The Many Shades of Ancient Egyptian Pigments

What does scientific analysis reveal about New Kingdom pigments in the Brooklyn Museum collection?

by Morgan E. Moroney

April 30, 2024

Ancient Egypt was flooded with color. Artists and craftspeople brightly embellished a variety of surfaces, including temple and palace walls, coffins, statues, and pottery. Although some of this vibrancy has faded over thousands of years, relatively rich examples of pigments and their traces still survive thanks to Egypt’s dry climate.

How, and with what, did ancient artists paint? A new installation in the Brooklyn Museum’s ancient Egyptian art galleries provided a great opportunity to answer this question. Before the installation was put on public display, our Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern Art team and Conservation department analyzed each object, allowing us to explore Egyptian pigments from their raw state to their final, colorful application.

The objects we studied, which date to the New Kingdom (ca. 1539–1075 B.C.E.), include four samples of raw pigments, a paintbrush, a palette made out of a bivalve shell, four fragments of painted pottery, a preserved painted vessel, and statuary. The artists’ tools have never before been exhibited, and none of these newly installed objects had been scientifically analyzed.

While investigating and identifying pigment types is not new in museum studies or Egyptology, our team’s analyses expanded our body of knowledge of Egyptian pigments. Utilizing noninvasive techniques including MBI (Multiband Imaging) and pXRF (portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy), the Museum’s Conservation Lab was able to identify, to various degrees, the chemical makeup of pigments. These studies were all performed without destructive sampling, a process that involves the removal, and sometimes destruction, of a tiny amount of material from an object. MBI involves examining objects under various wavelengths of light, such as ultraviolet (UV) and infrared (IR), while pXRF detects the major, minor, and trace elements on the surface of an object.

In ancient Egypt, pigments were sourced from minerals such as iron, copper, and cobalt, which were mixed with liquid binders to create colorful paints. Identifying pigments can yield a wealth of information about ancient objects, including details on sourcing and trade routes. Minerals such as ochres, sourced from earth and clay, and carbon-based black were usually accessible to artisans in Egypt, but some pigments had to be imported into the Nile Valley from the Eastern and Western Deserts and Oases, or even farther away.

Additionally, pigments can illuminate aspects of artistic technologies, techniques, and innovations during various periods. Knowing the composition of pigments also helps conservators determine the best way to preserve and protect objects.

Uncovering pigments: An investigation

The raw pigments above were excavated at the New Kingdom site of Tell el-Amarna, also called Amarna, in the 1930s. Amarna, a city built by the king Akhenaten, was abandoned shortly after his death around 1336 B.C.E. The city’s palaces, temples, houses, workshops, and tombs are a rich source for understanding the lives of both royal and non-elite individuals. However, as with most early 20th-century excavations, the archaeological methods and standards at Amarna in the 1930s were lacking compared to today’s, and the exact place(s) of discovery of these lumps of pigment was not recorded.

These pigments entered the Brooklyn Museum collection in December 1934, acquired through a subscription service with the Egyptian Exploration Fund (today the Egyptian Exploration Society). The Museum helped fund the excavation work at Amarna in the 1930s and, as was customary at the time, received objects from the dig when the finds were divided between Egypt and the excavators and sponsors.

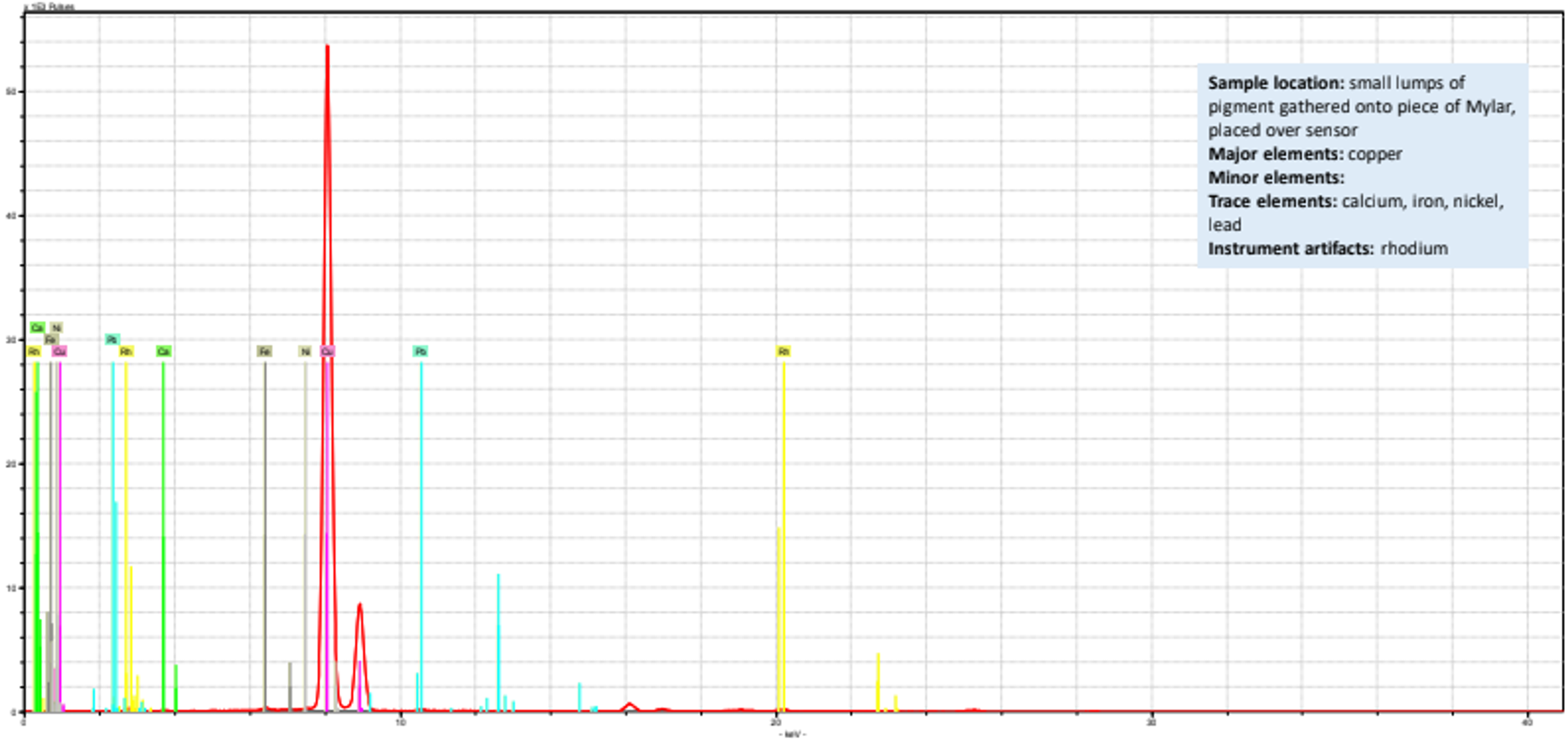

The red, blue-green, yellow, and blue lumps were analyzed and interpreted by Michael Galardi, Assistant Objects Conservator, before they went on view this year. pXRF revealed that the red and yellow pigments both have iron as their major element. The red is derived from a hydrated iron oxide, such as hematite, and the yellow is from a hydrated iron oxide, such as goethite. This data suggests that they are both ochres, a relatively common pigment derived from soil or clay.

The bright-blue pigment is more unusual. Its major element is copper, from which most ancient blue and green pigments are derived. However, the trace amounts of calcium, iron, nickel, and lead, and the absence of phosphorus, aluminum, and silicon, suggest it might be azurite, a blue copper mineral with known sources in the Sinai Peninsula and Egypt’s Eastern Desert.

Egyptian blue, often called Egyptian blue frit, is the world’s oldest synthetic pigment, its earliest uses dating back to the third millennium B.C.E. Frits are mixtures of fired quartz, lime, and alkali flux; they are similar to glass, but are heated to a lower temperature to be fused rather than to flow. Egyptian blue frit includes copper, which creates its rich color. Egyptian blue was thought to imitate lapis lazuli, the dark-blue stone that was imported to Egypt from a source in present-day Afghanistan. Egyptian blue could be powdered down and combined with binders to create blue pigments. It also fluoresces when examined under VIL (visible-induced infrared luminescence), making it easy to identify through multiband imaging.

The large piece of blue-green frit pigment was initially thought to be Egyptian blue. However, Katherine McFarlin, a graduate intern in the Conservation department, noticed it did not fully fluoresce under VIL, and the pXRF reading suggested it was most likely another manmade pigment called Egyptian green. This copper-based frit was meant to capture the color of a turquoise stone and could be ground down to make paint.

Along with the pigments, we analyzed a vessel fragment (above left). This sherd was purchased in the late 19th century in Egypt, but it is possible that it was made at Akhenaten’s city Amarna. Egyptian kings had several names, and these were usually enclosed within ovals called cartouches. This fragment includes the partial remains of three of Akhenaten’s cartouches.

This piece was once part of a complete vessel formed by mixing Egyptian blue with a binder, pressing the paste into a mold, and firing. The Egyptian blue frit used to form this vessel would have been a paler blue than our sample of Egyptian green frit (above right).

The bivalve shell above, which served as a palette, includes blue, red, brown, and gray pigments. Assistant Objects Conservator Celeste Mahoney analyzed its shades and concluded the blue is Egyptian blue and the red is an ochre and umber, another iron-based pigment. The other two paints appear to be mixes of pigments and liquid binders. It is currently uncertain what the binders—often animal or plant gum—consisted of, but based on VIL analysis, it is clear that Egyptian blue was mixed with the gray-green and brown paints, probably to create various tones.

The palette and brush above were most likely not originally a pair; a finer brush was probably used with the shell. Unlike the shell, the brush does not have any traces of Egyptian blue pigment, reinforcing that they were not used together. They do, however, exemplify tools utilized by artists and craftspeople throughout Egyptian history. Below, a scene from Queen Meresankh III’s Old Kingdom tomb depicts an artist holding a shell palette and painting a statue head, which resembles the later, colorful example of a woman’s painted head.

Closely examining this woman’s head demonstrates how scientific analyses can sometimes create more questions than answers. The statue might have been coated in a lime plaster in sections before being painted, which was not uncommon for certain stone surfaces in Egypt. Identifying the pigments proved challenging. It was difficult to discern whether paint had been added in modern times or if some readings, like zinc and strontium, were simply part of the stone. The woman’s hair was painted with an ochre, and carbon black was probably used for her eyes; however, traces of lead were detected in her pupil. This black might have been mimicking galena, a lead sulfide used for kohl in Egyptian eye makeup. Sections of the red pigment on her headband and lips contain minor peaks of mercury, which may mean it is vermillion or a modern restoration.

Reading pottery for clues

While statues were decorated throughout Egyptian history, pottery was mainly painted during the Predynastic period (ca. 4400–3100 B.C.E.) and the New Kingdom (ca. 1539–1075 B.C.E.). New Kingdom pottery, our focus here, was painted for both aesthetic and functional reasons.

If they could not afford a fine stone vessel, an ancient Egyptian might have had a clay pot painted to imitate stone, like the one above. These types of jars were also valued.

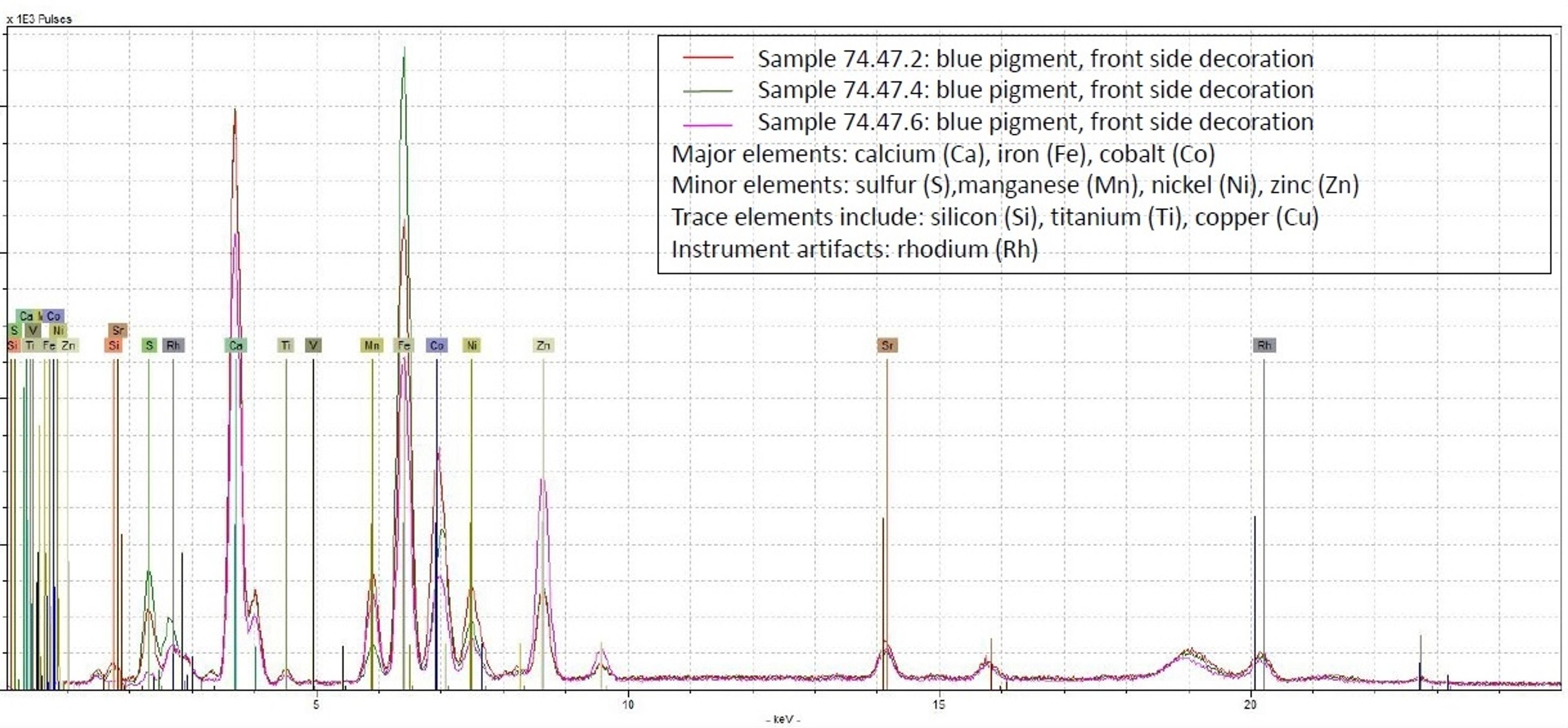

Another type of pottery, known as New Kingdom blue-painted ware, features vibrant blue paint that Egyptian artists invented using pigments often derived from cobalt and alum. The known sources for cobalt are in the Kharga and Dakhla Oases, far out in Egypt’s Western Desert. These vessels also incorporated black and red pigments in their decoration. The three blue-painted ware fragments above are possibly from Malkata, a palace of Amunhotep III, Akhenaten’s father. They are decorated with patterns meant to imitate flowers and garlands strung on jars.

As shown above, these painted fragments do not fluoresce like the Egyptian blue frit fragment under VIL.

Project Objects Conservator Angela Leersnyder performed pXRF analysis on the blue-painted ware sherds and confirmed they were painted with cobalt blue.

Over time, the naturalistic motifs seen on blue-painted ware sometimes became more abstract, as on this painted jar. Although less intricate than the three fragments, this intact jar was also decorated with a cobalt-based pigment, and it was probably produced in a workshop alongside more finely executed vessels.

Pigments: Ancient and today

Although these New Kingdom objects are a small sample, the Brooklyn Museum’s conservation team was able to identify an array of pigments. New Kingdom artists were using various types of blues and greens such as cobalt, Egyptian blue, Egyptian green, and possibly azurite; browns, yellows, and reds from ochre and possibly umber and vermillion; and black from carbon. These pigments were sourced from around the Nile and imported from the deserts and beyond.

Analysis of the pigments led to fascinating insights. The confirmation of cobalt-based blue pigment on the blue-painted ware sherds and the painted jar further supports the theory that these types of vessels were made in royal workshops, even when styles were simplified. The identification of the Egyptian green frit is particularly exciting, as Egyptian green is less well known than Egyptian blue; its analysis adds to the research and story of Egyptian green. The variety of pigments on the small bivalve shell reveal how painters might have used a large number of pigments at once, and mixing helped create even more hues. Finally, the Conservation Lab’s identification of the pigments informed its decisions regarding the best preservation and treatment techniques for ancient Egyptian objects. All these discoveries would not have been possible without scientific testing.

Such revelations make us eager to continue our research. Future testing of these and other pigments could include analyses not currently available in the Brooklyn Museum’s lab, such as SEM-EDS (scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy) and XRD (X-ray diffraction). This could lead to more definite conclusions about the pigments, such as whether those on the limestone head are modern or ancient and definitive confirmation of the azurite pigment. Ancient colors might fade, but the modern and close analysis of pigments can still reveal a wealth of information.

Morgan E. Moroney is Assistant Curator for Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern Art (ECANEA). This project included the work of Yekaterina Barbash, Curator, ECANEA; Rachel Aronin, Research Assistant, ECANEA; Kathy Zurek-Doule, Supervising Museum Instructor/Curatorial Associate, ECANEA; and Conservators Lisa Bruno, Kate Tyler, Michael Galardi, Celeste Mahoney, Angela Leersnyder, Maribel Cosme-Vitagliani, and Katherine McFarlin.