granted in 1993 when the nation was also admitted as a member state of the United Nations.

2011

SOUTH SUDAN

July 9, 2011, from Sudan

Following a brutal civil war, a referendum was held in southern Sudan from January 9 to 15, 2011, to determine whether it should remain part of Sudan or become an autonomous nation. More than 98 percent of the southern Sudanese population voted for independence. While Sudanese president Omar Bashir acknowledged the results of the referendum, South Sudan’s road to sovereignty has remained plagued by armed conflict, intercommunal violence, border disputes, and food insecurity.