Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern

1 of 11

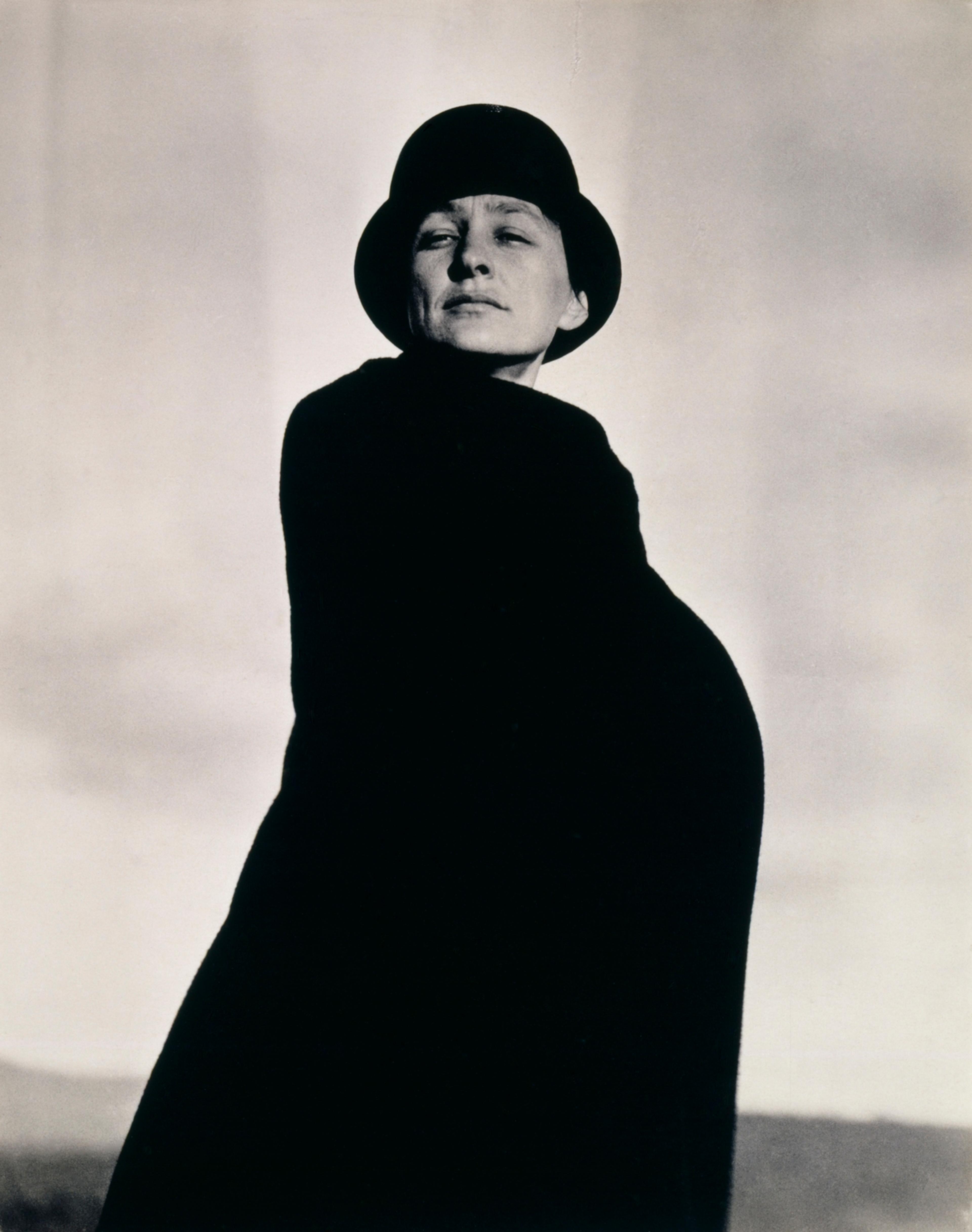

Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern takes a new look at how the renowned modernist artist proclaimed her progressive, independent lifestyle through a self-crafted public persona—including her clothing and the way she posed for the camera. The exhibition expands our understanding of O'Keeffe by focusing on her wardrobe, shown for the first time alongside key paintings and photographs. It confirms and explores her determination to be in charge of how the world understood her identity and artistic values.

In addition to selected paintings and items of clothing, the exhibition presents photographs of O’Keeffe and her homes by Alfred Stieglitz, Ansel Adams, Annie Leibovitz, Philippe Halsman, Yousuf Karsh, Cecil Beaton, Andy Warhol, Bruce Weber, Todd Webb, and others. It also includes works that entered the Brooklyn collection following O’Keeffe’s first-ever museum exhibition—held at the Brooklyn Museum in 1927.

The exhibition is organized in sections that run from her early years, when O’Keeffe crafted a signature style of dress that dispensed with ornamentation; to her years in New York, in the 1920s and 1930s, when a black-and-white palette dominated much of her art and dress; and to her later years in New Mexico, where her art and clothing changed in response to the surrounding colors of the Southwestern landscape. The final section explores the enormous role photography played in the artist’s reinvention of herself in the Southwest, when a younger generation of photographers visited her, solidifying her status as a pioneer of modernism and as a contemporary style icon.

Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern is organized by guest curator Wanda M. Corn, Robert and Ruth Halperin Professor Emerita in Art History, Stanford University, and coordinated by Lisa Small, Curator of European Painting and Sculpture, Brooklyn Museum.

Lead sponsorship for this exhibition is provided by the Calvin Klein Family Foundation. Generous support is also provided by Anne Klein, Bank of America, the Helene Zucker Seeman Memorial Exhibition Fund, Christie's, Almine Rech Gallery, and the Alturas Foundation. The accompanying book is supported by the Wyeth Foundation for American Art and the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Art Foundation and is published by the Brooklyn Museum in association with DelMonico Books • Prestel.

We are grateful to the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, whose collaborative participation made this exhibition possible.

Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern is part of A Year of Yes: Reimagining Feminism at the Brooklyn Museum, a yearlong series of exhibitions celebrating the 10th anniversary of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art.

Organizing department

Special Exhibition